The Garden Awakening will change the way you garden

Mary Reynolds’ The Garden Awakening is an important book during these troubled times. It is both a gardening book and a road map we all need to follow into the future. For some it is a treasure map to help them rediscover nature and themselves. For others, it will provide them with a new way of looking at their gardens, their land and their life. Please, click on the link for the full review.

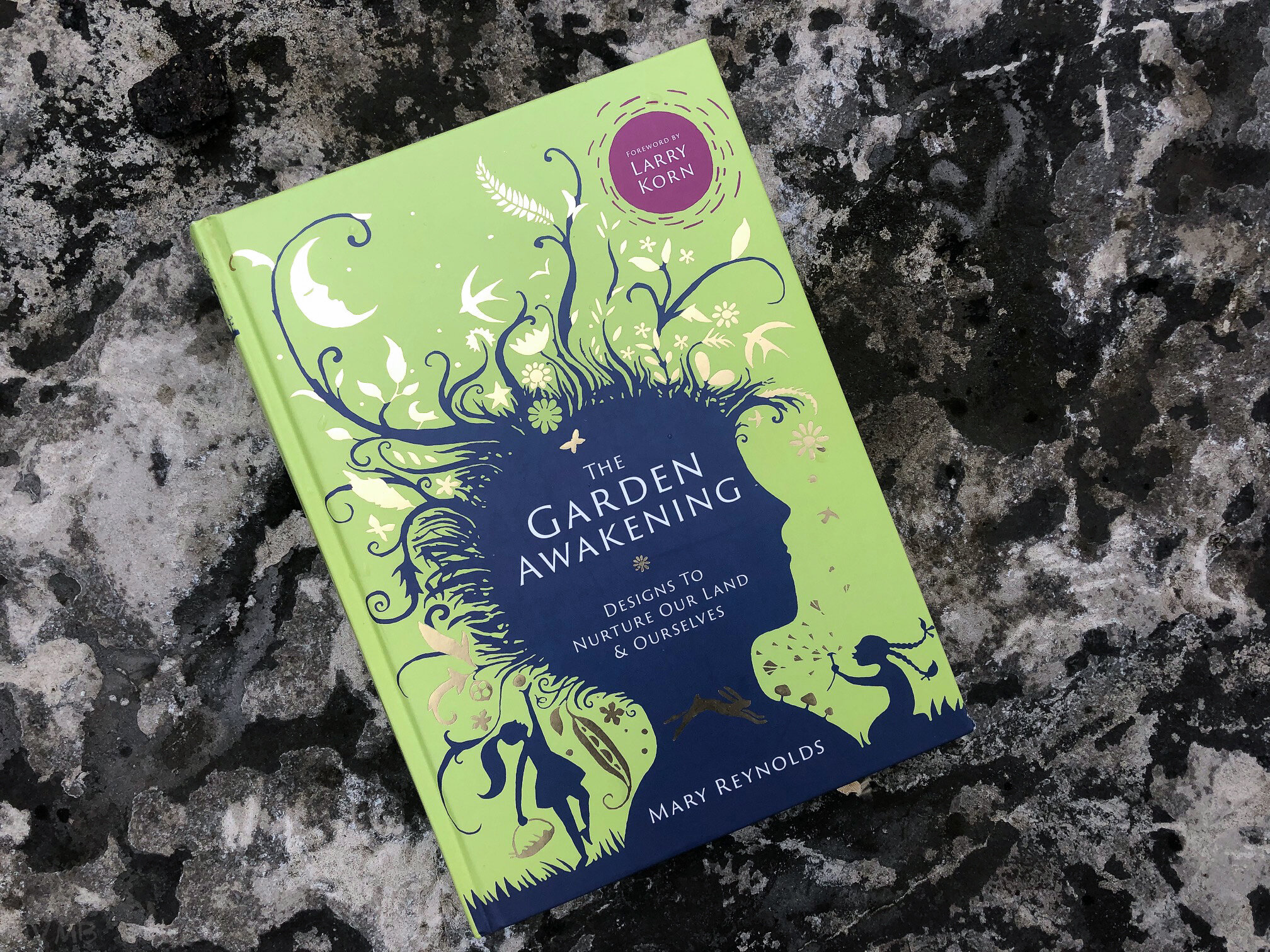

The Garden Awakening

Designs to Nurture our Land & Ourselves

By Mary Reynolds

“If nature is left to its own devices and without imbalances in the ecosystem such as the overpopulation of hungry deer or an infestation of rabbits it will reclaim its territory and become Woodlands once more.”

This might be one of the most inspirational gardening books I have ever read.

It’s certainly not your average how-to gardening book. If you are looking for a typical gardening book, The Garden Awakening might not be for you.

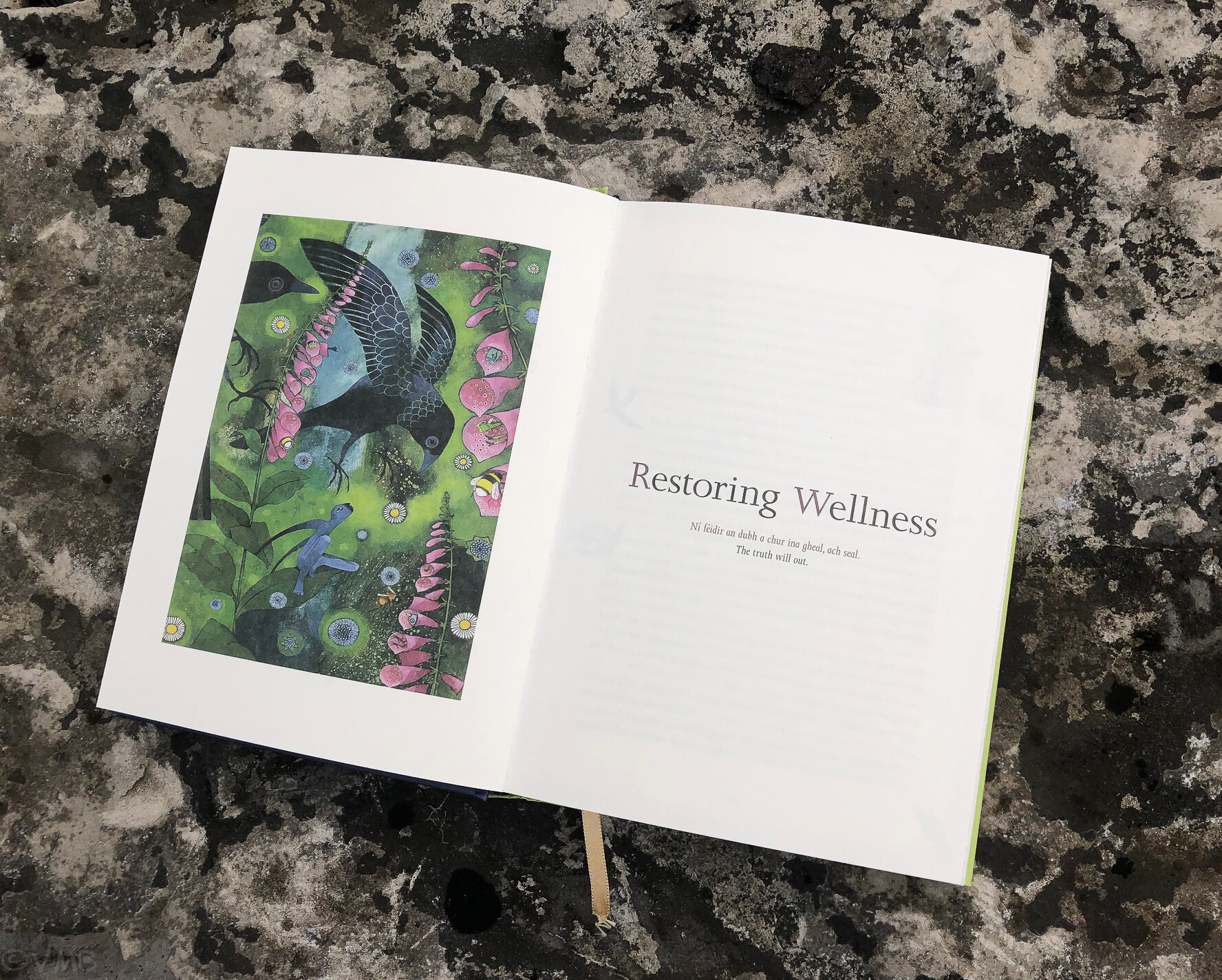

Beautiful illustrations by artist Ruth Evans both on the cover and throughout the book.

But if you are interested in the environment, restoring your garden to a healthy, productive space and/or creating a Woodland naturalized garden, then you owe it to yourself to spend some time with Mary Reynold’s book, The Garden Awakening, Designs to Nurture our Land & Ourselves and her vision for the future of gardening.

Since this writing, Ms Reynolds has published a second informative book titled We Are The Ark. This follow to The Garden Awakening, expounds on her successful approach that each garden can be a small Ark in a world for where wildlife desperately needs our help.

For more information on using native plants to restore your garden, take a moment to check out my article on the importance of using native plants in your garden. For full post go here.

An important book at a crucial time

The Garden Awakening is an extremely important book for the time. It’s a reminder that we are destroying the very land we depend on for survival. It’s a reminder that the world we live in cannot continue to absorb this abuse and not unleash its own fury back upon us.

And, as climate change continues to change the world we live in, it’s important that we as inviduals take action to stem the tide.

But Reynolds offers solutions to problems that we need so desperately in these trying times.

Her inspirational book actually provides a roadmap for anyone interested in doing their part to not only protect but revive the land they live on. Along the way, she provides a “treasure map for finding your way back to the truth of who you are.”

“We are the ark” movement

Be part of the movement

Her movement, “We are the Ark” is bringing together like-minded people around the world to join her in creating a healthy environment, one garden at a time. It provides an important stepping stone to a better environment, a healthier garden and a more optimistic future.

“Gardens were like still-life paintings; controlled and manipulated spaces.... somehow, somewhere along the way gardens had become dead zones.”

If Ireland’s feisty Mary Reynolds is not familiar to you, I suggest you watch a movie called Dare to Be Wild, which maps her journey from an outsider to a gold-medal winner at the prestigious Chelsea Flower show. The movie used to be available on Netflix, but I notice that it is no longer available. (The link provided above will take you to Amazon where it is available as a DVD.)

The movie led me to her book, her vision and her unique and thoughtful approach to gardening.

To purchase the Mary Reynold’s book, here is a link from the excellent book seller Alibris: Books, Music, & Movies for The Garden Awakening. Below is the Amazon link.

For those without access to the movie, take note; Mary Reynolds was the youngest garden designer to win the highly coveted gold at the 2002 Chelsey Garden Show. That alone should be enough to interest you in her book.

