Create swaths of colour to fire up your spring garden

Forget-me-nots and other spring ground covers for the woodland garden

Forget-me-nots combine with other native plants including wild geranium to form a carpet surrounding this highly textured tree trunk in a nearby woodland.

Forget-me-nots and other flowering ground covers for the woodland

Few spring-blooming flowers easier to grow than Forget-me-nots, or Myosotis, if you like to impress your friends with Latin names.

These charming, low-growing spring flowers, that are well known for their tiny, delicate blue blossoms with yellow centres – though they can also be pink or white – want nothing more than cool, moist conditions to spread throughout your garden. And woodland gardens usually have plenty of these conditions to offer.

I think I started with a packet or two thrown in an out-of-the-way spot in the woodland garden several years ago. Today, these usually biennial plants put on a lovely show in the early spring just when the garden is waking up.

Last spring, during my extensive exploration of the woodland around our home, I stumbled up large swaths of these lovely little spring bloomers. If Mother Nature taught me anything, She showed me that growing Forget-me-nots for impact was not for the timid.

A fawn surrounded by Forget-me-nots and other native plants in our spring woodland garden.

The larger the swaths the better. In fact, I first noticed these flowers on my walks in the woods from a distance. One morning, a blue mist far down the path rose up from the spring greens and caught my eye. (see image below).

Little did I know that it was the beginning of Forget-me-not season in our little woodland. The plants seemed to be everywhere – circling trees, edging forest paths, weaving their way through the forest and around other native plants.

Forget-me-nots are well-suited for woodland gardens due to their ability to naturalize and spread, creating a carpet of color under trees and shrubs. Their early spring blooms attract pollinators, supporting local wildlife and contributing to the garden's ecological balance.

I stumble upon this exquisite clutch of Forget-me-nots growing on a fallen, moss-covered tree stump in a nearby woodland. Duplicating the scene in your own garden should not be difficult with these easy-to-grow plants.

When planting forget-me-nots en masse, you can achieve a stunning visual impact, creating a lush carpet of blooms that enhances the overall aesthetic appeal of the garden. This planting technique not only adds a cohesive look but also mimics the way these plants grow in the wild, forming beautiful clusters that blend seamlessly with the surrounding vegetation.

These plants require minimal care but benefit from occasional watering during dry spells and deadheading to prolong blooming. By incorporating forget-me-nots into your woodland garden, you not only elevate its beauty but also support local wildlife and promote biodiversity, making them a perfect choice for any nature enthusiast.

In my walk through the woods, there were few single plants popping up here and there. These were communities of Forget-me-nots working together, and the effect was truly memorable.

A blue mist rises out of the forest floor in spring reminding us that the Forget-me-nots are in bloom.

We need to bring some of this abundance into our gardens, even if it is just for a brief time in spring.

Grow theses plants around trees to highlight them in spring. Put them in large swaths so that from a distance their tiny flowers form a beautiful blue mist arising from a corner of our garden (see above image), and tuck them along pathways so they guide your way to a favourite destination.

Along the way, you will be joined by early pollinators.

A little background: Forget-me-nots are from the genus of flowering plants in the family Boraginaceae. In the Northern Hemisphere, they are known as forget-me-nots or scorpion grasses and are the official flower of both Alaska and Daisiand, Sweden.

The name comes from Ancient Greek and means "mouse's ear", which the foliage is thought to resemble.

Along a pathway

Spread seeds along a pathway to add interest in quiet areas in the garden and help to lead the way.

Their foliage is alternate, and their roots are generally diffuse. They typically flower in spring or soon after the melting of snow in alpine regions.

If nature teaches us anything, it is to be bold with our plantings. As a spring ground cover, Forget-Me-Nots can really bring a smile to our faces.

The flower is native to Europe, Asia, and North America.

Unfortunately these little flowers are not long-lived and, as they say, death is not their finest hour. That’s when they grow leggy, dry up, and are often beset by powdery mildew in their waning days. To ensure a good crop the following year, however, it’s important to resist the temptation to pull them up, before they finish setting seeds.

If living with their ugly dead stems is too much, intermingle lots of perennials and annuals where they are growing to help cover up their unsightly dead stems.

These hardy, self-seeding plants thrive in cool, moist conditions, often used to edge beds with spring bulbs like tulips, but some varieties can become invasive, so deadheading is key if you don't want them to spread. far and wide.

They're tough, attract pollinators, and offer a lovely texture in woodland, rock, or container gardens

Forget-me-nots prefer cool weather and moist soil. They grow best in lightly shaded areas, but in wet soil they can take full sun. In hot-summer climates, they need shade and extra moisture to survive.

Forget-me-nots are easy to start from seeds. Just scatter seeds in a shady garden area at the end of summer. The seedlings will have plenty of time to settle in before winter. You can also start seeds indoors, but, why bother. Keep it simple and distribute seed generously in areas of the garden. Your efforts will eventually be rewarded.

How they got their name

Legend has it that a French knight walking along a river with his lady and a clutch of flowers fell into the current. Before sinking into the river forever, he threw the flowers to his lady, shouting don't “forget me.” Not sure if it’s true but there is a lesson here. When walking along a river with heavy armour on, leave the flowers be. In fact, we shouldn’t be picking any flowers in nature. Lesson learned the hard way.

Back to the plants: they are really a short-lived perennial best grown as an annual. However, it can also be grown as a biennial by planting seed in the ground in mid-summer for bloom the following year.

Of course, Forget-me-nots are just one of many woodland plants to consider as ground covers in our gardens.

Trilliums are another flowering native that can make an outstanding spring ground cover when planted en masse.

Combine other Native Ground Covers with Forget-me-nots

Native plants play a crucial role in garden ecosystems, promoting biodiversity and supporting local wildlife. When considering native ground covers for your woodland garden, trilliums, wild geranium and Canada anemones are excellent options and can work well growing among the Forget-me-nots.

Trilliums, known for their three-petaled flowers, bring a touch of elegance to woodland settings. These plants not only add beauty but also provide essential habitat and food sources for insects and small mammals. When planting trilliums, ensure they are placed in well-draining soil with dappled sunlight to encourage healthy growth. Regular watering and mulching can help maintain their vibrant blooms throughout the season.

Canada anemones, with their delicate white flowers, offer a graceful alternative for ground cover. These plants thrive in moist, shady areas, making them ideal for woodland gardens. Canada anemones also attract pollinators and contribute to the overall ecosystem balance. To cultivate Canada anemones successfully, provide adequate moisture and space them out to allow for their spreading nature while keeping them in check to prevent overcrowding.

Consider planting Canada Anemone in your garden to create a carpet of white in spring.

By incorporating trilliums and Canada anemones into your woodland garden, you not only enhance its visual appeal but also contribute to the preservation of local flora and fauna, creating a harmonious and thriving natural environment.

Concluding the exploration of native ground covers in woodland gardens, it is evident that incorporating plants like forget-me-nots and other native species offers a multitude of benefits. These ground covers not only enhance the visual appeal of your garden but also provide crucial support for local wildlife, promoting biodiversity and ecosystem balance. By planting these native species en masse, you can create a thriving habitat for insects, birds, and mammals, contributing to the preservation of local flora and fauna.

Luminar Neo and Lensbaby combine for the ultimate in creativity

Adding a creative touch with Luminar Neo and Lensbaby lenses.

Our spring dogwood proved to be the ideal subject for the Lensbaby Composer and Sweet 50mm lens with a macro filter attached. Combine this soft, ethereal image with two subtle textures using Luminar Neo’s layering and blend modes and the existing photograph is turned into a painterly image that I’m betting most would be proud to call their own.

Textures add painterly effects to ethereal images

Ansel Adams once said you don’t “take a photograph, you make a photograph.”

Back then, Adams used the traditional darkroom to create magnificent Black and White images of the natural world, often times spending days in the darkroom “making” these images.

Today, the traditional darkroom has been replaced with the digital darkroom, turning the concept of “making” images rather than just “taking” them accessible to every photographer who chooses to explore their creativity and take their photography to new heights.

In this post, I am going to explore how, combining the inherent creativity built into every Lensbaby lens with the creative tools available in Luminar Neo, can change how you approach garden and flower photography as well as portraiture and landscapes.

• Go to the bottom of this post for the latest HOLIDAY offering from Luminar Neo

In case readers are unaware of the magical qualities of Luminar Neo post processing software and Lensbaby’s creative line of photographic lenses, let’s take a moment to familiarize ourselves with these creative photography tools.

While the first image of the dogwood flower is rather subtle, this image of paperbark maple leaves in fall shows what can be achieved with heavier textures applied through Luminar Neo’s layering and blending modules. The original image was taken with the Lensbaby 2.0 and sweet 50mm lens.

Luminar Neo is a photo editing software package that combines ease of use with the power of Ai to assist photographers, who may have been hesitant to dive into more complex photo editing software in the past, to embrace the ease and convenience of a more simplified, yet powerful, editing program.

Lensbaby is a lens manufacturer that embraces and encourages photographers to push creativity by offering lenses with unique characteristics that create elegant, soft-focus effects, beautiful colour blending and soft ethereal results that enhance almost any image, especially in the garden, with flowers and portraits.

