Garden Revolution: Ecological gardening made easy

Garden design book is guide to low-maintenance landscape

It’s not everyday you come across a book that changes the way you think and the way you do things.

Garden Revolution just may be that book.

The full title of the book, published by the highly respected garden book publishers Timber Press, helps provide a better idea of where the authors were going when they wrote the book: Garden Revolution: How our landscapes can be a source of environmental change.

I like to think that the authors and I have been on the same wavelength for the past decade or two, with the only difference being that they took it to a level far beyond anything I could imagine.

The book is just another illustration of why using native plants, trees and shrubs in our landscapes is not only good for the environment, but for our own gardening success.

For my article on why using native plants in the garden is important, go here.)

The basic premise of their philosophy being: Let nature do most of the work.

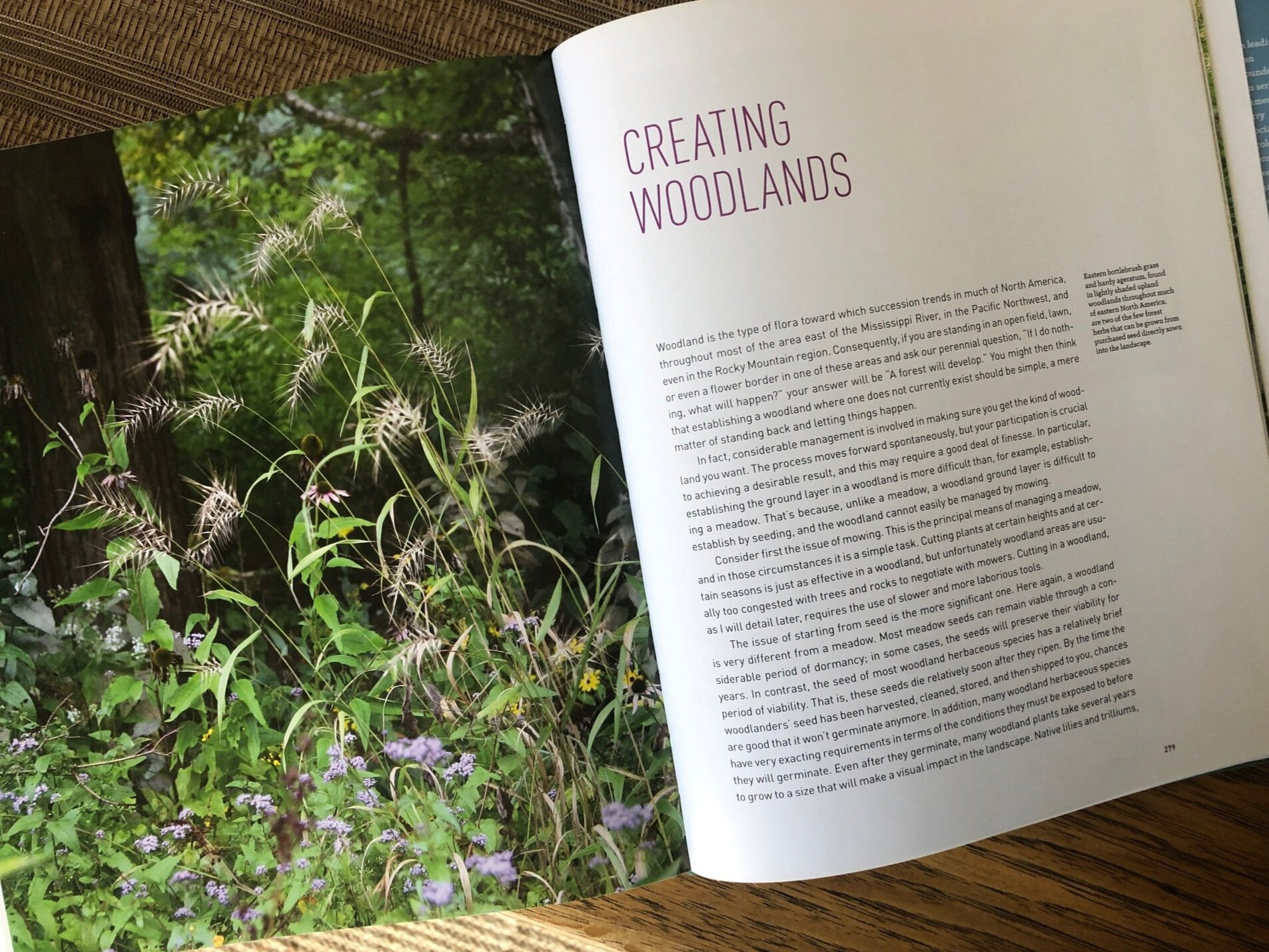

One of the last chapters in the book focuses on the steps needed to create and maintain an ecologically-based woodland garden.