Reynolds doesn’t waste much time getting to the point. She describes a vision of her embodying a crow flying over the landscape where she comes across a woman (let’s call her Mother Nature) in a forest clearing. She is then swept up high into the heavens and when she finally wakes up she comes to the instant recognition that she “shouldn’t make any more pretty gardens.”

She realizes that she must be guided by the natural world, rather than pure beauty, in her work as a garden designer.

Unlike nature, “gardens were like still-life paintings; controlled and manipulated spaces.... somehow, somewhere along the way gardens had become dead zones,” she writes.

Being in harmony with nature

The revelation that she was “failing to work in harmony with nature,” eventually leads her to unveil 5 garden design ideas in a system aimed at helping anyone, including gardeners, connect with nature.

Throughout the book, Reynolds returns to her Irish roots and uses folklore to help explain her spiritual views of nature and gardening.

Of particular interest to Woodland gardeners, Reynolds explains that all land strives to become a mature Woodland and the job of the gardener is to allow the land to become what it desires to be.

She also encourages people to design their own gardens and provides a road map in five chapters. Each chapter slowly opens up the world of garden design and includes suggestions for intimate garden areas; a nighttime place, a praying place, a gathering place…

In another chapter, she talks about designing with the patterns and shapes of nature. This all leads to a chapter encouraging readers to put their garden design concepts onto paper, including several illustrations and designs that help readers visualize their garden design ideas.

Throughout the book, Reynolds offers suggestions on plants, although these plants might not all be appropriate for all garden zones.

The book wraps up with a chapter on Forest Gardening, a style of gardening that seems to be once again gaining in popularity and importance.

Many would say that Forest gardening is a logical extension to Woodland gardening. It involves producing food by developing a multi-tiered Woodland where berries, nuts and root vegetables are encouraged to be grown.

Her forest garden includes seven layers beginning with the upper canopy including a shrub layer, a layer for herbaceous plants a ground cover layer, an underground layer and finally climbers or vines.

This is a book every Woodland gardener will enjoy and learn from. It’s a book that should be required reading for all gardeners at a time when our futures may well depend on it.

If you are interested in having Mary Reynolds help design your garden virtually, be sure to check out my post on Ms Reynolds’ virtual makeovers.

What are the benefits to growing native violets?

Our common native violets are important wildflowers that need to have a place in our gardens and even in our grass.

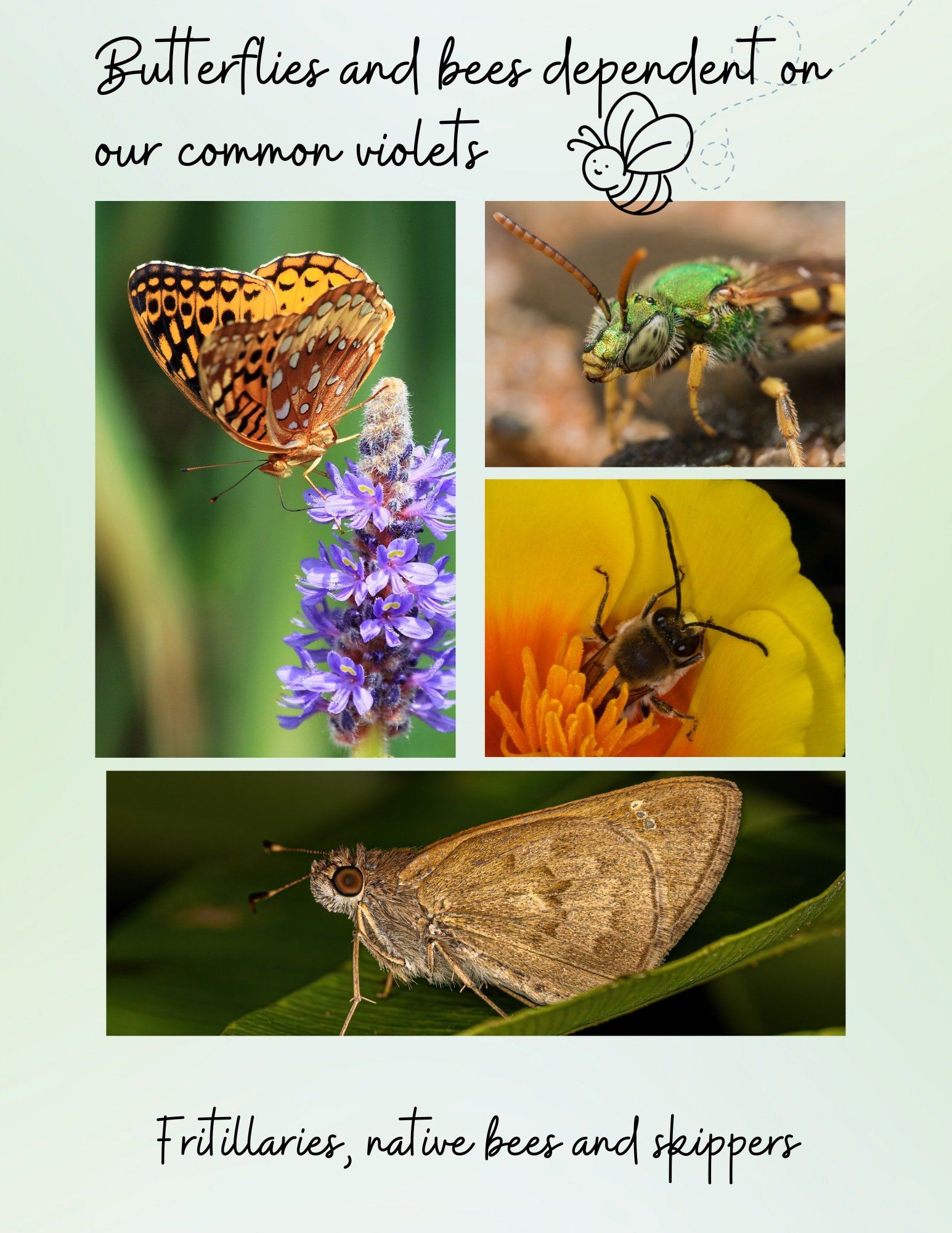

Native butterflies depend on our common violets

In our garden, common native violets are welcome wildflowers.

Whether they are growing happily in the grass or adorning wild areas of the garden, common violets will always have a home here.

I extol the virtues of commonplace violets due to their critical and pertinent role within our local ecosystems. Their vivid purple, yellow and white blooms are a delightful signal that spring has arrived, leading the way for other native wildflowers, which will continue to flourish right through to the summer.

But it is not just their charming appearance that makes them essential; it is their ecological significance that truly stands out.

These little plants serve as host for many butterfly species, particularly the fritillaries, as well as a range of essential insects. This interaction guarantees the perpetuity of these species. Recognizing the significance of this relationship is vital and therefore we should resist the impulse to remove these wildflowers from our yards.

Their presence is not just an aesthetic addition to our landscapes; it is a fundamental factor in ensuring the survival of our native wildlife.

Moreover, I must highlight that violets are not just a symbol of spring. They bloom from the early days of spring continuing into the colder months, bringing colour and life to our gardens even in early winter. This makes them not only a visual treat but also a constant source of sustenance for a variety of local insects and pollinators.

Rather than eliminate them, we need to applaud and appreciate the remarkable roles of such ordinary plants like the violet, in contributing to the biodiversity of our ecosystems.

Our common native violets are host plants to many charming fritillary butterflies such as the Great Spangled, the Aphrodite, Atlantis, Silver Bordered, and Meadow fritillary butterflies.

What does it mean to be a host plant mean, and why does it matter?

Host plants play an integral role in the sustenance of our indigenous wildlife. They are crucial in providing nourishment for the larvae of butterflies and other insects.

The colourful and captivating butterflies we so cherish are in fact bi-products of these caterpillars who, in their initial stages, rely heavily on these host plants for their sustenance and habitat.

However, the fascinating metamorphosis from a caterpillar to a butterfly is a process that requires a bit more elaboration. During this transformation, the host plants serve as the primary source of food and nutrients for the caterpillar. They also provide the much needed sanctuary for these creatures to grow and develop safely.

A prime example of a host plant would be common violets, these nurturing plants are known to host a variety of butterfly species.

In order to conserve these vital host plants, one simple practice we can adopt is to discourage the unnecessary weeding of our gardens and lawns. By preserving these plants, we provide more than just a home for caterpillars, we are supporting the lifecycle of butterflies, and in turn, the vibrancy and balance of our native fauna and flora.

The critical role host plants play is undeniable. Not only do they foster growth and development for caterpillars, they are instrumental support systems to our indigenous fauna and flora.

Where are common violets found?

The common blue violet (Viola sororia), also known as common meadow violet, purple violet, woolly blue violet, or wood violet grow in a wide range across eastern North America in the United States and Canada in areas ranging from zones 2 through 11.

A similar violet (Viola odorata) is a species in the viola family, native to Europe and Asia. Commonly known as wood violet, sweet violet, English violet, common violet, florist’s violet, or garden violet, this small herbaceous perennial has been introduced into North America and Australia.

Although our common blue violet are best known for their spring blooms, common violets can grow from spring into winter, making them extremely important wildlife plants.

There exists a wide variety of 35 Viola species throughout Canada, from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, extending up to the northern treeline. These include varied habitats such as forests, prairies and marshlands. A notable species is the green violet (H. concolor) frequently seen in southern Ontario.

As we said earlier, these Viola species play a crucial role as host plants to a myriad of fritillary butterfly species. Preserving these plants will significantly aid in the survival of our native wildlife, particularly our cherished butterfly species.

Within the realms of the United States, the humble common violet has embedded itself in the core of its native ecosystems. The plant serves as a host to an array of Fritillary butterflies. The importance of its preservation is paramount. The robust flower thrives in zones 2 to 11, surviving from spring to winter, acting as a reliable food source for larvae. As such, it is imperative to reorient our gardening approach from removing these perceived ‘weeds’ to fostering these foundational aspects of our biodiversity.