In the final days leading up to Christmas, Luminar Neo is offering a special “creative” Advent Calendar package just in time for photographers to give themselves a special gift for the season.

The lowest price is available now, but once the doors officially open, the cost will range from $119 to $159 depending on if you are a new or existing user.

The Advent Calendar includes 12 unique surprises, each hidden behind a daily window. Photographers can discover a new gift every day, such as:

🔸 Luminar license

🔸 Marketplace items (Skies, bundles and more)

🔸 X-membership subscription

🔸 Educational courses

There are different surprises depending on the Luminar Neo package you choose or currently own.

Check out the information at the end of this post for details on the special creative and educational packages.

This image was taken with the Lensbaby Composer and sweet 50. It was then brought into Luminar Neo where a number of textures were applied creating a more painterly effect. One of the textures was also used to add the lovely, subtle pink tone to the image.

Adding textures to existing images is rather simple with Luminar Neo’s intuitive photo editing program. It’s as simple as dropping a textured image on top of your main image and then choosing from a host of blend modes from a drop-down menu. Once the texture is applies and the blend mode chosen, it is up to the photographer to decide if they want to go farther using masks or a host of other editing modules within Luminar Neo.

One of my new favourite modules is Luminar Neo’s incredible “Light Depth” module that is capable of transforming flat, boring images into beautifully lit, three-dimensional images. Check out my earlier post here, for more on using the Light Depth module in Luminar Neo.

These Northern Sea Oat grasses photographed with a Lensbaby 2.0 was given added interest by using a Luminar Neo built-in golden dust texture effect. You can create your own textures, find free ones on line or purchase more professional textures through Luminar Neo. Their latest creative package might just include some of their professionally produced creative tools.

If you are interested in exploring Lensbaby lenses further, you can check prices here (Amazon.com) or here (KEH used camera exchange.) If you are interested in exploring Lensbaby lenses further, check out the offering of books available through Alibris used books here.

My earlier posts on Luminar Neo

Adding textures, manipulating lighting, or even repairing old family photos are just a few of the incredible bonus features offered by Luminar Neo’s comprehensive editing software. For more of my posts on the benefits of exploring Luminar Neo, I encourage you to check out the following posts.

• Exploring Luminar Neo mobile for your phone: click here.

• Exploring Luminar’s incredible photo restoration module: Click here.

• Can Luminar Neo act as your only photo editing program. Click here

Subtle textures were added to this macro image of a Hydrangea blossom taken with the Lensbaby composer fitted with a Lensbaby macro filter.

Of course, garden flowers are not the only subject for Lensbaby lenses and Luminar Neo textured effects. Below is an image taken recently of our new flat Coated retreiver, Colby. This image was taken with the Lensbaby Velvet 56. The Velvet series of lenses are capable of truly beautiful results with an ethereal glow that is magnified depending on the f-stop used (from quite sharp at f5.6 through f16 and getting softer from F5.6 through to F2.

Two B&W textures were added to the original image to maintain the overall B&W, painterly effect.

The image below and the above images represent just a few of the creative approaches available to photographers using special effect lenses and/or filters, and combining them with the creative effects available through Luminar Neo. Please explore the links provided for my earlier posts on Luminar Neo and be sure to click below to check out all of the special deals on creative assets, tools and educational resource materials Luminar Neo is adding for their “creative advent calendar.”

Our rescue Flat-Coated Retriever with his baseball stuffy taken with the Lensbaby Velvet 56 with two textures added for a painterly effect.

Luminar Neo’s holiday calendar of gifts explained

From December 13th to 24th, open a new surprise every day and discover creative tools, content, and inspiration worth more than $1000.

The calendar can also be gifted to friends, family, or photography enthusiasts, making it a thoughtful and creative holiday present.

Here’s what all the excitement is about. Unlock your treats every day leading up to the big day.

Calendar Timeline:

December 10: Presale begins with lower prices

December 13–24: Daily windows open (one per day)

December 16–25: Calendar available at full price

Going mobile with Luminar Neo

Luminar Neo’s powerful photo editing package goes mobile.

Luminar Neo goes mobile

A black dog in snow: The perfect example of why we need the power of a post processing photo program on our phones. Colby, our flat-coated retriever, loves the snow. Unfortunately, getting properly exposed photographs of him playing in the snow on our phones is impossible. With the help of Luminar Neo mobile app, pictured here, I was able to white the snow and lift the details in his jet-black fur, as well as brighten his eyes using Luminar Neo’s mobile app. I also cropped the image to make Colby larger in the Frame and use the erase module to take out some distracting plants in the upper left corner of the image. (See below for the original image.)

If you are like most of us, our phones are an integral part of capturing favourite memories.

Unfortunately, most of the images sit on our phones until we either get a new phone or delete them to save space. Sure, a fraction of them might make it to instagram, Facebook or sent via email to friends and family.

It’s rare, however, that these images are given the attention they deserve. It’s even rarer that they ever get an edit to fix problems and realize their full potential. Most are taken, forgotten and eventually deleted never to be seen again.

Smartphone failure

Our smartphone cameras can by very good at capturing difficult subjects but a black dog in the snow is not one of them. This “straight-out-of-the-camera image is the perfect example of why we need a powerful photo post processing program to rescue images prior to posting them online.

Throw away memories that are never printed and easily forgotten.

Luminar Neo is looking to change all that with their mobile app that packs much of their photo editing power into your phone. If that’s not enough, the folks at Luminar Neo are making transferring images from your phone to your laptop or desktop Luminar Neo post processing program as quick and easy as a few simple clicks.

• If you are an existing user to Luminar Neo, click here for more details.

• If you are a new user to Luminar Neo, click here for more details.

Do phone images even need editing?

You might say ‘my phone is capable of taking great images and don’t need to be edited.’

In many instances, images produced by your smartphone are very good. However, I can honestly say that most images can be improved with a quick edit, and many can be transformed with editing prior to publishing.

Colby in the snow after post processing with Luminar Neo.

If, for instance, your instagram account is important to you, taking a few minutes to quickly edit your images is time well spent.

For example, If you are taking images in unusual conditions, such as at the beach with white sand, or in winter with snow, or directly into bright sun, you will need to edit the images before posting. If you are taking images is poorly lit areas, using your phone’s flash or maybe you need to remove distracting elements. In all these cases, you will need the capabilities of a powerful post processing program.

That’s where the Luminar Neo Mobile app goes into action.

Lighten the shadows to bring out detail in the backlit image, turn that blueish snow into the crisp white you remember. Crop it, add some warmth, improve skin tones and even turn to a little Ai magic to remove distractions in the image.

And, that’s not all. Many of the features on the full desktop program are available on the mobile version, including Luminar’s transformative “Light depth” module. For more on this outstanding light manipulation editing module, check out my earlier post here.

For more on Luminar Neo’s Holiday gift for photographers, check out my post here.

Finally, if you want your favourite smartphone images on your laptop or desktop for further post processing, transferring your mobile images to your laptop or desktop Luminar Neo program is as simple as a few quick clicks. All of the edits you made on the mobile app are transferred to your desktop ready for you to further refine the image.

The folks at Luminar Neo have taken huge strides in combining the power of our smartphones with the power of their ai-based post processing software to put the magic of Luminar Neo literally at our fingertips.

And they have slashed prices this holiday season to make Luminar Neo the perfect gift to give to yourself or your favourite photographer.

What you get and pricing packages

You might be surprised just how much processing power you get for a more than reasonable price. Luminar Neo’s Black Friday offers are live with discounts of up to 77% — the perfect moment to get the full Luminar Neo Ecosystem.

Here are some of the pricing details: Please use the click here to get the discounts through my affiliate with Luminar Neo.

Prices for new users: Click here for more details

Luminar Neo Desktop Perpetual: $99

Luminar Neo Cross-device Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile): $139

Luminar Neo Max Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile + Spaces): $159

Prices for existing users of Luminar Neo: Click here for more details.

Upgrade Pass: $49

Ecosystem Pass: $69

Please use the two links above to get more information or to make a purchase. By using these affiliate links, I receive a small contribution at no extra cost to you for making the purchase.

Luminar Neo will take your photography to new heights

Luminar Neo post processing software is the simpler way to create outstanding images.

Cherry blossoms image created with the assistance of Luminar Neo’s post processing tool.

Simplify post processing to a few simple clicks

If there is one tool that has transformed my photography more than anything else in the last year, it has been the introduction of Luminar Neo’s photo editing program to my post processing toolbox.

Now, it’s available for up to 77 per cent off an already very reasonable cost.

By simplifying the whole process of editing my digital images down to merely a few simple clicks, the photo editing software has made post processing not only a real joy, but a way for me to discover new, and exciting approaches to photography.

And, when I want to take my images to a whole new level, Luminar Neo’s extensive editing tools offer all the capabilities that more serious amateurs or professionals would want in a post processing package.

Add their most recent additions to an already extensive list of tools and post-processing modules, and it’s probably fair to say that Luminar Neo is not only the new kid on the block, but it managed to take the best of what’s around, simplify it and add its own unique creative editing modules to put this photo editing software in a league all its own.