The result: A low-maintenance ecological garden design that takes most of the work out of the installation and management of even large landscapes.

It’s an approach I have been interested in for years and have certainly been practising in my own woodland/wildlife garden, much to my neighbours’ chagrin. In my case, laziness plays a major role. The authors, on the other hand, use Mother Nature on a grander scale to control huge expanses of meadow, shrubs and woodland gardens using mostly native plants that would be impossible to maintain with traditional garden approaches and methods.

And the results are often stunning.

Don’t take my word for it. Doug Tallamy, native plant guru and author of Bringing Nature Home and The Living Landscape, puts it simply: “This beautiful book shows us that guiding natural processes rather than fighting them is the key to creating healthier landscapes and happier gardeners.”

“This beautiful book shows us that guiding natural processes rather than fighting them is the key to creating healthier landscapes and happier gardeners.”

Tallamy goes on to describe the book as “an essential addition to our knowledge of sustainable landscapes.”

The authors, Larry Weaner and Thomas Christopher surely know of what they write about in this beautifully illustrated coffee-table book boasting more than 320-pages of garden knowledge, shortcuts and solutions to so many of our garden issues.

Weaner, a leader in North American landscape design and founder of the educational program series New Directions in the American Landscape, is owner of a highly successful landscaping firm well known for combining ecological restoration with traditions of fine garden design. It’s so successful, in fact, that it has received the top three design awards from the Association of Professional Landscape Designers.

His co-author, Thomas Christopher, is the author of several gardening books and a graduate of the New York Botanical Garden School of Professional Horticulture. He has been creating gardens for clients for forty years.

Together they present a convincing case for adopting ecological principles to create living landscapes that are both alive with colour, while at the same time being extremely friendly to local wildlife.

As the authors point out in the book’s introduction: “For all of those (gardeners) galvanized by the message of such environmental gardening manifestos as Sara Stein’s Noah’s Garden and Doug Tallamy’s Bringing Nature Home, this book is the next step, the way to turn philosophy into practice.

In their “alternative approach” to garden design and maintenance, the authors set out to prove that: “less is truly more. Minimizing intervention and letting the indigenous vegetation dictate plant selection and, as much as possible, do the planting, producing a garden landscape that flourishes without the traditional injections of irrigation and fertilizers and is better able to cope on its own with weeds and pests.”

They tackle the task by first guiding us through the learning process. They introduce readers to the importance of ecological gardening, and work to convince them to play a part in reversing the harmful habits into which much of gardening has fallen.

“There are powerful environmental reasons for bringing our gardens into a sounder relationship with nature,” writes Weaner, who goes on to explain that he realizes that doing the right thing is not necessarily going to convert the majority of gardeners. Instead, he focuses on a more selfish motif – getting out of doing work.

“I honestly believe that having once sampled an ecologically driven approach, gardeners won’t want to do anything else. For me the most persuasive reasons are that it’s easier and far more rewarding to transform the human landscape in this fashion.”

If you are looking for a gardening book, be sure to check out Alibris for a great selection of ne and used books.

• If you are considering creating a meadow in your front or backyard, be sure to check out The Making of a Meadow post for a landscape designer’s take on making a meadow in her own front yard.

Five lessons to learn from this book

• It’s important to work with nature rather than against it. As the authors points out, gardeners who follow the advice of the book will learn to “form a partnership with nature.”

• Refrain from tilling the soil or doing any other action that will disturb the top layer of soil and free weed seeds lying in wait to sprout. This includes pulling out weeds. Better to cut weeds off at soil level to starve them of sunlight than to pull them out and expose previously buried seeds and open the soil up for future weed growth.

• Whenever possible, encourage existing native plants to reseed themselves around the garden especially in large swaths of open meadows.

• Most land in North America wants to return to forest if left alone. In other words, if we do nothing to manage our property, it will, over time, return to a woodland.

• In typical woodland garden, there are three distinct zones – the interior, the edge, and the canopy gaps. Within these zones, there are 4 vertical layers to consider: The upper canopy layer, understory tree layer, shrub layer, and ground layer. If any of these layers are missing, they must be returned to the woodland.