Native plants in the Pacific Northwest

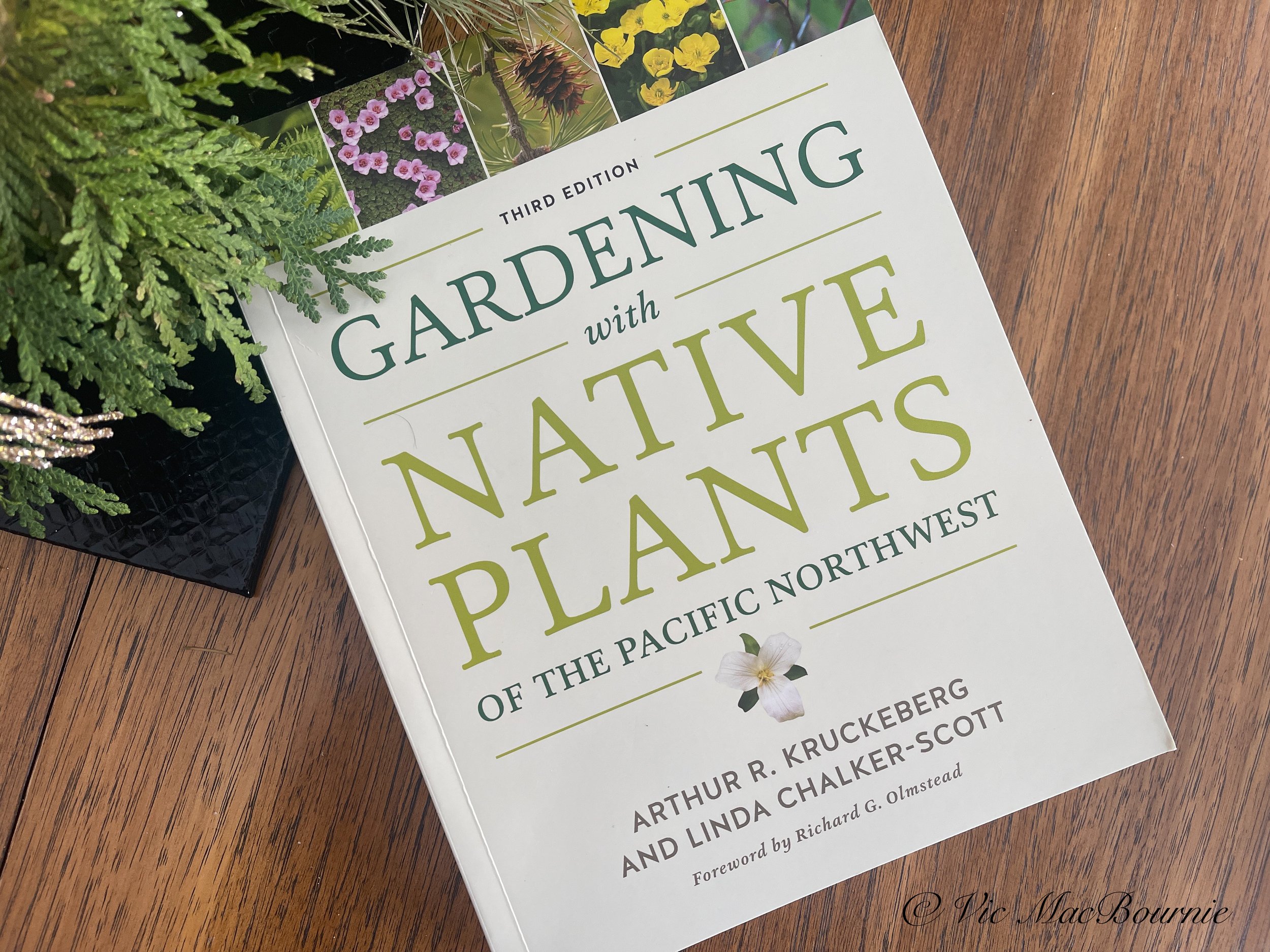

Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest should be a garden bible for anyone lucky enough to call this area home.

How to best use native plants in your garden

The native plants of Vancouver Island and the surrounding areas in the Pacific Northwest forever changed the way I see gardening today.

Two visits to the island and the mainland way back in the 1980s opened my eyes to the beauty of a truly natural landscape, and it was that lush landscape that has burned itself in my memory of what a garden should strive to attain.

Unfortunately, we gardeners in the northeast can only dream of the lush gardens possible in the Pacific Northwest. This thing called winter gets in the way of our dreams of lush, year-round gardens full of unusual native plants that attract four –count them four – species of hummingbirds: Anna’s, Black-chinned, Calliope, and Rufous. Of the four species, Anna’s Hummingbird is the only one found year round in the Puget Sound region of western Washington.

Four species of hummingbird is reason enough to want to call the Pacific Northwest home. But there’s so much more, not the least the abundance of native plants gardeners have access to in the creation of their gardens.

This is where the Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest (Third Edition) comes into play.

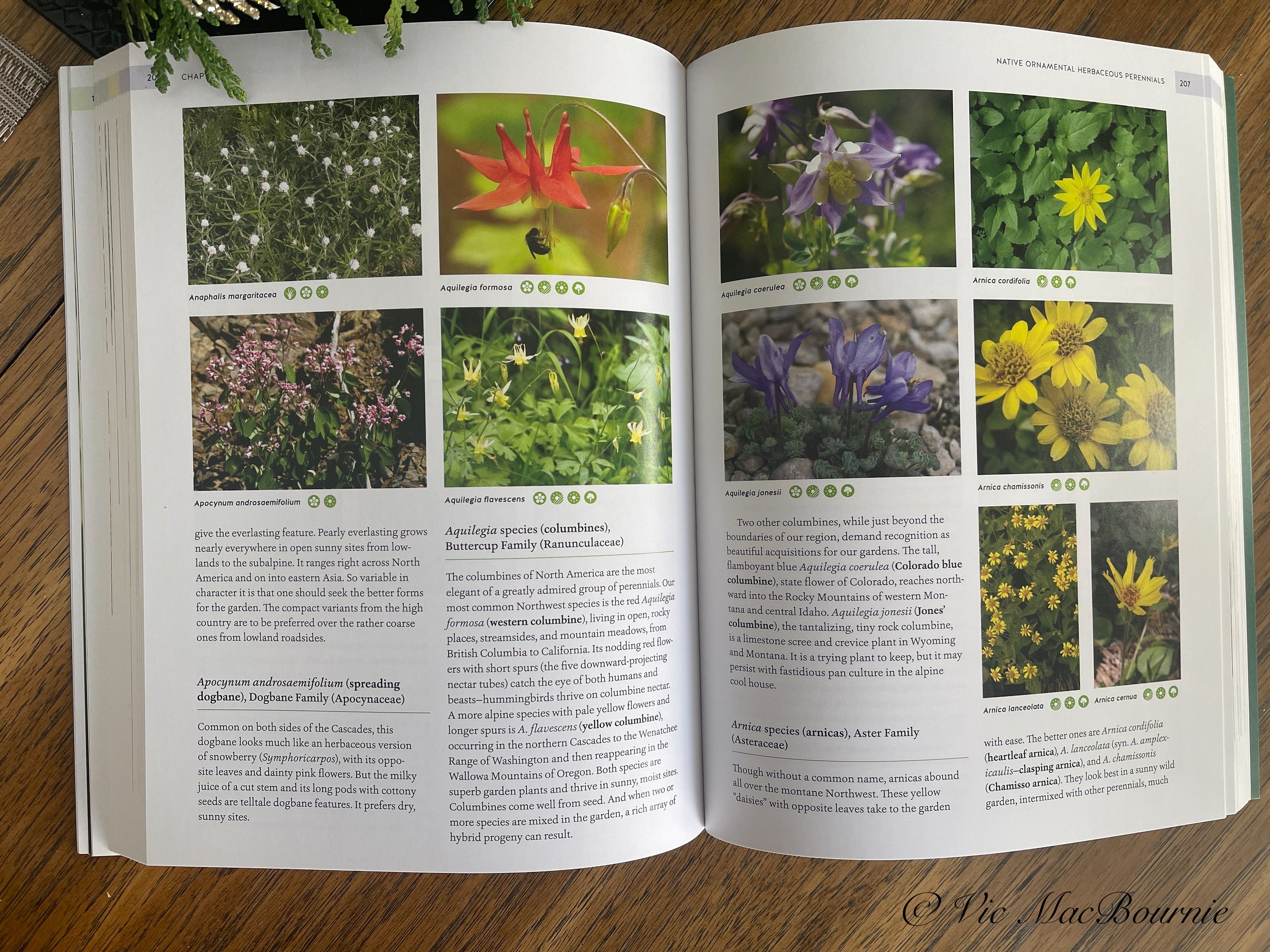

Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest’s more than 370 pages of pure native plant gold is a treasure trove of information, inspiration and motivation for any gardener lucky enough to call this area home. Packed with 948 full-colour images showing the native plants – many in their habitats – as well as in the garden, authors Arthur R. Kruckeberg and Linda Chalker-Scott deliver in almost every way.

Even the introduction answers many of the questions most gardeners new to native plants want answered.

“The key to garden success (using natives) is the compatibility of a plant to its place in the garden,” they write. “This means that natives can easily coexist with exotics in the garden as long as the requirements of the plant – and the desires of the creator of the plantings – are met.”

A garden entirely made up of native plants may be most appropriate in a woodland or semi-wild setting in suburbia, in rural areas, or at the vacation cabin by the sea or in the mountains. And there is often good reason to emphasize natives in such places,” they write, before going on to show examples of dunes in Oregon, a subalpine meadow on Mount Rainier, a seashore at Cape Flattery, in Washington state.

“Planting salal, oceanspray, madrone, and huckleberry in a westside scene that contains Douglas fir can restore the beauty of a natural woodland setting. Once established, the native garden becomes a nearly self-sustaining, low maintenance setting.”

The book is published by the outstanding, garden-focused Canadian publishers Greystone Books. Visit their website at Greystonebooks.com for a complete selection of their books, including some of the most highly sought after gardening books.

Other Ferns & Feathers’ posts based from Greystone books include: The Hidden Life of Trees, The Heartbeat of Trees, The Hidden Kingdom of Fungi, Seed to Dust.

The book can often be purchased on the used market at Alibris Books on-line sellers. In this link there is a copy of the book for less than $4.00.

Still in the introduction to their book Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest, the authors use Herbert Durand’s suggestions in his book Taming the Wildlings, to help readers understand where they can use natives. The result is, of course, almost anywhere but here’s the suggested list:

The small home garden: Perfect for defining boundaries, in borders and groups of shrubs. These natives need to be chosen with special care; matters of scale, quality of colour and texture, and habitat preference are particularly important in the small garden.

Suburban and rural places: Natives can restore “the original charm of neglected woodlands and develop the latent beauty of any forested area.”

The seashore, woodland, or mountain retreat: Natives are ideal for use in lands surrounding vacation homes in areas that were once wild. “The very purpose of a house in the wilds cries out for wildings.”

Parks, open spaces, and Estates: The authors call on more native plants in public gardens and large private estates as well as small parks.

Wildlife sanctuaries: Native plants have long been known to have a close relationship with wildlife and are vital for their future existence. “Plants from the surrounding wils for use in the re-created wildlife sanctuary should emphasize the attributes of shelter, nesting sites, and food. Most native trees and shrubs qualify without question; even though some might not have edible fruit or seed, they surely harbor insects and the like.”