Click here for pricing and details if you are a new user of Luminar Neo

Click here for pricing and details if you are an existing user of Luminar Neo.

Luminar Neo is also not resting on its laurels. They tell me that in the coming weeks they will also be introducing the beta of their AI Assistant, a powerful new tool arriving in Luminar Neo before the end of the year.

Fall leaves shot with a Lensbaby lens and post processed with Luminar Neo post-processing photo software.

Light depth module

By far, Luminar Neo’s new “Light Depth” module is so transformative that it alone makes the program worth purchasing. The ability to change the light in your digital images to highlight areas of the scene from one with flat light, into one with a three-dimensional look, is game changing. Add to that, the ability to control the warmth and coolness of the scene both near and far – all with a few simple clicks – and it’s hard to not get excited about the possibilities.

Click here for my complete post showing the incredible results you can get from Luminar Neo’s Light Depth module.

A prized family photograph of my parents and relatives with famed Ink Spots lead singer Bill Kenny in B&W restored.

The same image colorized with one click by the power of Luminar Neo’s restoration module.

Restoring old photos is so simple

In its latest release Luminar Neo has made professional photo restoration and colour conversion as simple as one click. And the results are literally astounding. There is no more need to pay professional photo restorers to bring back your family photos, it’s all built into the new version of this Ukraine-based post processing photo program.

Click here for my complete post showing the transformative results you can get from Luminar Neo’s new Restoration module.

Luminar Neo offers users with their own Space to share their best images or family vacations with friends and family without the need for expensive websites.

Now you can get your own Space to show off your photos

No need for a fancy and expensive website, now you can get your own space to show friends and family your best images. As part of Luminar Neo’s newest release, purchasers can get their own “space” where they can show off their favourite photos or vacation pictures with friends and family without the expense of creating their own website.

Check out two spaces I recently created on Luminar Neo’s new “Spaces”. Our European vacation here and fall in the backyard here and for a look at a few of the images I restored using Luminar Neo’s “Restoration” module, click here.

More posts on Luminar Neo

All of this and much more is available with Luminar Neo’s latest release just in time for the holiday season. For my of my posts on Luminar Neo, check out the posts below.

What you get and pricing packages

You might be surprised just how much processing power you get for a more than reasonable price. Luminar Neo’s Black Friday offers are live with discounts of up to 77% — the perfect moment to get the full Luminar Neo Ecosystem.

Here are some of the pricing details: Please use the click here to get the discounts through my affiliate with Luminar Neo.

Prices for new uses: Click here

Luminar Neo Desktop Perpetual: $99

Luminar Neo Cross-device Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile): $139

Luminar Neo Max Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile + Spaces): $159

Prices for existing users of Luminar Neo:

Upgrade Pass: $49

Ecosystem Pass: $69

A gift for our backyard wildlife

Creating backyard habitat for owls, bats and bees is one of the greatest gifts you can give this holiday season.

It didn’t take long for this little screech owl to discover the Owl box we put up for her. She has now spent the last two winters in our yard.

This is the perfect year to let family, friends and relatives know that helping others during the holiday season is the ultimate gift. It may be nothing more than giving to a food shelter or offering a helping hand to a local family in need. Maybe donating to agencies helping war-torn countries like Ukraine.

These gestures can make all the difference during the holdiday season.

But don’t forget our backyard friends who will also appreciate a little helping hand. Reports are calling for some serious winter weather in most of Canada and parts of the United States as well as throughout Europe. That means keeping our feeders full will go a long way to easing any hardships local wildlife may face this winter.

Even better, why not consider adding specialized houses, not only to attract wildlife, but to help them through the cold winter months.

Several years ago I installed a screech owl house on one of our old pine trees and for the past two years we have had a screech owl spend the winter in our yard. Such a blessing to sit inside on a cold winter’s night and hear our little owl calling out, his big eyes peering out from the warmth of his home.

I have recently teamed up with Buy 2, Get 1 FREE! " target="_blank">Big Bat Box to offer readers excellent deals this holiday season starting on Black Friday and running through to December 7th. Although the company started out making outstanding Bat Boxes for our winged mosquito munchers, they now offer an assortment of bat, owl and bee boxes that would make outstanding gifts for nature lovers.

For my post on attracting owls click here. For my post on the importance of attracting bats to your yard, click here.

And to make it even better, Buy 2, Get 1 FREE! " target="_blank">Big Bat Box has a special deal available where you can buy 2 and get the third free. What a great way to cover three gifts at once. Or, you might just want to keep one of the houses for your own yard.

If that wasn’t enough, Big Bat Box is a Ukraine-based company. So, by supporting their efforts to help wildlife, you are also helping to support Ukraine as they fight for their survival against Russian aggression.

There are several styles and sizes to choose from in bat and owl houses.

Focus on street images for more memorable vacation photos

Focus on street photography for better vacation images.

Under a bridge along the pathway back to the river cruise ship, I noticed this musician entertaining the passersby. Most paid no attention to his presence, so I turned my camera on him to take advantage of both the graffiti and the lovely texture of the wall behind him. Although originally shot in colour, the RAW image was converted to B&W for a more fitting “street scene.”

We’ve all seen them, smiling faces standing like statues in front of tourist hot spots surrounded by hundreds of others waiting to get the exact same photo.

Sitting through photo after photo of “Here’s us in front of …..” get’s a little tiring for friends and family, but include some more “interesting” images and you might just have a very captive audience.

Don’t get me wrong, there’s a place for these images among your vacation snaps. After all, what would a European vacation be without a shot in front of the magnificent cathedral, the impressive fountain or the incredible view of the Alps. Nothing says “I was there” better than a snapshot at the scene.

But don’t forget to get your creative juices flowing by experimenting with more memorable images that capture the true experience of going to an unfamiliar place. Take the time to embrace the real culture of the area, roam some of the backstreets and bring home some truly memorable images of a once-in-a-lifetime vacation.

I was walking some backstreets in Heidelberg Germany looking for interesting images when I spotted this young girl walking toward me. As she walked past, I turned to capture her confidently walking down the cobblestone street past bikes heading to “who knows where” but with the confidence and sense of purpose that made me take notice. For the purpose of this “street photography” post, I converted the image to B&W, but her pink sweater and faded blue jeans and backdrop of pastel houses makes the scene as good in colour as it is in BW. (See the colour version below.)

That’s exactly what I did during a recent two-week European vacation that started and ended in Switzerland with stops in picturesque towns and cities in, The Netherlands, France and Germany.

While other passengers on the river cruise were entertained by the guide explaining the historical significance of certain tourist hot spots, I wandered off in search of more interesting images on side streets, at cafes and through shop windows.

The following is a small sampling of some of the “street” images I was able to capture, with explanations of why I was attracted to the scenes.

While my wife shopped in this well-known German Christmas store, I stayed outside looking for interested images. This young woman decorating a store window caught my eye and I shot several images of her arranging elements in the window. Shooting through windows is a common “street shooting” theme, but being able to photograph a worker decorating the window for Christmas was just too good to pass up.

Outdoor patios are such an important part of the culture in most European cities that it’s only natural to try to capture a taste of it. This waitress was setting up for lunch making capturing her coming through the doorway simply a matter of patience.

Bicyclists are an important part of the European culture. Walking the backstreets allowed me to capture this image, a quintessential European scene.

The iconic bike street scene. I was particularly attracted to the simplicity of the scene and the monochromatic look.

Another bike image. The shape of the bike attracted my attention as well as being able combine the three elements to complete the picture. The reflection in the windows also adds to the scene.

Look for small details

Again, wandering down the side streets, I stumbled upon a florist with a permanent four-legged friend.

Sometimes a scene presents itself and all you have to do is wait for the right subject to pass through it. This fellow looking at his phone walking away from a scooter was to good to ignore.

An iconic scene of an outdoor cafe in Germany. Waiting for the right moment adds to the simplicity of the scene. Moments before the image was taken, tourists milled about which would have turned the image into a touristy snapshot.

Searching for Simplicity

Finding simplicity in a touristy town is not always easy but with a little patience and a lot of luck, it’s possible. I was able to keep a very low profile by photographing with a Pentax Q miniature camera rather than a much larger DSLR camera and lens.

Pretty in Pink

This is the colour version of the image higher in the post. I love the soft pastel colours of the young girl’s sweater and jeans and the backdrop of coloured homes.

Rustic doorway

Our tour group stopped at a location to use the washrooms so I wandered around and found this old doorway complete with graffiti. The flowers at bottom right contrasts nicely with the vintage door.

This image was photographed in the same location as the BW image of the man and scooter above. I thought the woman’s red pants picked up on the red of the Lindt chocolate in the window and works better in colour than it would in BW.

Another outdoor cafe scene that captures the essence of a European city.

I noticed this well-dressed woman walking to the town centre earlier and came across her again people watching on a park bench. By moving around, I was able to add a little humour to the image by combining this colourfully dressed mannequin with the stylish woman.

I could not resist photographing this well-dressed gentlemen is his German attire.

Finally, I loved the vibrant colours of this woman’s clothing right down to her shoes and how her focus is trained on the beautiful pastries in the window of the highly acclaimed Cafe Gundel.