Their ecological approach does away with most tilling, weeding, watering and fertilizing plants. Tilling, for example, only opens up the soil for existing weed seeds to germinate. Spending hours weeding is again a counter-productive endeavour because it once again exposes the soil to ever more weed seeds. Instead, their approach is to leave the soil undisturbed as much as possible and encourage plants to reseed naturally without much if any intervention on the gardener’s part.

Rather than digging out weeds, it’s better to simply cut them off at soil level to restrict photosynthesis. Eventually, more dominant plants can be used to crowd the weeds out.

This ecological approach, while feasible on a small scale, really comes into its own on large-scale gardens that cover acres of open fields, scrub lands and forests.

In the chapters on design, the authors tackle site analysis, creating a master plan for the garden, and developing a synergistic plant list.

Then the fun really begins. In the Field chapters, readers begin to understand how the ecological process plays out. It’s fascinating to read the real-life experiments and results the author has watched unfold in his many projects and how the traditional landscaping industry began to recognize the value in this revolutionary approach.

Three garden types to explore

Three key chapters explore the most dominant naturalistic-styles: The creation of meadows and prairies, the creation of shrublands, and finally the secrets to creating successful woodlands.

The process behind the creation of a woodland is of particular interest here, so we’ll explore that in a little more detail.

Not unlike Mary Reynold’s book The Garden Awakening, (see earlier post) The authors of Garden revolution start with the premise that if left to its own devices, most open land, whether it’s a meadow, scrub land or perfectly manicured lawn, will return to a woodland.

In other words, the authors write: “If I do nothing, what will happen?” your answer will be “A forest will develop.”

The problem is, a considerable amount of management is needed to ensure that a proper woodland emerges. The first problem is establishing the ground layer in the woodland. Unlike a meadow, which can be managed primarily by mowing at different heights and at different times of the year, Woodlands are too congested with trees and rocks to use mowers.

The herbaceous species on a woodland floor often have very specific needs in terms of proper soil and seed germination. Add to that the fact that even after they germinate, many woodland plants take several years to grow to a size that will make a visual impact in the woodland.

Complicating the process further is that most woodlands have three distinct zones – the interior, the edge, and the canopy gaps. The type of trees in the woodland will play a major role in the levels of shade in the interior of the woodlands. That, in turn, will play a role in the types of plants (both invasives and non-invasive) that will take up residence there. The decision to increase tree density or thin-out the woodland will depend on whether the existing vegetation is largely native or primarily an invasive, exotic species.

These are just a few of the difficulties faced in the creation of the woodland garden.

Layers in the woodland garden

Important too are the vertical zones of the woodland.

“You should also examine the vertical layers within the woodland to determine which, if any, are missing or sparse and, if so, why.” Deer, invasive species, and human activities may all be responsible for the destruction of any one or more of the layers.

The authors provide detailed explanations of the four layers of the woodland garden and explain that any that are missing need to be replaced by the gardener.

The four layers are described as:

• canopy tree layer, which is the topmost layer, the interlacing of branches and foliage that shades all below them.

• understory tree layer, which consists of both permanent understory trees like serviceberry, pawpaw, and dogwoods, as well as saplings of future canopy tree that occupy the space only temporarily.

• shrub layer, which consists fo the shrubs that flourish under and among woodland trees; and

• ground layer, the lowermost layer consisting of herbaceous or prostrate woody plants on the woodland floor.

The chapter goes on to explore in detail everything from managing the woodland, to woodland soil, planting for natural succession, the use of pioneer trees to foster mature forest species, and natural recruitment.

In the end, the authors, in describing the “Big Picture” explain that: “when working with estblished woodland, your initial goal should be to transfer the vegetation from exotic, invasive species to a flora dominated by native ones. Once this has been accomplished, you may take as your subsequent goal to translate the vegetation from generalist native species to more specialist natives.”

Okay, this all sounds like a lot of work to me. What happened to letting Mother Nature do all the work?

I guess it all depends on how far you want to take your woodland, meadow or shrub garden.

As the authors explain: The phrase “a partnership with nature” has been around for a long time, and I never paid it much attention. From a practical standpoint, I really didn’t know what it meant. Now I think I do.”

This partnership with nature is something every gardener needs to embrace. Working with nature rather than against it, is not only good for the environment but it will make our lives much simpler, our gardens easier to manage and the wildlife we share with it much happier.

Do yourself a favour and get this book. Read it. Study it, and read it again.

Adopt the philosophy. Have a glass of wine or another cup of coffee and relax.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

Native moss in our gardens

This page contains affiliate links. I try to only endorse products I have either used, have complete confidence in, or have experience with the manufacturer. Thank you for your support.