Highway platings: the authors point out the success that has already been achieved with native plantings along highways and call out for more experimentation with different plants, trees and shrubs as well as a focus on rest areas that can be “best reclaimed by planting natives.”

Commercial, Industrial, and public sites: natives can be used not only to reclaim some of these areas but to screen their unsitely views.

Ecological restoration with natives: the authors point out that “Today, land management agencies and private landowners alike have turned ecological restoration into a thriving pursuit.” More ecological restoration using natives is needed in the future.

Icons help readers identify planting locations

What else makes the book particularly useful? How about icons used for each plant that identifies where it should be planted – drylands, rock gardens, seashore, meadows and prairies, shade, sun, restoration, wetlans and, of course, woodlands – all have their own icons.

Chapter by chapter of excellent information for plant enthusiasts

The authors actually spell out in the introduction how they tackle the task ahead beginning with a dicussion of the science of gardening, starting with the ecology of native plants in their natural environments.

In chapter 2, they provide practical advice for choosing, planting, and maintaining native plants that are best suited for your particular environment. (What more can a beginner native plant gardener ask for?) There are also tips for managing garden invasives.

Chapter 3 tackles the enormous task of providing descriptions of native trees, shrubs, herbaceous perennials, grasses and even some annuals worth considering.

If you’re a gardener in the Pacific Northwest you will want to tap into the authors’ incredible native plant knowledge that is covered in this book.

For more Ferns & Feathers articles on Gardening in the Pacific Northwest, you will want to check out the following posts:

• Native plant plan for a front garden in Seattle

• Understory Gardens aims to bring more sustainable gardens to the west coast

Ferns & Feathers readers already know the importance of using native plants in our gardens. This book simply emphasizes that importance in a part of Canada and the United States that is already inherently blessed with a gardening lifestyle that begs us to protect and restore not only the native plants, but the wildlife that depends on it for survival.

Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest is an essential resource for gardeners to explore how to best use the natural gifts they are provided on a daily basis.

• If you are considering creating a meadow in your front or backyard, be sure to check out The Making of a Meadow post for a landscape designer’s take on making a meadow in her own front yard.

If you are on the lookout for high quality, non-GMO seed for the Pacific North West consider West Coast Seeds. The company, based in Vancouver BC says that “part of our mission to help repair the world, we place a high priority on education and community outreach. Our intent is to encourage sustainable, organic growing practices through knowledge and support. We believe in the principles of eating locally produced food whenever possible, sharing gardening wisdom, and teaching people how to grow from seed.”

About the authors:

Arthur R Kruckeberg (1920-2016) was professor of botany at the University of Washington for nearly four decades. He cofounded the Washington Native Plant Society and authored The Natural History of Puget Sound Country and Geology and Plant Life, as well as prior editions of Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest.

Linda Chalker-Scott is associate professor of horticulture and extension specialist at Washington State University . She cohosts the Garden Professors blog, and her books include The Informed Gardener, The Informed Gardener Blooms Again, and How Plants Work.

Richard G. Olmstead is prefessor of botany at the University of Washington and curator at the University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum.

The book is published by the outstanding, garden-focused Canadian publishers Greystone Books. Visit their website at Greystonebooks.com for a complete selection of their books, including some of the most highly sought after gardening books.

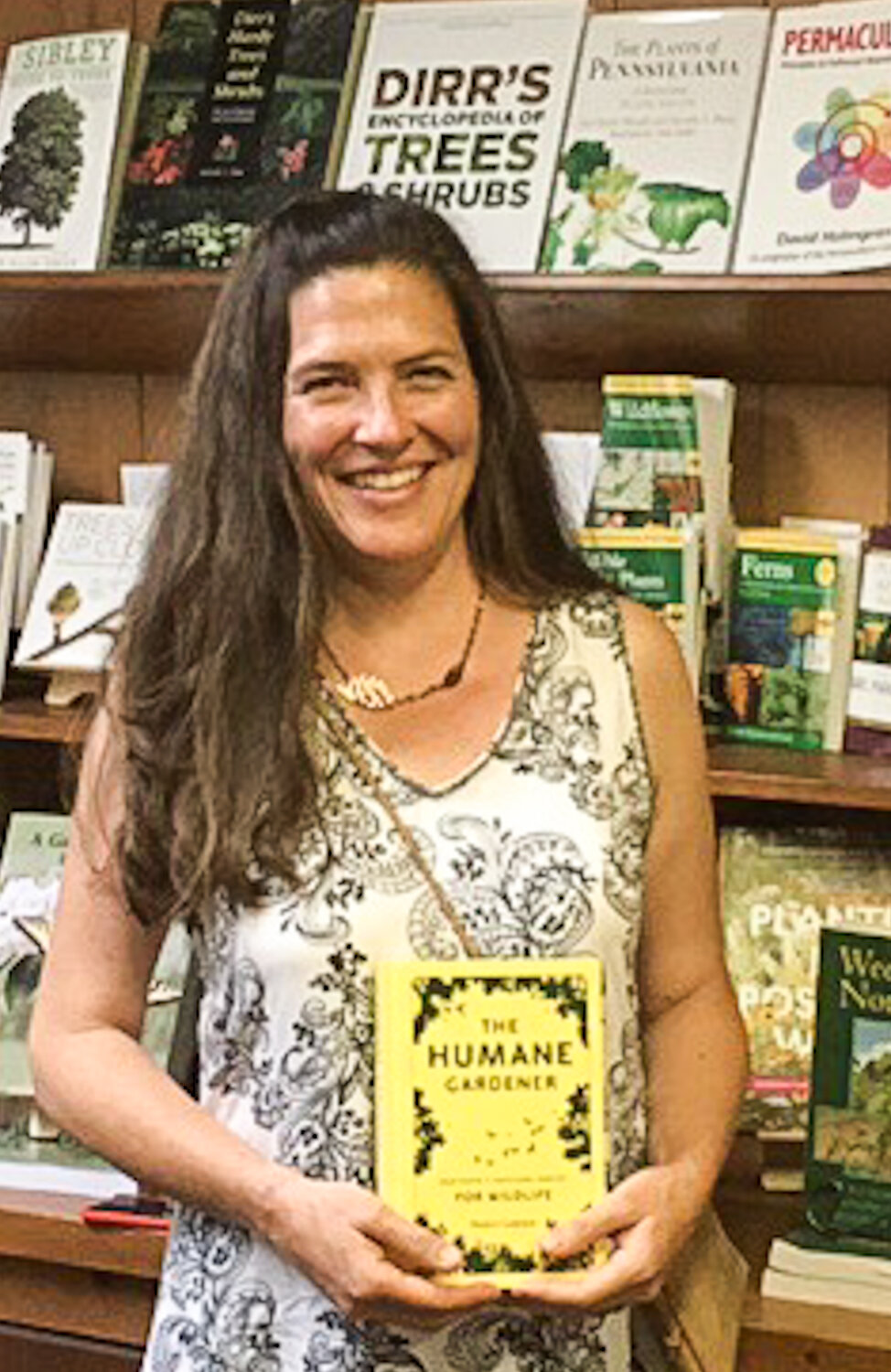

Understory Gardens: Focus on sustainable west-coast landscapes

Alexa LeBouef Brooks is a west coast garden designer looking to convince people that we need a more sustainable approach to garden design in the face of climate change.

Garden designer’s favourite plants for the natural garden

Alexa LeBouef Brooks is changing the world around her, and she’s not alone.

Like so many other people her age working to protect the earth, Alexa recognizes that the environment is at a critical juncture – either something is done soon or we risk losing much of what we have in the not-too-distant future.

The 33-year-old landscape designer is fully aware of the environmental challenges that lay ahead for future generations and the precarious path humans could be facing in the future.

Alexa is part of a new breed of progressive landscape designers taking it upon themselves to reject traditional garden designs and embrace a new, more sustainable garden style – at least in the town she calls home. Her Pacific West-Coast designs specialize in developing a more sustainable, woodland or naturalized gardening approach – hence the name Understory Gardens.

(For more on West Coast garden designs and native plants, be sure to check out my post on Vancouver-Island-based Satinflower Nurseries, Native plants find a home on Vancouver Island.)

Also, if you are interested in native plants, be sure to check out my post on Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest.

That love of woodland and natural garden designs has its roots in her childhood.

“Growing up in the Pacific Northwest my parents often brought me to the mountains or the river and seasides to go camping and exploring. From a young age I found myself in awe of our natural beauty,” Alexa explains.

“I think the development of my style of gardening grew from my desire to always be connected to the natural beauty I spent so much time in as a child. Although I embrace multiple garden aesthetics, the native and natural style of gardening keeps me rooted in the land I call home.”

Inspired by the work of Irish landscaper, author Mary Reynolds

Although her love for natural gardens has its roots in her childhood, Alexa owes much of her garden design approach to the work of famed Irish landscape designer and author Mary Reynolds who, rejected the traditional landscape design methods to focus mainly on restoring the land and habitats. She is founder of the environmental movement wearetheark.org, that encourages gardeners around the world to create more natural, sustainable gardens through the use of native plants.

If you are interested in getting more on the work of Mary Reynolds and her book Garden Awakening, you might be interested in my article Garden Awakening will change the way you garden.

Another landscape designer that has shaped Alexa’s work are the more classic designs of Miranda Brooks.

Although her passion is landscape design, Alexa’s real challenge is about combining beautiful, but ecologically sustainable landscapes for her clients.

Her long list of achievements has helped lead her to starting landscape design in 2018.

Vice chair and landscape designer for the Edmonds Architectural Design Board

Completed Edmonds Community College courses in specialty pruning and design

Member of the Plant Amnesty Gardener Referral List

9 years experience with organic Agriculture and animal husbandry

8 years experience with ornamental Horticulture

Plant Amnesty: Focus on maintaining ecology and environment

Through the excellent work of the Seattle-based, non-profit organization called Plant Amnesty, many of Alexa’s clientele are already aware of the importance of protecting the ecology of the area.

The organization’s focus is to educate the greater Puget Sound area on proper pruning, responsible gardening and land preservation.

“I find that most clients who seek gardeners and designers through Plant Amnesty have a shared interest in maintaining the integrity of our delicate ecology and environment. Even outside of my Plant Amnesty clients, when a potential client sees my business name and website, they are anticipating a particular style of gardening from my work. Most are open to the suggestions I make when designing their gardens and plugging in additional plants to an existing design as well as garden maintenance methods.

“The more I learn about the benefits of using strictly native plants, the more I turn to them,” Alexa LeBouef Brooks.

Designer is turning gardens into works of art

Alexa’s background in fine art certainly helped prepare her for the challenge

“In 2012 I received my bachelor’s degree of Fine Arts and Art History and pursued the art world in my twenties. I have always had my hands in the soil for as long as my memory serves me. I think that is why I enjoy art and art making so much, is because there is a tactile element that requires the use of hands and creativity, while getting a little messy along the way,” she explains.