Embracing the beauty of the fall woodland garden

Some of my favourite plants for the best late fall colours in our garden captured with the original Lensbaby Composer lens.

The native grass Northern Sea Oats is a favourite of mine to photograph in fall. The lovely warm colours include beiges and muted purples. The lovely arc of the branches add to the effect and the small zone of sharpness from the Lensbaby adds to the delicateness of the overall image. Northern Sea Oats is an important food source for birds throughout the winter months. Last winter, they proved to be a favourite food source for our wild turkeys that visited on a daily basis.

Focus on plants for best fall colour

Full fall colour can be so fleeting.

If you’re not paying attention, all those beautiful reds, yellows and burnt oranges disappear into mounds of dried, crunchy leaves on the garden floor.

And that’s okay. The leaves carpeting the woodland floor provide a home for overwintering insects and their future offspring, as well as foraging birds looking to supplement their diet of seeds and berries.

Too many of us choose to stay inside at this time of year thinking the garden is all tucked in for the season. Experiencing late fall in the woodland, however, can be an extremely satisfying experience. Just breathing in the earthy aromas and the cool autumn air is a real joy. Add a hot chocolate or a large mug of coffee and your best four-legged friend at your side, and it’s hard not to appreciate our change of seasons.

Even in early November there are still flowers remaining on our Hydrangeas. These warm pinkish/purple tones give way to paper-thin beige flowers later in fall and through the winter months. Even as the last remaining colours fade, the plants continue to be impressive. The soft, ethereal look that the Lensbaby Composer lens provided here creates a lovely, delicate late fall image.

Now, if experiencing late fall in the woodland garden is a real joy, capturing beautiful fall images takes the enjoyment to an all new level.

I experienced that enjoyment this week (early November) when I decided to pull out the Lensbaby Composer lens to give it a much-needed workout to capture the delicate tones of the late fall woodland garden.

The Lensbaby Composer lens. Notice how the lens swivels on the ball socket. This gives the photographer the ability to move the focus point around the image.

For those who may not know about the Lensbaby line of lenses (Amazon link), you can check out their informative website here. If you are looking for a great deal on a large selection of Lensbaby lenses and accessories, be sure to check out the used options on MPB.com

In a nutshell, the minds behind Lensbaby, unlike most lens manufacturers, are not concerned about achieving extreme sharpness throughout the image. In fact, their focus is on creating soft, ethereal images where the photographer takes control of narrow bands of sharpness while the surrounding areas of the image is allowed to go soft. Depending on the f-stop chosen, the depth of sharpness increases or narrows.

Strong fall colours can still be found in the garden in November. Here, a trio of leaves from our Japanese Maple (Moonglow) show off their fall colour. It’s hard to imagine these leaves earlier in the year sporting their vibrant spring chartreuse colouring. This rather expensive, slow-growing Japanese Maple performs from early spring through late fall and is certainly one to consider for your woodland garden, especially if it is on the smaller side. Notice how the Lensbaby Composer’s sharpness is so restricted that only half the leaf in the front is sharp while the remaining half is rather soft.

Lensbabies are ideal lenses for creative flower photography as well as portraiture, but they have their place in landscape images especially fall landscapes.

The Lensbaby Composer is a completely manual lens and requires a little work getting the focus the way you want it. I like to use a combination of a sturdy tripod and a Hoodman Loop to nail the narrow band of focus. The Hoodman Loop also helps me see the image on the back of the LCD screen, especially in bright lighting conditions.

The following are just a few images of my favourite fall-colour woodland garden plants taken this fall with the Lensbaby Composer.

More information about the subject is included below each image. If you are looking to add fall colour to your garden, you could do worse than putting these plants on your list of purchases in the spring. Of course, there are many other plants that offer bold fall colour to our landscapes, but these plants are sure winners in our garden.

Even in November, there is still plenty of colour in the garden. These American Viburnum leaves can be showstoppers in late fall. Although the birds and other garden wildlife already devoured the bright red berries, the leaves continue to put on quite the show. If you are looking to add late fall colour, this native, berry-producing shrub that wildlife love is an excellent choice.

If you are looking to add a punch of purple to your garden, consider the beautyberry bush with its outstanding late fall crop of purple, pearl-like berries that provide backyard wildlife with another winter food source. Not only are the abundant berries an exciting addition to the fall garden, the leaves, with their purple veining, add their own hit of purple to the garden’s pallete.

Another Hydrangea shows off its mauve fall colour and small berries.

The delicate branch of another Japanese Maple is captured here with the Lensbaby Composer. Notice how the focus of the lens is not to capture the scene in ultimate sharpness, but to create a softness that is particularly appropriate for this scene. The out-of-focus background, with hints of pastel greens, add to the overall mood. This is the more common Japanese Bloodgood Maple. One of its fall features is that it drops almost all its leaves in a single day and creates a carpet of bright red leaves as a natural ground cover.

Don’t forget to look on the forest floor for lovely fall colour at this time of year. Larger maples, oaks and tulip trees provide fall colour in both the upper canopy and later when they drop to the forest floor. I captured this lovely native Sycamore tree leaf among the ferns and other leaves. Whether you choose to just experience the fall garden, or capture it with your camera, the potential to squeeze just a little more out of fall in the garden can be a rewarding experience.

How can we forget the colours of our Dogwoods in fall? This Cornus Florida leaf is another standout in the late fall garden adding to the trees’ year-round interest beginning in spring with its incredible flower bracts, through early fall with its red berries and rounding out the year with its spectacular fall colours. The native dogwoods as a group are an excellent addition to any fall woodland garden.

One last image I wanted to show readers. Although it was not taken in the garden, it shows the interesting effects possible with the Lensbaby Composer in more of a landscape image. Lensbaby chose to feature my image on its website to illustrate how the Lensbaby can take a more traditional image and help the photographer obtain a more creative one.

MPB.com is an excellent place to either trade in your previously used photo equipment or purchase dependable used camera gear, whether it’s your dream camera or lens. For a great selection of Lensbaby lenses from MPB, click here.

Image shows a Japanese Maple covered in a late fall snowfall. This image was not taken with the Lensbaby but I could not resist adding to it.

Luminar Neo brings treasured family memories back to life

Restoring vintage family photos has never been easier with Luminar Neo’s new Ai restoration module.

Luminar Neo not only took this outstanding vintage black and white image of my mother, father and aunts posing with our cousin Audrey and her husband, acclaimed singer of the Ink Spots, Bill Kenny, but modernized it with an extraordinary colour rendition using the “Full” module in the post processing photo program. (see BW image below.)

Restoring, colourizing vintage photos

Not long ago, fixing old family photographs involved bringing them to professional photo retouchers and paying a week’s salary to have a handful of them restored.

Those days are gone thanks to a new, incredibly impressive new feature in this fall’s Luminar Neo release.

With a single click of your mouse, you can transform a faded, scratched, blemished old black and white photograph into a perfect reproduction of the original Black and White version.

And that is just the beginning.

The simplicity of the “restore” module is almost too good to believe.

Rediscover treasured photos

This prized family group portrait of the acclaimed lead singer for the Ink Spots Bill Kenny and wife Aubrey pictured here with my mother (2nd left and father far right) at a club in Halifax Nova Scotia. Luminar Neo was able to repair any scratches and blemishes on this BW image with the simple click of a single button. Another button colourized it (see above).

Restore module is the essence of simplicity

In fact, there are just three buttons to choose from to transform your vintage images: “Full” which repairs scratches, blemishes and colourizes the image to modern standards; “Colour” which simply colourizes the image without removing scratches and blemishes for a more authentic Lomography look; and “Scratches” which leaves the image either in its original BW or colour state and simply removes any scratches or blemishes on the photograph.

It’s so simple and effective that it is difficult for me to go into much more detail than – choose what you want to do and press the appropriate button.

If you are interested in trying Luminar Neo, please consider using my affiliate link HERE to purchase the program. By doing so, I receive a small payout that does not affect your purchase price.

This is the restoration module in Lumina Neo. Simply drop the image into the box and choose Full, Color of Scratches. Then hit the Restore button. The final image will show up in a separate folder within Luminar Neo called “Restoration.”