“Somewhere along the journey I started getting interested in the design element of landscaping. I could use my creative skills on paper to transform beautiful outdoor living spaces. Landscape design has become the perfect marriage of all my interests in the art and landscaping world.”

Along the journey, she is playing a vital role in saving the natural environment and landscapes in her home town of Edmonds, Washington just outside Seattle, where she is the vice-chair for the Edmonds Architectural Design Board.

“I believe all homeowners should be stewards of their land, to preserve and maintain the diverse ecology of surrounding plants and species,” she explains.

Alexa is doing her part to help guide her clients along this path. Education plays an important role in her relationship both with her clients and the environment she creates for them.

“My design process includes an educational element in which I teach my clients about individual plant and seasonal needs. I like involving my clients in the design process because it inspires them to learn more about maintaining our natural environment, and their personal garden is the perfect tool to achieve this.”

I believe the natural landscape of the Pacific Northwest stirs inspiration in people of all ages to maintain its beauty.

She is quick to point out that, “responsible stewardship can also be achieved by creating designs for clients that integrate native and drought tolerant plants as well as plants that attract our resident pollinators.”

Alexa uses her extensive knowledge of the environment and use of native plants to guide her clients.

“I believe the natural landscape of the Pacific Northwest stirs inspiration in people of all ages to maintain its beauty,” she explains.

“It could be as simple as leaving most of the fallen leaves and using it as an attractive mulch for garden beds. Destructive methods include stripping the top layer of mulch and soil using powerful gas blowers and excessive raking. Not only does this negatively impact butterfly larvae populations as well as leave little nesting materials and berries for birds, but you are left with bare soil that does not retain moisture and nutrients for our increasing summer temperatures in the Pacific Northwest.”

Climate change: Awakening a new style of gardening

Alexa is the first to admit that climate change is awakening homeowners, who may have once dreamed for a certain style of garden, into realizing that a new, more sustainable approach to gardening is now needed.

“In the midst of our climate crisis and environmental destruction, Washington’s winters are bringing in more rain and colder temperatures while our summers are bringing in more drought and higher temperatures. What was a temperate climate is slowly becoming more extreme,” she explains.

“One of the biggest challenges we now face are forest and brush fires. Because of our increasing temperatures in the summer, many landscapers are implementing more California natives. The drawback is not all California natives thrive in our decreasing winter temperatures. So, instead of trying to control a shift in our plant hardiness zones, we must adapt and allow our plants to adapt. This, of course, comes with trial and often error. More and more clients are requesting drought tolerant plants in their gardens, and I am happy to oblige.”

(Be sure to check out the full story of Alexa’s Seattle-area garden design, including a list of native plants used in the design.)

Alexa’s favourite Understory trees for Pacific Northwest gardens

Acer circinatum (native Vine Maple) for its spectacular fall color and interesting structure.

Cornus nuttallii (native Pacific Dogwood) for its cascading branching and delicate flowers.

Cornus controversa 'Variegata' (giant Dogwood or Wedding Cake tree) for its gorgeous cake-like layers of branches and delicate variegated color.

Cercidiphyllum japonicum (Katsura) for its fall color and fragrance of leaves that smell like burnt sugar.

Magnolia macrophylla (Bigleaf Magnolia) for its broad leaves that provide a tropical feel.

Alexa’s favourite ground covers for Pacific Northwest gardens

Cornus canadensis (native Bunchberry dogwood) for its seasonal interest from flowers, to berries, to multi color leaves. (For more information on our native bunchberry be sure to check out my story here.)

Frageria chiloensis (native Beach Strawberry) for its fruit, flowers and evergreen interest.

Ophiopogon 'Nana' (Dwarf Mondo) for its hardy evergreen blades that can withstand heavy traffic.

Erigeron glaucus (native Seaside Fleabane) for its spring through fall blooms.

Erigeron karvinskianus 'Profusion' (Fleabane) for its delicate white and pink flowers.

Alexa’s favourite Shrubs for Pacific Northwest gardens

Vaccinium ovatum (native Evergreen Huckleberry) for its edible berries and sculptural element.

Ribes sanguinium (native Flowering Currant) for its vibrant flowers.

Arctostaphylos 'Howard McMinn' (California native Manzanita) for its red bark, bell shaped flowers and silver leaves.

Picea abies 'Pusch' (Norway Spruce) for its hot pink cones and pin cushion shape.

Rosa nutkana (native Nootka Rose), for its rose hips and just to add a bonus, Corylopsis spicata (Winter Hazel) for its winter flowers.

Incorporating natives and non-natives in the landscape

While Alexa strives to incorporate more and more native plants in her landscapes, clients needs often dictate the use of non-natives. In many cases, non-natives are already well established in the gardens.

“My designs meet the clients where they are, and I incorporate many different aesthetics that cater to the clients needs and desires. That being said, I will always see myself as a student in anything I pursue. The more I learn about the benefits of using strictly native plants, the more I turn to them, explains Alexa.

(If you are looking for more information on the importance of using native plants in our gardens, check out my comprehensive post: Why we need native plants in our gardens.

“There is a list of plants that I strictly avoid in our area. These include invasive species that drive out beneficial pollinators, degrade habitat, cause disturbance in the food web, and even chemically alter soil biology. This doesn't even cover genetically engineered plants which is an increasing technology being utilized that has known and unknown consequences. The most important act we can do as gardeners and landscapers is educate our clients on what is appropriate for our area and be cognizant of our watershed, soils and precious species.”

Alexa gives much of her success and knowledge of plants to her friend Bre Moravec.

“My friend and fellow gardener Bre Moravec, owner of Gaia Gardens is the perfect example of this. She goes the extra mile to educate herself to educate others. Because of Bre’s passion she has mentored me and other gardeners, teaching specialty pruning methods and in depth plant species knowledge and identification.”

How Covid changed the way we garden

When asked how important she thought it is for homeowners’ physical and mental health to surround themselves in a landscape they love, and how rewarding it is for her when her clients fall in love with their new gardens, Alexa responded: “It has always been important, but ever since the Covid pandemic it is more important than ever.

“There have been studies that time spent outside, specifically in a more natural setting improves sleep, lowers overall inflammation, enhances blood flow, repairs cells and tissues, and improves electrical activity in the brain. How amazing would it be if we can access this from our backdoor! I love helping my clients transform what was once an uninviting space into a space in which they and their families can retreat to, where it is safe because they know chemicals aren't being used, and they can enjoy all the benefits and pleasures that our seasons bring.

(If you are looking for more information on the importance of being outdoors in nature and in our gardens, you will want to check out my post Why kids need more nature in their lives.

And what does Alexa love most about her job?

“My relationships with my clients and time outside bring me most joy. The most difficult hurdle about this job is probably Washington’s weather. We’re known to get a lot of rain here!

For more information, or to contact Alexa about landscaping, visit her website at Understory Gardens.

If you are looking for more inspiration, you may be interested in Gardens of the Pacific Northwest.

If you are on the lookout for high quality, non-GMO seed for the Pacific North West consider West Coast Seeds. The company, based in Vancouver BC says that “part of our mission to help repair the world, we place a high priority on education and community outreach. Our intent is to encourage sustainable, organic growing practices through knowledge and support. We believe in the principles of eating locally produced food whenever possible, sharing gardening wisdom, and teaching people how to grow from seed.”

Sumac: First signs of fall in the garden

Staghorn Sumac is an excellent addition to the garden both to add architectural interest and provide a food source for birds and animals.

Important food source for birds and other wildlife

It’s early October and the native Sumac is already lighting up the roadsides and welcoming the first signs of fall in the woodland garden.

Along roadsides and escarpments, where this fast-growing native shrub or small tree (grows to about 30-feet high) gets plenty of sun, Sumac lights up with brilliant oranges, yellows and reds.

It’s often the first plant nature photographers focus on when in search of early colour in the fall landscape, and it’s a perfect addition to the woodland garden. Sumac has compound, serrated leaves that are a bright green in summer before taking on its fall cloak.

How did Sumac get its name?

There is no missing the velvety bark on the branches that cover Staghorn Sumac. This velvet resembles the velvet that covers the antlers of male deer (stags) throughout the summer, earning Sumac the name “Staghorn”.

There are more than 30 varieties of Sumac in North America with more native varieties in Europe, Africa and Asia.

Is Sumac a food source for birds and other wildlife?

Not only is Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) an incredibly colourful addition to the woodland, its fall berries, that grow in large clusters atop the shrub’s branches, are also a very important source of high-value food for birds especially migrating birds.

Staghorn Sumac puts out small greenish-yellow flowers that attract pollinators. They grow in the shape of a cone in spring and become the reddish-haired fruit clusters as summer turns to fall.

These hearty fruit clusters, that often remain on the plant well into winter, are vital resources for hundreds of bird species including our backyard favourites like Cardinals, Gray Catbird and a host of woodpeckers ranging from the impressive Pileated to the small Downy and larger Hairy woodpeckers. Add to that list the American Robin together with other thrush species. In a more wooded natural area, don’t be surprised if it attracts Ruffed Grouse and wild Turkeys.

As an added bonus these plants are deer resistant.

Staghorn sumac is dioecious, meaning that it has individually male and female plants.

These shrubs/small trees are extremely hardy, and are both drought and salt tolerant. They prefer a sunny location and dry to moist soil and will not tolerate shade or wet soil. Use these fast growers as an erosion control plant if you have problematic areas.

Where I live, The Niagara Escarpment is the dominant geological feature that cuts through the landscape. The Staghorn Sumac lights up the many cuts through the escarpment and turns the roadsides into sparkling jewels at certain times of day.

Staghorn Sumac is native to the more southern half of Ontario, and eastward to the Maritimes.

Sumac species include both evergreen and deciduous types. They generally spread by suckering, which allows them to quickly form small thickets, but can also make the plants overly aggressive in some circumstances.

There are usually several varieties available at nurseries, but this attractive native is probably all you will need.

Other forms of Sumac

At one of my local nurseries there are three Sumacs listed including the Staghorn Sumac. The others are Fragrant Sumac, and a dwarf variety of fragrant sumac called fragrant gro low Sumac as well as Cutleaf Smooth Sumac.

Cutleaf Smooth Sumac (Rhus glabra Laciniata) is a smaller hardy shrub (hardiness zone: 2B) with finely cut tropical-looking leaves that add texture to the garden. Grown primarily for its ornamental fruit, and its open multi-stemmed upright spreading habit. It lends an extremely fine and delicate texture to the landscape and can be used as a effective accent feature. Click on the link for more information on the Cutleaf Smooth Sumac.