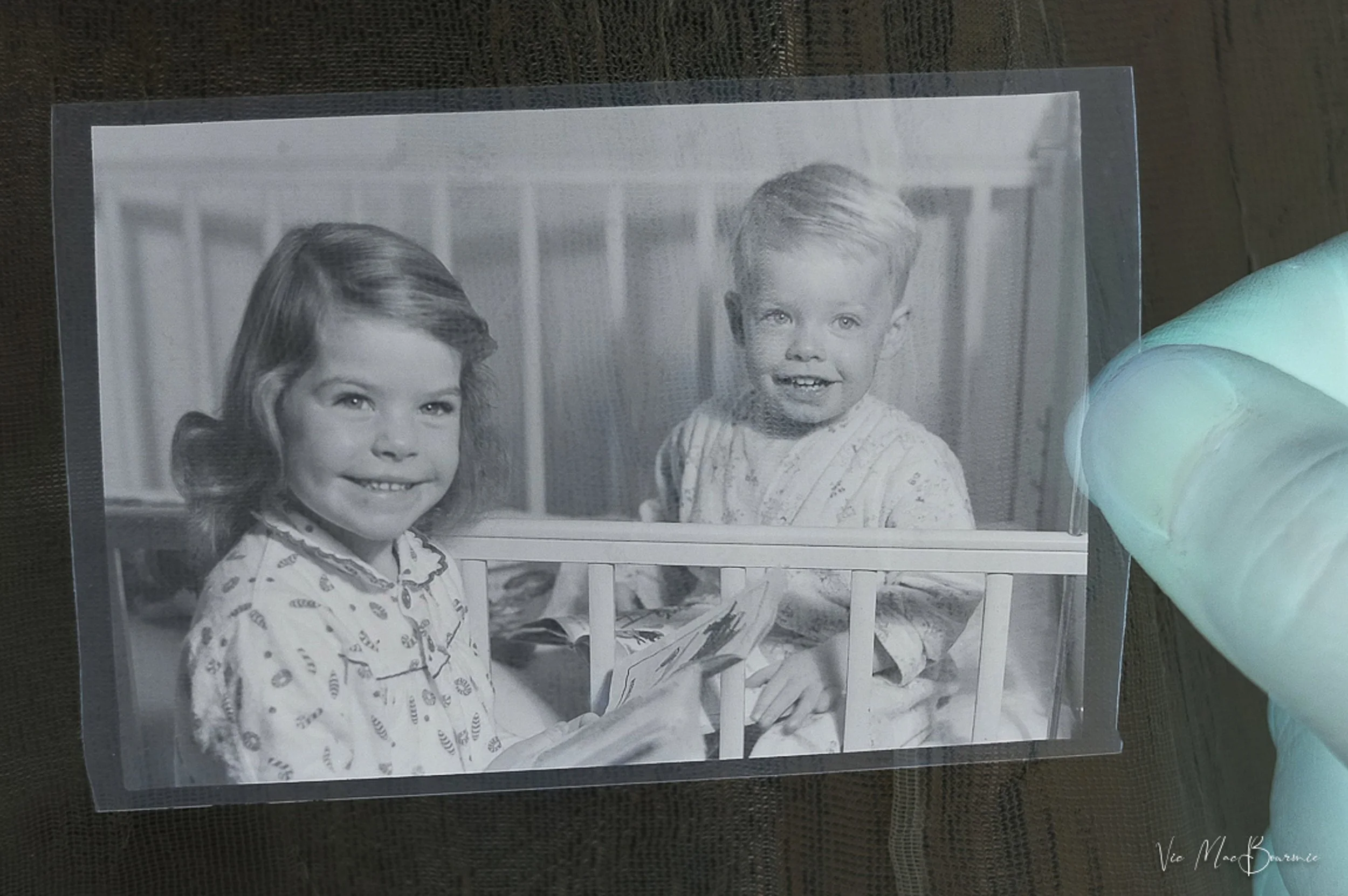

My sister and I on large format negative inverted.

The same image of my sister and I ran through the full module which colourized the photograph as well as adding some interesting vintage touches. Running the images through the module can result in slightly different results, which makes the entire process even more exciting to see the results.

Obviously, you will have to have a way to get the old images into Luminar Neo. I choose to use a flatbed scanner, but you could easily take digital pictures with your phone or, even better, a digital camera with the ability to take close-up images.

Once the images are on your computer or phone, import them into Luminar Neo, drop them into the restoration box, choose the appropriate button – either Full, Colour or Scratches – and Luminar Neo will drop the finished photo into a separate folder named restoration.

It’s as simple as that. The following are just a few examples’s of what the “restoration” Ai module can do in just a minute or two.

For more before-and-after images, check out my new “Spaces” gallery from Luminar Neo here.

The original BW image prior to any post processing.

A “Full” colorized version of the vintage image.

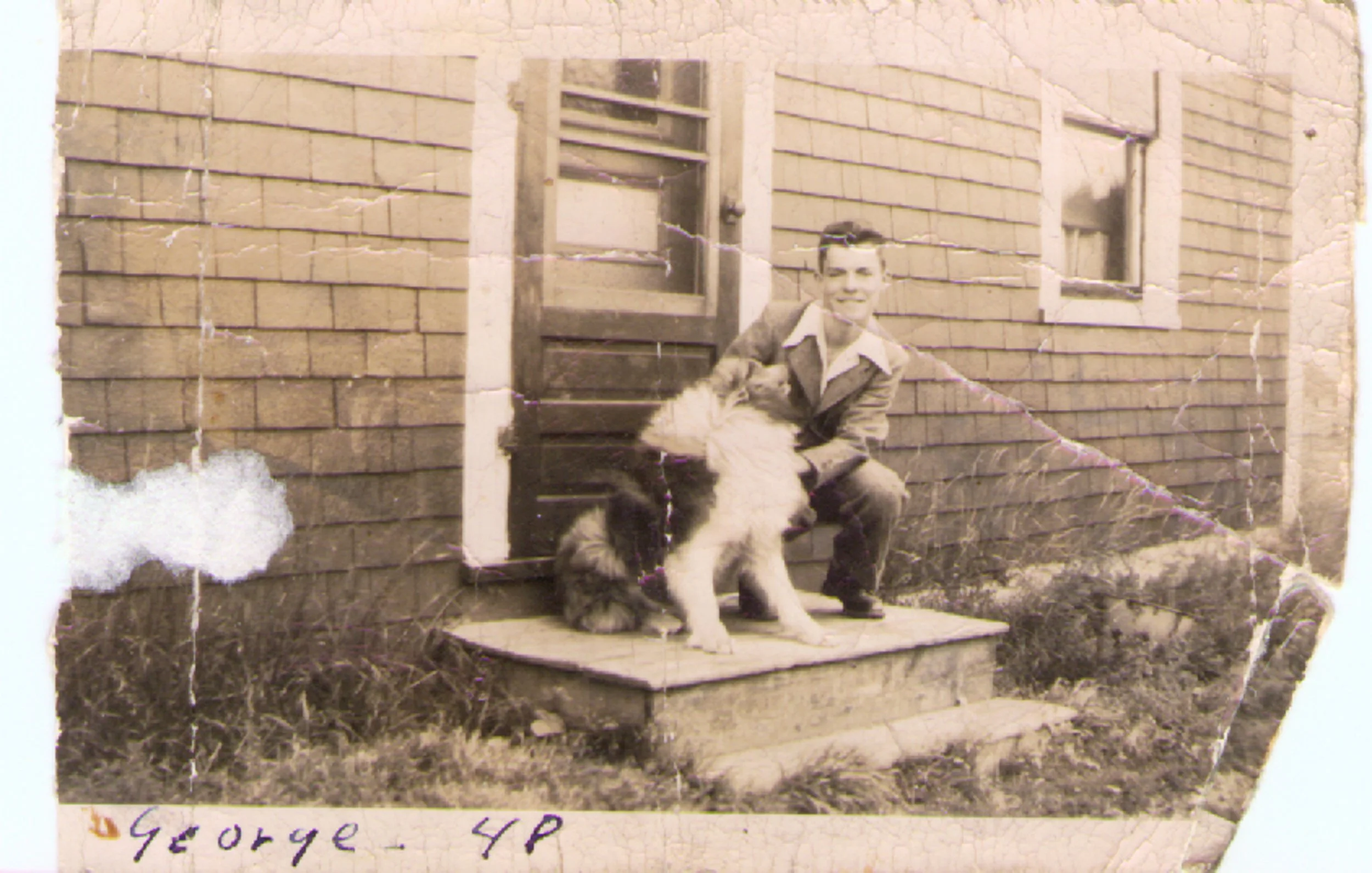

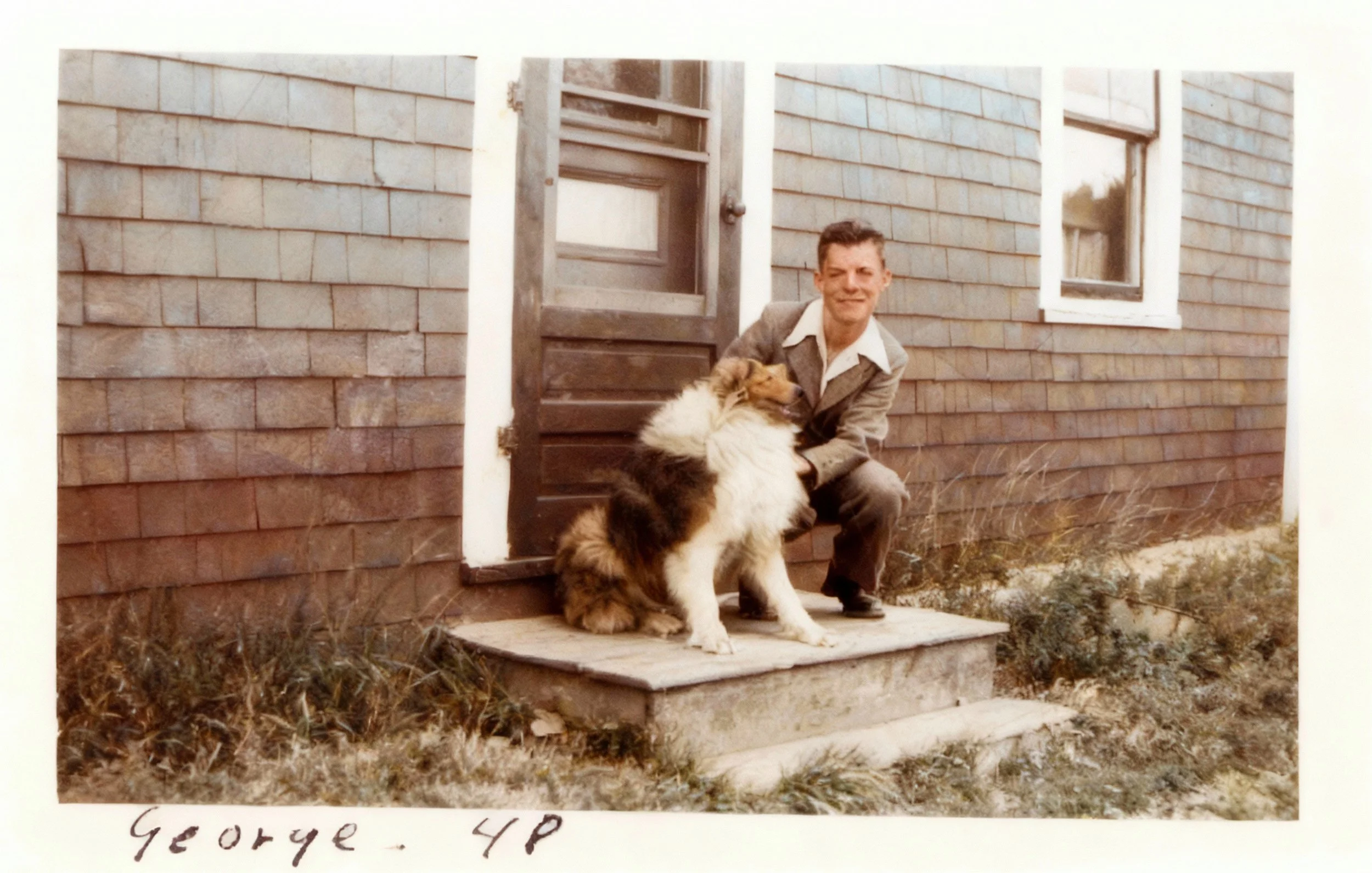

The following is a good example of what the Luminar Neo “Restoration” module can do for heavily compromised images by not only restoring them by removing scratches and even missing parts of the image, to colourizing them to create authentic-looking images.

The following shows the original scan, a repaired scan and the final colourized version.

This is the original, untouched image of my uncle and his dog.

The same image ran through the restore module – a single click of a button in Luminar Neo.

The final restored and colourized image. Note that the ai changed the dog’s profile slightly.

If you are interested in trying Luminar Neo, please consider using my affiliate link HERE to purchase the program. By doing so, I receive a small payout that does not affect your purchase price.

If you are a new user to Luminar Neo, use this link.

If you are a current user of the program, use this link

Prices below: Black Friday is Coming:

Dates: October 24 - December 1

Discounts: Up to -75% on the Luminar Neo Ecosystem - the best prices of the year!

Prices for new uses:

Luminar Neo Desktop Perpetual: $99

Luminar Neo Cross-device Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile): $139

Luminar Neo Max Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile + Spaces): $159

Luminar Neo takes lighting to another level

Luminar Neo has changed the way we see light forever.

This woodland fall scene is an example of how Luminar Neo’s new light-depth module can transform a relatively flat image into a more three-dimensional one. The smaller inset photo below shows the original image.

Transform your fall images with newest tool

If photography is all about light, Luminar Neo may have just rewrote the future of post processing.

I can’t think of a single feature, besides Ai erase and replacement, that has excited me quite as much as Luminar’s new Light Depth module.

Subtle but sweet

The change in the photos is subtle unless you know where to look. The light in the first image is moved forward to create a strong foreground band of light that lights up the brush in the front as well as the tree trunks. The effect helps to give the entire image added depth.

This module can take a good image to greatness in seconds and create a completely controllable, three-dimensional-lighting effect that is unmatched by any other post processing program I have experienced.

And, if used carefully, it can be beautifully subtle, or, not so subtle at all but always believable.

It’s just one of the new features unleashed in Luminar Neo’s fall package that includes a host of outstanding additions from improved mobile/desktop compatibility, to a highly useful photo restoration module that also has the potential of changing the way photo restoration is done both for amateur and professional photographers. And all of this added to an already impressive package of features for a very low price. For pricing details, go to the end of this post.

For more of my images showing Luminar Neo’s new Light Depth module as well as their free galleries for members, click here.

Although the Beech tree was also “lit up” in the original image, by manipulating the light depth module settings, I was able to darken the background and create a much more dramatic image. In addition, I used Luminar Neo’s light ray module to emphasize sunrays coming in from the right side of the frame.

If these three additions were not enough to convince anyone sitting on the fence about diving into this Ukraine-based post-processing photography package, this extremely innovative company is adding personal galleries to their repertoire of features to allow Luminar Neo users to share their best work with family, friends, clients and other Luminar Neo users.

I’ll be making separate posts on these features in the future.

If you are interested in trying Luminar Neo, please consider using my affiliate link HERE to purchase the program. By doing so, I receive a small payout that does not affect your purchase price.

Added drama

The before-and-after shows the dramatic difference created by darkening the background by shifting the light in the depth module. Luminar Neo’s new feature helps to create a more three-dimensional look.

Luminar Neo Light Depth module: Painting with light

But back to the reason for this post: The incredible “Light Depth” module.

I am not going to try to explain how this thing works, but suffice it to say that it’s an example of how ai can transform your images in subtle, yet incredibly useful ways. The module does not add anything to your image, it simply helps the photographer to manipulate the lighting in the scene.

How it all works in real life

In short, the module allows you to control the light “near” the front of the image, and the light toward the back of the image. Sliders give the photographer control of the amount of light, the warmth of the light and the softness all the while providing a map of the scene to help the user control the light in quite fine detail.

The module’s secret sauce can transform your images from flat, evenly lit scenes into more three-dimensional images with much more depth.

Below are a few before-and-after images I took just recently of fall colours in the woodland around our home showing the results. I try to keep most of the edits subtle, but you can choose the amount and quality of light you feel is needed to create the images you are trying to achieve.

This spectacular old oak tree set against the colours of fall literally stopped me in my tracks. Pulling the oak tree away from the background proved to be relatively simple in Luminar Neo’s Light depth module. without it, the scene (see below) is rather flat and the beautiful oak tree dissolves somewhat into the overall scene.

The rather flat lighting seen here, does not put the beautiful old oak tree in its best light.

Although I loved the birch trees and the leaf-covered pathway in this image, the lighting in the original proved to be very flat. Luminar Neo’s Light Depth module created the ray of light across the pathway and into the tree canopy as well as adding a subtle light to the birch trees. The result is a more three-dimensional image with a whole lot more interest. This result probably could have been achieved with other post processing software, but certainly not this easily and with this amount of control.

Adding depth to flat lighting

The before picture is rather flat in comparison to the edited version. Of particular note is the absence of the ray of light that cuts across the leaf-covered pathway in the edited version,.

Luminar Neo’s new tool will help transform your fall images

Fall is a spectacular time to get out and capture the rich colours all around us. However, no matter how good the colour is, lighting plays an important role in the success of your images. Getting out at different times of the day including early morning and late afternoon improves our chances of capturing great light, but there are no guarantees.

Luminar Neo’s new Light Depth module helps photographers improve their chances of creating images with interesting light by giving them control of the light in post processing. The results can be subtle, yet very effective.

If you are interested in more of my posts on using Luminar Neo, check out the following links:

• Luminar Neo in the woodland.

Fall colour and birch trees using Luminar Neo’s Light Depth feature.

If you want to see more of my fall images using Luminar Neo’s Light Depth module, be sure to check out my new Fall 2025 Gallery brought to you by Luminar Neo as part of their fall rollout of features. Check it out here.

If you are considering adding Luminar Neo to your existing photo processing packages such as Lightroom and Photoshop, it should be noted that the programs work seamlessly together. You can even open Luminar Neo from within Lightroom.

If you are wondering about the cost of this exceptional photo editing program, let me share some information and a couple of images that might help convince you to make the jump.

This image taken with a Lensbaby and the Light Depth module creates an interesting effect that I think works nicely.

If you are interested in trying Luminar Neo, please consider using my affiliate link HERE to purchase the program. By doing so, I receive a small payout that does not affect your purchase price.

If you are a new user to Luminar Neo, use this link.

If you are a current user of the program, use this link

Prices below: Black Friday is Coming:

Dates: October 24 - December 1

Discounts: Up to -75% on the Luminar Neo Ecosystem - the best prices of the year!

Prices for new uses:

Luminar Neo Desktop Perpetual: $99

Luminar Neo Cross-device Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile): $139

Luminar Neo Max Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile + Spaces): $159

Prices for existing users of Luminar Neo:

Ecosystem Pass: $69

Upgrade Pass: $49

Prices for legacy users of previous Luminar versions:

Luminar Neo Cross-device Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile): $89

Luminar Neo Max Perpetual (Desktop + Mobile + Spaces): $109

Why I chose the Pentax Q7 to capture a European river cruise vacation

Is the Pentax Q system the ultimate travel camera? Decide for yourself after checking out the results on our European river cruise.