Gro Low Sumac is described as low growing and compact shrub with interesting foliage turning brilliant colors in fall and bright yellow flowers in spring. Makes an excellent ground cover as it tends to sucker, filling in areas quickly. Does well in shade. Click on the link for images and more information on the Gro Low Sumac.

Fragrant Sumac is described as a rugged and durable medium-sized shrub with interesting foliage turning brilliant colors in fall and bright yellow flowers in spring. Tends to sucker, forming a dense spreading mass, attractive for a garden background or for naturalizing, good in shade.

Plant Native Sunflowers for the bees, butterflies and the birds

Our native woodland sunflowers are not only beautiful but important plants for native bees, birds, butterflies and other insects.

A grouping of Woodland sunflowers in their prime light up the edge of a forested area. The sunflowers are a magnet for native bees and butterflies and their hollow stems provide winter nesting habitat for native bees.

Woodland sunflowers are native to Ontario and parts of the United States

It’s not just good looks that make our native sunflowers a must for the woodland garden. Their popularity among butterflies, native bees, birds and other insects makes these tall shrubby plants a popular choice for wildlife gardeners.

In our garden, the multi-flowering, bright yellow Woodland sunflowers (Helianthus divaricatus) grow at the back of the property alongside other meadow-style plants such as Black-eyed susans, New England and Wood Asters. They seem happy to grow beneath our crabapples where they receive mostly dappled afternoon and late afternoon sun.

If you are looking for more information on growing native flowers, you might be interested in reading my comprehensive article: Why we should use native plants in our gardens.

The Woodland sunflower is native to the eastern United States and Canada and can be found along roadsides and on the edge of woodlands and forested areas.

A large grouping of Woodland Sunflowers looking their best backlit against a dark background.

Hardy in zones 3 to 7, they work beautifully planted along woodland edges together with Black-Eyed Susan, Scarlett and Spotted Bee-Balms, and goldenrods. They will thrive and spread quickly in full sun but also do well in partial shade.

Generally these prolific bloomers, that can grow up to 6-feet tall, can be found growing naturally in dry, open woodlands, making them perfect for our woodland gardens.

The tall stems support the 2-inch (5cm) yellow flowers that sport 8-15 petals and a darker yellow centre disk. The flowers bloom from early summer to fall. The self-seeding sunflowers spread by rhizomes accounting for the large colonies often seen growing along forest edges and roadsides.

Besides dividing the clumps every 3-4 years to control spread and maintain the plants’ vigour, these Sunflowers are generally low-maintenance with no pest or disease issues.

A single woodland sunflower growing in our garden. You can see the buds of more sunflowers preparing to bloom.

Our deer have no interest in the woodland sunflowers probably because of the plant’s tough stems and rough leaves that make them less desirable.

Even Walnut trees are no match for the woodland sunflowers.

Without a doubt, they are a favourite of bees and butterflies where they act as a host plant for more than 73 varieties of butterflies and moths as well as a number of other insects that depend on the plant.

In turn, the caterpillars and insects that use the sunflowers as host plants, attract birds that depend on the insects as a source of food.

The Painted Lady, silvery Checkerspot and Gorgone Checkerspot are just three butterflies that use native sunflowers as a host plant for their larvae.

Birds and small mammals can often be seen eating the seeds right off the fading flowers.

Our native sunflowers are also an important plant for native bees that use the plants’ hollow stems for nesting. It’s important not to cut down the plants after flowering to give native cavity nesting bees a safe, warm place to overwinter their larvae. Leave the long stems in place at least until late into spring.

More native sunflowers

• Pale-leaved Sunflower (Helianthus Stromosus) grows to just 4 feet, in sun to part sun conditions in average to dry sandy loam.

• Other native sunflowers include Giant Sunflower (Helianthus giganteus) that grows up to 10 feet in sun to partioal shade in sandy loam.

If you are on the lookout for high quality, non-GMO seed for the Pacific North West consider West Coast Seeds. The company, based in Vancouver BC says that “part of our mission to help repair the world, we place a high priority on education and community outreach. Our intent is to encourage sustainable, organic growing practices through knowledge and support. We believe in the principles of eating locally produced food whenever possible, sharing gardening wisdom, and teaching people how to grow from seed.”

Native Goldenrod: Fall’s golden gift to wildlife gardeners and photographers

Goldenrod blooming in our gardens and along roadsides is a sure sign that fall is not far off. These are important native plants for a host of bees and butterflies that depend on the plants for late summer, early fall food sources.

Goldenrod might be the best addition to your fall garden

It might be common in your area along highways and open fields, but don’t underestimate the benefits of goldenrod in your garden.

This structural plant is not for the weak of heart. Mine stands more than six feet high, stretching up to the sky and, like a neon sign along a deserted highway, announces to every monarch, swallowtail, bee and butterfly in the area to come on over for some good eats. And they are happy to oblige.

In fact, the National Wildlife Federation, pointing to the work of author and biologist Doug Tallamy states: “Tallamy’s studies show that goldenrods provide food and shelter for 115 butterfly and moth species in the U.S. Mid-Atlantic alone. More than 11 native bee species feed specifically on the plants, and in fall, monarch butterflies depend on them for nectar to fuel their long migrations. Even in winter, songbirds find nourishment from goldenrod seed heads long after the blossoms have faded.”

If you are looking for more information on growing native flowers, you might be interested in going to my comprehensive article: Why we should use native plants in our gardens.

Goldenrod growing along the edge of a field bringing its fall early fall colour to the landscape and garden.

Does Goldenrod cause hay fever?

Let’s get this straight right off the bat – goldenrod does not cause hay fever – that would be ragweed. Goldenrod’s pollen is too heavy to be blown in the wind, while ragweed pollen takes to the air at the mere hint of a slight breeze.

It’s also important to note that not all Goldenrod is aggressive in the garden. It’s also probably a good time to note that Goldenrod is available in many forms – all beneficial to local pollinators.

We’ll get into all the different types and which ones might be good for your garden later, for now let’s just admire this native plant for what it is – a pretty, yellow magnet for bees, butterflies and other insects.

I just let it grow in my front and back gardens, not really worrying too much about its aggressive tendencies. But that’s just me.

Flower photographers love Goldenrod in the garden

I find it perfect for photography because, not only do the yellow masses of flowers form a great backdrop for the butterflies, the plants are so tall that I really don’t even have to bend over to get shots of the butterflies, insects and birds. Now, that’s a real bonus.

For more on photographing flowers in your garden, please check out my comprehensive post on Photographing flowers in your garden.

A native bumblebee works the goldenrod in our backyard as it comes into bloom.

Let’s take a closer look at this fall performer.

Goldenrod is actually a common name for a number of plants in the sunflower family within the genus Solidago. In fact, there are around 120 species of goldenrods native to the Americas, northern Africa, Europe and Asia.

In North America, about eight of these species are used as garden plants where they happily set roots in full sun to partial sunny areas in almost any average to below-average, well-drained soil. These herbaceous perennials, that are pretty much pest free, can grow from about 1.5-6 feet tall with a spread of 1-3 feet.

In very fertile soil, you may have to stake them to stop them from falling over when their heavily flowering tops get too heavy to stand on their own.

Although there are a number of hybrids that have a more compact size or flower more heavily, don’t bother with them. Stick to the native varieties and you will likely have fewer problems, help native wildlife more and sleep easier at night knowing you’re not introducing some weird, aggressive new plant to our already compromised natural environment struggling to fend off all the cultivars we have introduced over the years.

Goldenrod fills many roadsides in late summer and fall creating a tapestry of subtle fall colours.

Some native varieties to consider include:

Blue-stemmed goldenrod (Solidago caesia) is one of the more rare Goldenrod species and sports the common latesummer and fall bright yellow flowers. The plant gets its name from its arching purplish stems. This particular Goldenrod is noted because it not an aggressive spreader and produces good cut flowers. Plant it along with Smooth Blue Aster and New England Aster for some spectacular fall colour and pollinator action. Blue Stemmed Goldenrod is hardy from zone 4 through 7.

Autumn Goldenrod (Solidago sphecelata), is the native plant that horticulturalists like to use to make various cultivars from primarily because of its compact size. Autumn Goldenrod tends to stay to within a foot or two with its arching stems and plumes of yellow flowers.

Showy Goldenrod (Solidago speciosa) lives up to its name with its dense clusters of small yellow flowers that grow in a pyramidal- or club-shaped column, sitting atop the 1-5-foot tall reddish stems. It is considered one of the showiest of Goldenrods.

Sweet Goldenrod (Solidago odora) This is a more compact native variety that reaches two- to four-feet. You’ll find it growing naturally in dry, sandy, open wooded areas thickets and ravines. It’s distinguishing feature is its anise-scented leaves and the fact that it is another goldenrod that is considered less aggressive in a garden environment. It is a clump-forming, easy to grow, low maintenance plant that reaches up to 4-feet high and attracts birds, bees butterflies and hummingbirds. It’s found growing naturally in meadows or open woodlands.

White Goldenrod (Solidago bicolor) you guessed it, rather than sporting the typical yellow flowers, this goldenrod likes to show off white blooms.

Wrinklelfeaf or Rough Goldenrod (Solidago rugosa) if you have a moist area in the garden, this three- to five-foot goldenrod is the one to use. It’s distinctive narrow, toothed, rough-surfaced leaves and rough, hairy stems earned the plant its name.

Even as cut flowers the Goldenrod looks great in the garden but be careful, they’ll still be attracting the bees.

It’s time for a little gold in the garden

Just about the time the Black-eyed Susans get into full swing, the Goldenrods come along and add even more gold to our landscapes. They ride that gold right into late fall and are still adding to the beauty of the garden when the snow falls and forms a little blanket atop the browning flower clusters.

Throughout fall, the goldenrod and asters form a perfect combination of warm golds and cool blues along our roads and in meadows creating incredibly textured landscapes throughout Ontario and into the north-eastern parts of the United States.

The activity these plants create among the remaining bees, butterflies, hummingbirds and other backyard wildlife is reason enough to grow our own patches of these lovely native plants. We let ours grow wild where the seeds land, but these plants can be tamed and grown in the back of gardens with great success.

If you don’t already have them in your woodland/meadow garden, put them on your list for next year.

You won’t be disappointed.

Monarda and Cardinal flowers: Native reds Hummingbirds can’t resist

Monarda and Cardinal flower are two native reds Hummingbirds can’t resist. Both have similar tube-like flowers that are perfect for hummingbirds and other pollinators.

A female Ruby-throated Hummingbird works the bright red Bee Balm.

Add these two fine reds to your garden and enjoy the pollinator party

Hummingbirds love reds and the combination of Monarda and Cardinal flowers prove just too irrisistable for them.

You could almost say these native red flowers combine the natural sweet flavours that keep our hummingbirds, bees and butterflies drunk with excitement over the natural abundance of their favourite food. But, that might be pushing the whole red wine thing a little too far.

In our garden, the Monarda begins to bloom in early July and the hummingbirds quickly add them to their daily feeding rounds. I notice, however, that the Cardinal flowers – growing just a few feet away – are not far behind the Monarda. Within weeks the area beside our patio will be a haven for hummingbirds looking to fill up on the sweet natural nectar that these two native reds provide.

If you are looking for more information on growing native flowers, you might be interested in going to my comprehensive article: Why we should use native plants in our gardens.

Our feeders, too, are nearby but given the choice, Hummers will prefer to visit the more natural nectar sources. It’s a good idea to keep this in mind when you are trying to attract hummingbirds and other garden pollinators. Provide their natural food and chances are they’ll visit more often and stay longer.

If using native plants to feed birds and pollinators in your garden interests you, you might want to check out this post on feeding birds on a budget.

Create a natural stage for Garden photography

In addition, the more natural stage for the hummingbirds and butterflies will turn you into a master when in comes to garden photography. There’s nothing like the male Ruby-throated Hummingbird, with its red throat, working the bright red Monarda and scarlet Cardinal flowers. Set up your camera and telephoto lens nearby, grab a glass of your own favourite “red” and just wait for the hummingbirds to arrive. It shouldn’t take long before you are rewarded with some great photographs.

How to grow Bee Balm (Monarda)

Monarda (Monarda didyma) often referred to as Bee Balm is a member of the mint family (Lamiaceae). It joins Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), that features light lavender to pinkish-white flowers, in the Lamiaceae family that counts 16 species native to North America.

(Go here for my full story on Wild Bergamot )

Monarda can really put on a show. Blooming for up to 6 weeks through mid summer to early fall on tall (up to 4 feet), sturdy square and hollow stems, these attractive perennials have deep roots with shallow rhizomes that account for its spreading habit. It can form large drifts in your garden creating a magnet for hummingbirds and other pollinators including those cool Clearwing hummingbird moths, native bees including bumblebees and, of course, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

Like it’s sister, Wild Bergamot, the Monarda flower is actually a cluster of 20 or more flowers (fistulosa) arranged in a round head. The fistulosa (tubular or pipe shapes) make them ideal for long-tongued insects, bees, moths and butterflies to feed on. The plants’ nectar is so sought after by insects that you may notice holes carved out of the flower stems where “tongue-challenged” insects have bore through to get at the nectar.

The plants easily take to a garden and are at home growing along other garden plants, in a sunny meadow-style planting or as specimens in sun, part-shade. Bee balm actually prefers average soil (too rich and you are liable to have tall, lanky plants that don’t hold up well on their own.) Powdery mildew can be a problem if the plants are grown in a wet, humid area without good airflow.

Keep the plants watered but not wet and you’ll be blessed with a great show all summer.

• If you are considering creating a meadow in your front or backyard, be sure to check out The Making of a Meadow post for a landscape designer’s take on making a meadow in her own front yard.

How to grow Cardinal flowers

Cardinal flowers prefer a more wet environment than Monarda so growing them side-by-side will be difficult. Ours grow several feet apart and through hand watering I am able to keep the Cardinal flowers’ feet in more moist soil. Our Cardinal flowers have found a home on the outside edge of a yellow magnolia so also get get less sun than the Monarda plants.

Take a moment to check out my full feature on growing the native Cardinal flower.

Cardinal flowers are considered short-lived perennial but by spreading the seed in your garden, you can enjoy the flowers for years to come. Try placing the spent flower heads atop the soil in a moist part of the garden and you should be blessed with more and more flowers each year. They grow on long spires that can reach up to 4 feet. The flowers bloom as they make their way up the stalk.

In conclusion: Two reds can make a right

Planning your patio should involve more than where the best seating options are, unless, of course, you’re planning the seating options around the best wildlife viewing spots. By making an effort to plant attractive native plants such as Cardinal flower and Bee balm that attract hummingbirds, butterflies and birds, your patio or deck transforms from just a place to sit and entertain, into a place to be entertained.

As summer heats up, I can’t imagine a better time than being outdoors on the patio or deck with my favourite red and a couple of feathered friends dropping by on regular visits.

Solomon’s seal is solid choice for the woodland or shade garden

Solomon’s seal’s arching branches reveal the dangling cream flowers that highlight the spring woodland garden.

Is Solomon’s seal a native North American wildflower?

Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum), with its elegant arching stems that rise up in clumps through the forest floor, deserves a prominent place in any woodland garden.

This unassuming, eastern North American native plant is completely at home in the woodland or shade/semi-shade garden where it forms patches of attractive plants that spread – always under control – through underground rhizones.

The Graceful arches of the Solomon’s seal reveal the drooping creamy flowers dangling from beneath the leaves.

Like a lovely hosta, Solomon’s Seal is more of a textural plant that might not steal the show with colourful flowers in early spring or even striking berries. Instead, this native wildflower quietly reveals itself in early spring as individual, zig-zag arching stalks that will eventually stretch out to 1-5 ft. long, begin to emerge from the soil. Solomon’s seal has alternate, smooth leaves that grow up to six inches long and about three inches wide with parallel veins. A waxy coating on the round, smooth stems creates a blue-green colour.

How to use Solomon’s seal in the landscape

In the landscape, the Solomon’s seal are best used as an understory plant that helps create height with its arching stems and attractive leaves.

Eventually, clusters of up to one to four white or off-white tubular-shaped flowers dangle beneath the lance-shaped leaves. The flowers grow to about half-inch to 1-inch long.

A variegated form is available that adds a little more interest to the plant if the all-green variety just doesn’t cut it for you.

Although the plant is attractive throughout the spring and summer, its fall foliage really shines in the woodland garden. The arching stems turn a bright yellow as they age and become tattered over time.

For more on using Solomon’s seal in the garden, take a moment to read my article on using textural plants in the landscape.

How to grow Solomon’s seal

Like many native woodland flowers, Solomon’s seal will grow best in moist, loamy, woodsy soil in light shade. Don’t be afraid to cover them in late fall with fallen leaves to protect the clumps during freezing temperatures and eventually build up the soil around the plants.

Solomon’s seal arching branches show off the cream flowers following a spring rain.

In our landscape

We have had both the more common green native plant as well as the variegated form in our front woodland garden for several years where it happily grows through the ground covers creating interesting form for visitors walking up our garden path.

Do Solomon’s seal attract pollinators?

Because it is another early spring bloomer, Solomon’s Seal is an important plant for pollinators ranging from a variety of native bees, including (Bumble bees, digger bees) that gather nectar and pollen from the white or creamy flowers.

Do Solomon’s seal attract hummingbirds?

In addition, Ruby-throated hummingbirds take advantage of the early flowering plants as a source of nectar flying beneath the leaves to sip from the druping, tubular flowers.

Solomon’s seal shows its early fall colours in this image. The native plant is a highlight in the fall garden as yellow slowly envelops the entire plant.

What birds eat the berries from Solomon’s seal?

In late summer, woodland birds will zero in on the resulting blue berries providing nourishment to the birds that help to spread the seeds throughout the garden. The berries are eaten by Eastern Bluebirds, Hermit Thrush, American Robins, Veery and Wood Thrush. In addition the native wildflower attracts insects, which, in turn, help to attract insectivorous birds looking for a quick meal.

I would like to say that the native plants are deer resistant, but they are not. Don’t be surprised if you go out in the morning to find many of the plants munched by our four-legged friends. Deer predation is no reason not to grow these native plants. Instead, think of them as a little natural food for our forest friends.

How to grow sunflowers

Looking to grow sunflowers this season? Here is a guide to growing them in your landscape as well as in containers, including growing tips on the massive, single-flowered variety as well as the smaller, multi-flowered varieties.

Are sunflowers difficult to grow?

Everyone loves sunflowers and growing them is generally simple.

The majority of annual sunflowers (Helianthus annuus) ask for nothing more than lots of sun and water combined with average soil. Generally speaking, the more sun they get the larger the flower will be and the stronger the stems will grow to hold up the large flowers. Fertilizer is unnecessary – maybe some added compost – but mulching will help to hold moisture in the soil. Sunflowers have a very deep tap root that is more than capable of finding water several feet (up to four feet) below ground.

Woodland gardeners, however, may find that their gardens’ lack of sun requires a little more effort and planning to ensure success. Adding to a lack of sunny areas, if deer are regular guests in your garden, there’s a good chance you will also have to take extra steps to get the plants to adulthood.

The rewards of planting sunflowers are many: Fun cheery flowers from summer into the fall and even longer if planted in succession; a tap root that helps to bring nourishment from deep in the soil to the surface; and, especially a natural food source for birds and other backyard wildlife that put sunflower seeds very high on their nutritional needs. (Check out my complete story on providing birds with natural food sources.)

Growing your own sunflowers is great for the birds, bees and butterflies, but don’t overlook the fun you will have photographing them as they brighten up your garden when they begin to bloom. For my comprehensive post on taking a creative approach to photographing sunflowers and ten tips to capture them go here.

A dwarf sunflower in early May grows in one of our new containers.

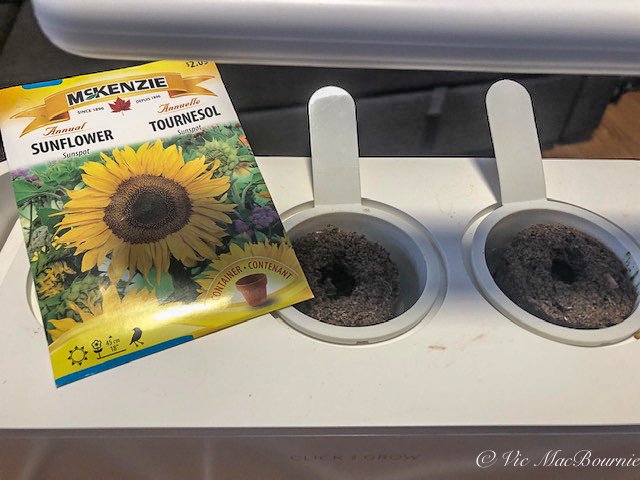

In this article, I’ll take readers step by step – over the course of a spring and summer – through the process of growing sunflowers and bringing them to maturity both in containers and in the landscape. I’ll be starting some early under lights in our Click and Grow (link to my article) complete with its automatically timed grow lights and self watering system.

We will also be growing sunflowers in small peat containers that will later be transplanted into the landscape. Other seeds will get their start later in spring in our outdoor raised planters away from hungry deer and still others will be directly sown in our large outdoor planters. Finally, I’ll plant a number of seeds directly into our garden and do my best to get them to maturity despite an abundance of deer and other fauna that visit the garden.