Convenience, quality wrapped in a tiny package makes Pentax Q series the perfect travel cameras

Okay, before you start laughing, let me explain.

Yeah, the miniature 20-plus-year-old, Q7 mirrorless camera with its tiny 12.3 megabyte 1.17-inch backlit CMOS sensor would not be many photographers first choice to document a once-in-a-lifetime family Rhine river cruise vacation.

In fact, I’d bet I’m probably standing pretty much alone here, with maybe the exception of all but the most die-hard Pentax Q users.

And that’s fine with me.

Pentax Q: Tiny and terrific

The Pentax Q with its fine collection of proprietary lenses, just might be the best travel companion for those simply looking to document their vacation with a high-quality camera and lenses that is small enough to fit into a coat pocket.

The purpose of the vacation was not to capture incredible images, rather it was to spend time with my wife and adult daughter. In other words, I felt the experience was going to be more important than the images I was going to make on the vacation. Afterall, time limitations and tourists getting in the way makes serious photography difficult on these types of vacations, to say the least.

Complete system fit nicely in a coat pocket

I figured the Pentax Q system was, at least, better than relying on my phone for capturing memorable moments, and, being able to fit the miniature camera and all three lenses into a coat pocket would allow me to grab the odd shot without having to lug around a full system of cameras and lenses. I’ve made that mistake too many times in the past and was determined not to make it on this vacation.

So, after much thought prior to the trip, I convinced myself that, because of the limiting factors of time and an abundance of tourists, at best I was going to get a couple of nice snapshots.

Boy, was I wrong and more than a bit surprised..

But more on that later. Let’s continue this talk about the interesting camera decision.

For more on the Pentax Q system, check out my other posts below:

The tiny Pentax Q7 fit nicely in my coat pocket and could be easily retrieved at a moment’s notice to capture an iconic scene like this one of a man walking down a deserted street in the heart of a quaint German town. (Pentax Q7, ISO 1600, 1/125 sec, F5, with 02 standard zoom at 14.9mm.)

Sigma DP2, Fujifilm X10, Olympus and Lumix micro 4/3 cameras all stayed home

My camera choice certainly wasn’t because the Q10 and accompanying lenses were the best I had available to me. I’ve got Olympus and Lumix M4/3 systems, A Pentax APS K5 system, the venerable Fujifilm X10, the Lumix LX7, even a Sigma DP2 as well as a host of other cameras to choose from. (I know I have a problem.)

But when it came down to it, I chose the Q7 along with the 50mm (01) equivalent, 28-80mm (02)kit zoom and the weird little fisheye lens. I meant to take the 80-200mm equivalent (06) to give me some pull-in power, but in my haste to pack everything, I grabbed a second 28-80mm kit lens instead.

I should say that I also packed a Fujifilm EXF660ER travel camera with a 16mp CMOS sensor and 24-360mm zoom lens, which I had purchased a few weeks earlier from a thrift store for $12 Canadian. Its 360mm reach easily took the place of the 80-200mm 06 lens for capturing distant scenes. However, the Fujifilm was used only sparingly and often when the Q10 battery died while out on the town.

Would I do it again? In a heartbeat.

But, rather than explain my decision and trying to justify it to an audience that can’t imagine bring the tiny Pentax instead of a larger format system, let me show you why.

I think these images speak for themselves.

Montreau, Switzerland taken with the Pentax Q7 from the Lake Geneva boat cruise. (Pentax Q7, ISO 100, at 320 sec at 9.1mm.

From past experience, I knew the Pentax Q system was capable of capturing exceptional images. Despite the tiny sensor, the camera boasts the ability to shoot both high-quality JPEGs as well as RAW (DNG) files, has very capable image stabilization built into the camera and no anti-aliasing filter to soften the image. I believe the lack of anti-aliasing filter is often overlooked by many, but accounts for the very sharp images achievable straight out of camera.

The results point to a surprisingly capable camera system more than up to the task of capturing extremely sharp images with the array of dedicated lenses. This is not even taking into consideration the huge number of third-party lenses that can easily be added to the system from the diminutive 110 lenses (see story here) to a host of manual lenses via a simple adapter. (seee story here)

Before the trip, I added a step-up ring which, in turn, allowed me to use a polarizing filter to deepen the blues in sunny skies and remove unwanted reflections from water, windows and other reflective surfaces.

After going through almost 2,000 images, I think I can safely say that I was not disappointed. In fact, once again, this little camera system managed to impress me even more than I expected.

I was careful to photograph everything in both Jpeg and RAW formats and, although the JPEGs were more than useable, I chose, in most instances, to work with the RAW images in Lightroom to pull out fine detail and a wider exposure range. The RAW DNG files proved to be incredibly easy to manipulate and arrive at the results I was wanting to achieve.

To my surprise the kit zoom (02) that gives a zoom ratio of approximately (28-80 range) with the Q10, was used for maybe 80-90 per cent of the images. Most of the images included the polarizing filter, if nothing else to cut glare.

Eight dedicated lenses to choose from

For a little background, Pentax introduced a total of 8 miniaturized lenses beginning with the excellent 01 standard Prime with a focal length of 8.5 mm (47mm equivalent for the Q, Q10, and 39mm for the Q7, Q-S1 with the larger sensors.) More lenses followed: 02 standard zoom (27-80 range equivalency, 23-69mm), 03 Fisheye (17.5mm, 16.5mm), 04 Toy wide angle lens ( 35mm, 33mm), 05 Toy lens (100mm, 94mm), 06 Telephoto zoom (83-249mm, 69-207mm), 07 Shield mount lens (63mm, 53mm) and finally the 08 Wide Zoom (21-32mm, 17.5-27mm). For more complete story on the hard-to-find O8 wide angle lens click here.

The lake cruisers traditional looks and almost silent motors made the Lake Geneva cruise a real joy. (Pentax Q7, ISO 200, 02 lens at f4 and 5.5mm.)

One of the weaknesses of the Q system is their tiny batteries which do not hold the best charges. I carried two batteries most days, but was able to get through the majority of days with a single battery by conserving the power by turning off the camera immediately after using it and keeping chimping (checking the images on the back LCD screen) to a minimum.

Keeping an eye out for interesting “street” images adds more depth to your typical vacation photographs and helps to capture a greater sense of the local character.

Ideal system for capturing street scenes

As a former journalist, capturing interesting street scenes was a prime focus whenever I was wandering the small towns and cities where the river cruise ship stopped. Nothing screams professional more than a large 35mm camera and an array of lenses cascading out of the camera bag. That’s not the image I wanted to convey while wandering the back streets trying to capture street scenes.

A couple strolls down the quintessential European street in the heart of a quaint German town (Heidelberg I believe). (Pentax Q7, ISO 400, F4, with 02 standard zoom at 11.2mm.)

Nothing could be more inconspicuous than the miniaturized Pentax Q system. Even with the 80-200mm f2.8 mounted on the camera, no one is going to mistake you for anything more than an annoying tourist, if they even notice you are photographing them at all. The whole package is so small that, if you are shooting from the hip, I can guarantee no-one will take notice.

This well-dressed woman seemed to be taking a moment to do a little people watching or maybe waiting for a friend, but I could not resist capturing this captivating scene.

These are just a few “street scene” images taken during our two weeks in Europe. I hope to write a separate post on capturing more authentic images on vacation rather than just your family members posing in front of typical tourist destinations, which will include capturing street scenes.

Window boxes with European style

It’s hard not to notice the sheer abundance of window boxes and container plantings throughout the small towns and cities in Europe. In this post we explore the world of European window boxes.

Tasteful, minimalist approach adds an unforgettable elegance

When it comes to window boxes, Europeans know how to do it with a flair for simple elegance.

But that should come as no surprise, they’ve been doing window boxes for longer than North America has even existed. Like most things, simplicity wins out everytime.

A two week vacation through Switzerland, the Netherlands, France and Germany helped me really appreciate the Europeans’ approach to gardening in small, urban spaces.

Now, there’s no doubt our river cruise through the Rhine valley from the Netherlands through to Switzerland focussed on some of the most beautiful small tourist towns along the historic river, centered around some of the most beautiful European towns and cities. However, I’ve seen my share of tacky tourist towns, and these were not them.

Geranium simplicity

Three red geraniums are all it took against this grey background and simple sheer curtain to create a memorable image and hi-light this simple window.

It helps that the ancient buildings all seem to have beautiful exteriors to set off the windows, colourful shutters and window boxes. However, even without window boxes, or flowers, they can still be stunning.

Even windows without window boxes and/or flowers have a certain simple elegance about them.

The boxes themselves are most often planted with a single flower or colour in great abundance creating a very full display spilling out against the perfect backdrop.

But, just as many window boxes seemed to take the minimalist approach where a trio of airy plants were used to just add a colourful highlight to an already elegant backdrop.