For more on the value of sunflowers in our gardens, check out Fields of Gold: Sunflowers and Goldfinches.

Do deer eat sunflowers?

Let’s start with our number one question: Do deer like to eat sunflowers? Anyone with a bird feeder knows that deer love sunflower seeds, but we are more concerned with them eating the plants rather than the flower head and seeds when it matures.

Deer love the tender shoots of sunflower when they first emerge and will nip them off until the stems begin to get more robust and they thicken and grow too tough to be appetizing. If we can get the plants to this stage, the deer tend to leave them alone for the remainder of the growing season.

I’m sad to say that I did not have much luck getting the plants to this stage before squirrels, deer and rabbits decided to dine on them. (I think part of the reason for this is that I started to grow the plants inside too early and the green plants stood out in the otherwise brown landscape just a little too much. This spring I’ll wait another couple of weeks to put them out into the garden when there is more for the wildlife to dine on.)

Sunflowers offer perfect opportunities for garden photography looking as good death as they do in bloom.

(Early June Edit) It’s early June and so far we have had mixed success. The dwarf sunflowers that were grown in the Click and Grow lighting system did well. They grew fast and I was able to get them into several containers by mid May where they continued to grow. Three of these dwarf varieties have bloomed, but it wasn’t long before chipmunks and squirrels went in for the kill and decided the flowers were there for their lunch.

Two small sunflowers (dwarf varieties) growing in a new large container were attacked by squirrels and decapitated but luckily I was able to get a flower from it. (See second and third images above.)

• I planted a multi-flowered variety in a large container in the front garden that was doing very well until a squirrel or chipmunk decided to use it as a swing. The plant was healthy and about 3-4 feet tall with a large bud forming getting ready to flower before it was broken off. I thought growing it up through a trellis should provide a little protection and give it support. But in the end it was broken off before flowering.

If a sunflower bud is broken off will it regrow a new one?

Unfortunately it is unlikely that a sunflower will regrow a bud once the main one has been broken off. Even if the stem is alive and appears to be doing well, once the bud has been broken off or removed, the chance of flowering is unlikely. If it is a clean break, and you get it early, or if the bud is broken but still hanging on, you may be able to save it by taping it up with a gardener’s tape.

July Edit: Forget everything I wrote directly above about regrowth after the stem has been broken. Our multi-flowering sunflower suffered several bud-stem breaks from squirrels or chipmunks, but it now has 7-10 sunflower buds on it. So, to answer the question “If a sunflower bud is broken off will it regrow a new one?” the answer is YES they can. Sunflowers, especially multi-flowering varieties, can regrow buds after the main leader has been broken off. The image above is an example of the plant in flower.

What are the best sunflowers to grow?

There are many different sunflowers we can grow including a perennial native wildflower and an assortment of annuals. When it comes to annuals, there are basically two types – single and multi-flowering. The single-flowering sunflower sports a large (sometimes greater than 12 inches) flower on a tall, stout stem that can easily reach 8-16 feet tall.

The multi-flowering form combine several flowers usually consisting of a main flower with smaller secondary ones on a stem that can reach 6-8 feet high but is more often 4-6 ft.

One annual cultivar that is popular is the everblooming sunflower from Proven Winners called Suncredible Yellow that flowers on a heavily-branched plant with blooms that are about 4 inches across and do not need deadheading to continue blooming. The plant grows to about 3 feet tall and blooms longer than similar sunflowers lasting well into the fall.

A lovely stand of native perennial sunflowers growing wild in a nearby field.

The native perennial (zones 3-7), Woodland Sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus) is a lovely multi-flowering wildflower that will attract bees and many butterfly species including Checkerspot and Painted Lady. The flower is much smaller than the traditional annual variety. It can be planted along woodland edges in full sun or partial shade along side Black-Eyed Susan for example and, unlike the annual plants, is deer resistant. (Check out my post on why we should be using native plants in our garden and how they help birds and other predators.

Our woodland sunflowers are beginning to show buds and I expect flowers to begin emerging in the near future. This will be the second year the woodland sunflowers will be in the garden, so I am hoping for a good show this year.

Large sunflowers planted in large clumps can be impressive and extremely important for both pollinators and birds.

Last spring, I planted the native perennial woodland sunflowers in a back part of our garden and am looking forward to seeing how they perform this year.

But, we are here to talk about the wide assortment of annual flowers ranging from the massive flowering types, to the medium ones good for both containers and in the landscape, as well as smaller dwarf varieties that are ideal for containers.

All are excellent choices, but consider how best to use them in your landscape.

A Click and Grow kit that includes an experimental kit to allow gardeners to grow whatever plants they like including native widflowers as well as sunflowers.

What are the best sunflowers for containers

If you are planning to use the sunflowers in containers, use a dwarf variety for best results, unless the container is quite large. Remember that the root systems of sunflowers are extensive and include a large and aggressive tap root. (There is a list below of some of the better multi-stem and dwarf varieties.)

The dwarf variety that I started in the Click and Grow have done well and made it into the garden containers in mid May. Most flowered quickly before the beginning of June and are now providing our chipmunks and squirrels with early snacks.

The big boys are probably best at the back of the garden or used as a large windbreak or privacy screen in a long line of plants. If you are planting them in this way, it’s always a good idea to stagger the plants to give them room to grow and air around them to circulate to prevent mildew and fungus problems. Leave at least six inches between plants (more is probably better) and make sure they get all-day sun or close to all-day sun.

The mid-size sunflowers are an excellent choice providing the sunny cheerfulness that only sunflowers can provide, but in a more manageable size coming in at 5-6 feet in height.

Here is a short list of some of the better sunflowers.

A closeup view of a sunflower.

Tall single-flower sunflowers

Skyscraper: Sunflowers can reach heights of up to 12 feet and produce 14-inch petals.

Sunforest Mix: Rises from 10-15 feet.

American Giant: This sunflower can reach up to 15 feet and a flower face that grows up to a foot tall

Russian Mammoth: Expect heights of 9 to 12 feet with a huge flower face.

Sunflower seeds placed inside the soil from the Experimental kit and ready to be grown through the systems automatic timed grow lights and self watering system.

Smaller, dwarf sunflowers include:

Sundance Kid: This bicolour red and yellow flower grows from between one to two feet tall.

Little Becka: Is a pollenless sunflower that sports red and yellow petals and grows between one to two feet tall

Pacino: This muti-flowered plant has a bright yellow face and grows to between 12-16 inches.

Sunny Smile: Another plant in the 12-15 inch range with bright yellow petals and a dark-brown centre.

Coloured sunflowers include such show stoppers as Moulin Rouge with its solid red petals, Terracotta sporting cream and orange petals, and Chianti: dark purple petals and dark centre.

If you are on the lookout for high quality, non-GMO seed for the Pacific North West consider West Coast Seeds. The company, based in Vancouver BC says that “part of our mission to help repair the world, we place a high priority on education and community outreach. Our intent is to encourage sustainable, organic growing practices through knowledge and support. We believe in the principles of eating locally produced food whenever possible, sharing gardening wisdom, and teaching people how to grow from seed.”

Celebrate No Mow May along with the butterflies, birds and bees

The No Mow movement is sweeping the world after getting its start in Britain. It is now being picked up by environmental groups, cities and towns and individual homeowners looking to do their part to help native flowers and fauna.

The No Mow May movement is picking up steam around the world. We can all play our part by just doing less.

Plantlife gives birth to No Mow May movement sweeping the world

Turns out we have permission not to mow our grass in May.

Not only do we have permission, some very important people, environmental agencies and lovable tree huggers are actually encouraging us not to cut the grass. Instead, just let it go and see what comes up. They promise we might even be pleasantly surprised.

Turf grass has long been considered a waste of time and money, but ever increasing information points to extensive turf grass being extremely detrimental to native fauna from insects and pollinators to mammals, amphibians and reptiles that are losing habitat at an alarming rate.

Need proof? Check out my earlier article about why we need a whole lot less grass in our lives.

We can thank some folks in Great Britain at Plantlife for this little grass-cutting reprieve. In their own words: “Plantlife is a British conservation charity working nationally and internationally to save threatened wild flowers, plants and fungi . We own nearly 4,500 acres of nature reserve across England, Scotland and Wales. We have 11,000 members and supporters and HRH The Prince of Wales is our Patron.”

Talk about working to save native plants, Plantlife can boast some pretty serious achievements.

For example, Plantlife, with its HQ in Salisbury and field staff spread across Britain including national offices in Wales and Scotland, was instrumental in the creation of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation and is a member of Planta Europa, a pan-European netwok of more than 60 wild plant conservation organizations.

So Plantlife might have led the way, but now environmental groups, cities, towns you name it are jumping on board to declare May as No Mow Month to kick off spring and provide a healthy boost to native flowers and grasses, and the bees, butterflies, birds and other wildlife that thrive in more natural landscapes.

• If you are considering creating a meadow in your front or backyard, be sure to check out The Making of a Meadow post for a landscape designer’s take on making a meadow in her own front yard.

Letting areas of the yard go back to nature can result in native wildflowers springing up in places you would never expect.

Cities and towns take No Mow May to new levels

Here in Ontario, for example, a town outside Toronto, East Gwillimbury, is actually encouraging residents not to cut their grass to “ help support pollinators during this crucial spring period as they are seeking their first food sources of the season such as dandelions and other flowers typically found in lawns. This movement is important as research indicates a mass extinction of insects is underway. Of particular concern in recent years, is the decline of the bee population.”

Residents are asked to avoid mowing lawns until June with the goal of preventing disturbance of overwintering insects and amphibians that may be burrowed or hiding in leaves and lawns, and to increase food sources to pollinators.”

And, if that is not enough, they are turning it into a competition where residents sign up for the challenge, pay $5 and receive a lawn sign to “show neighbours” they are supporting No Mow May.

All the donations are going to the David Suzuki foundation Butterfly Way. The Butterfly Project has expanded to hundreds of communities throughout Canada with more than 1,000 volunteer Butterfly Rangers who, together with recruits planted pollinator patches in thousands of yards, gardens, schools and parks in 2021.

Greenpeace gives No Mow a boost

Even Greenpeace has jumped on board to promote the No Mow May Challenge. In an article on its website, Greenpeace points to why a flowering meadow is so much better than a well-mown lawn.

Greenpeace states: “By compiling several European and American studies in a meta-analysis, the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières has revealed that lawns create manufactured ecosystems with low biodiversity, a condition that worsens as the intensity of mowing increases. Lawns that are mowed more frequently are linked to a decrease in the number of invertebrates and have less plant diversity, while the presence of pests and invasive species goes up. We have every reason to think twice about our obsession with perfectly manicured lawns.”

Bee City USA joins in the No Mow May fun