Simplicity in colour

The combination of the massive display framing the doors and windows of the commercial storefront, complement the smaller, yet elegant second-floor display of window boxes.

Throughout the many walking tours we took, I found myself regularly wandering away from our guides to focus on the incredible window boxes and containers that seemed to line every street, whether it was a main shopping area, or a lovely, quiet side street that begged me to go exploring on my own.

Everywhere I turned during this early September vacation seemed to bring new flower displays – almost all of them stunning in either their simplicity or their bounty of colour.

Even the traditional light standards that lined most of the streets offered tremendous picture potential for anyone who took the time to look up and fully appreciate the details that made these areas special.

Picturesque Light standards

Light standards lined the streets of most towns, and like the window boxes, were planted in a simple yet elegant style.

Rather than try to explain the European approach to window boxes, I think the following photographs will give you a taste of what you can expect if you choose to take a European river cruise. Images also tell the story better than I ever could.

The following are just a few of the window boxes and containers that caught my eye during my time in Europe.

I want to add that flowers play an important role in European life. Nothing illustrates that better than a simple flower shop (below) I stumbled upon on a side street. The attention to detail is outstanding and both the interior and exterior displays are outstanding.

You know that the French take their flowers very seriously when they have guard cats watching over their displays. This scene was caught on one of the side streets in Stasbourgh, France. After I stumbled upon a lovely flower shop and could not resist exploring the photographic possibilities. I never expected to come across this scene, but took the opportunity to capture it as soon as I saw it.

The flower shop that housed the cat was unlike any I have seen elsewhere. Sitting on a quiet corner, the owners took advantage of the outdoor space to create a lovely display of both flowers and fruit for passersby. In the European culture, it is not uncommon to pick up groceries – particularly a baguette – on the way home from work. Adding a lovely bouquet of flowers is also a practise that other cultures might want to pick up on to make their world a little more beautiful. Below, is the flower shop that I could not resist exploring.

How could anyone walk past this glorious display without stopping to at least look at flowers and fruit let alone purchase a small bouquet for the table? Flowers are a much bigger part of the European culture than they tend to be in North America. Sometimes, it’s the smallest things that makes one smile and lights up a room.

Six window boxes done with simplicity reflecting the elegance of the terra cotta coloured window frames. As a photographer, the colourful window boxes certainly caught my eye, but so too did the lovely reflections in the window. Of particular note is the glass in many of the window panes. Many were original panes of glass that created the uneven reflections.

Simply Elegant

Even in areas where there was not a lot of open area for full gardens, flowers were everywhere.

The above is a sampling of the images captured during the two-week period. I hope they give readers new ideas on using simple window boxes in their own gardens, even if those gardens are nothing but a small balcony or courtyard. Be sure to go to my photo gallery featuring many more window box images as well as colourful containers that are just as popular as the window boxes.

You will find the Photo gallery of window boxes and containers here.

The photographic approach

Without getting into the fine details about my photographic approach to capture these images, let me first say that I chose not to use my smart phone, which is more than capable of capturing similar images. For almost all of these images, I used a 20-plus-year-old miniature mirrorless camera made by Pentax. The Pentax Q10 is a tiny mirrorless camera that has its own interchangeable lenses.

All the images were post processed with a combination of Lightroom/Photoshop and/or Luminar Neo.

I will be posting separately about several photographic approaches I took as well as the camera(s) used.

Getting a grip on the Sigma DP series cameras

The incredible Sigma DP series of cameras with their minimalist approach to design combined with an outstanding foveon sensor makes them a true cult camera. Adding a third-party 3-D printed grip only makes the cameras even better.

Third-party grip takes street photography to a new level

Let’s start by saying I love the minimalism of the Sigma DP1 and DP2. Their simplicity, along with their incredible foveon sensors give them special status among the many high-end point-and-shoot cameras in my arsenal.

My Sigma DP2’s brick-like look and feel is perfect when I’m using it out of a camera bag or from a tripod capturing landscapes in the woodland. However, when it comes to street photography, I like a good grip to give me the assurance I’m not going to accidentally drop one of my favourite cameras.

That’s when Shutterspeedblog’s creative expertise comes into play with its outstanding grips for the Sigma cameras as well as a host of other high-end cameras from Leica, Canon and Lumix just to name a few.

Sigma Hand grip

The 3-D printed grip has been meticulously designed to incorporate both a grip and thumb rest, while allowing access to the battery and SD card.

There is something comforting about walking around town with the Sigma DP2 hanging off your fingertips ready to capture anything that catches your fancy. Of course, I use a simple wrist strap for a little added insurance, but the camera sits nicely in my hand with just the grip. The built-in thumb rest is added security and helps me to hold the non-ibis camera still during longer exposures.

Grip and build-in thumb rest

This overhead view shows the grip and build-in thumb rest that helps to make street photography style shooting with eh Sigmas that much easier.

The meticulously 3D printed grip also allows access to the battery (and we all know how important that is for the battery-eating Sigmas) and SD card, to make the entire experience seamless.

Want to remove the grip? Unscrew it from the tripod mount. Want to still use the camera on a tripod? No problem, there is a separate, yet very sturdy tripod mount built into the grip.

There is no doubt that the very reasonably priced grip significantly improves the handling of the camera. Depending on the size of your hands, some of the buttons on the back of the camera might be a little more difficult to reach, but that is a miniscule price to pay for the convenience the grip provides.

Lumix LX7 grip

Similar grips are made for Lumix, Leica, Canon and other high end point and shoot cameras.

I decided to give it a good workout during a walk with our new dog down the Main Street of our small town. Walking a dog and carrying a camera loosely in your hand is not always recommended, but the new grip on the Sigma made it not only possible, but immensely enjoyable. All I had to do is raise the camera and shoot away like a real veteran street-shooter.

I can only imagine how much easier it will be to use the grip on the cameras for someone who regularly shoots from the hip, whether they are using the camera in manual focus mode or autofocus.

The following are just a few more images from my morning walk with our Flat-coated retriever, Colby and the Sigma DP2 and grip from Shutterspeedblog’s eBay store.

Colby goes to church

A quick grab shot of Colby in front of a gothic church door. The grip just makes stealing images like this much easier with the Sigma series of cameras.

Kolari neutral density filters put to the test

Kolari Vision neutral density filter system can turn your simple photographs into works of art.

Digital photography is invitation to minimalist fine art images

I’ll admit that I have not used neutral density filters all that often. I mean, growing up shooting Kodachrome 25 and 64 as well as Fujichrome 50 meant there was not a whole lot of need to put darkened glass in front of my lenses to get an even slower shutter speed.

But that was long ago and times have changed.

Image taken without a neutral density filter at 1/200th of a second.

Today’s modern cameras boast ISO settings that easily reach into the thousands and some cameras don’t even offer ratings under ISO 200. So, using neutral density filters has become increasingly important in order to create certain in-camera creative effects.

A waterfalls, for example, takes on a beautiful soft look with a slower shutter speed. Even a simple stream looks better when a slow shutter speed has been used to create a soft ethereal look.

An long exposure of anywhere between 10 seconds to several minutes or more creates a dreamy, ethereal look as ocean waves crash against the rocks. The results can easily transform a typical tourist shot into a work of art anyone would be proud to hang on their wall.

The image below – although admittedly not very exciting – illustrates how a long exposure (16-seconds) can remove wave action and create a minimalist image with an ethereal look. (I’m going to work on finding better subjects for a future post on maximizing the 10-stop filter.)

A 10-stop neutral density filter was used to create this 16-second exposure of a rock in the lake. The long exposure flattened out the water, removing the waves and helped create this soft, ethereal feeling.

These are the more obvious, and popular, uses of neutral density filters. There are, however, so many more uses that photographers might want to explore.

One of the benefits of digital photography is that there are no longer excuses to not experiment with your camera. In the past, experimenting with a roll or two of film cost real money, especially if you were not happy with the results. Today’s digital cameras, however, take the cost factor out of experimentation and leaves photographers with the incentive to pursue a more creative, experimental approach to making photographic images whether in the garden, in the forest or even by the lake or ocean.

Filters in original case

The three Kolari ND filters are nicely packaged in a quality case with the magnetic adapter ring.

Kolari kindly offered me a set of their magnetic-based neutral density filters (a 3-stop, 6-stop and 10-stop filter) to use in the garden, in the woodland and in the field. In the short time I have been able to put these filters to the test, I have to admit that I am impressed. Not only with their ease of use, but with their neutral colour profile and exceptional clarity.

That should not come as a surprise since Kolari is using Schott glass – considered the finest in photographic glass – for their filters.

Let’s take a look at some of my early results employing these filters.

The three images above illustrate the effects of a slow shutter on moving water. The top image shows a 12 second exposure while the small image below shows a typical 1/200th of a second exposure. A tripod was a necessity for the 12-second exposure.

Better Bokeh, create a softer background

One of the important uses of neutral density filters is how they allow the photographer to create a softer, more pleasing bokeh or background in their images. This is especially important if you are photographing in brightly lit areas where your camera is calling for small f-stops like f8, f11 or f16.

By adding one or more neutral density filters to the lens, you are able to choose f-stops like f5.6, f4 and f2.8. This is especially important for portraiture to help the photographer “soften” the background.