Why digging up or picking wild flowers threatens our natural areas

Is picking or digging up wildflowers and other plants from the wild wrong. According to experts in the field, it is almost always the wrong thing to do. Even collecting seed from rare plants can be a bad decision, especially if approval is not sought from the landowners in advance. Ferns and Feathers asks the experts what they think about collecting plants from the wild and what are alternatives.

Is it illegal? It’s certainly almost always unethical

We all like to save money, but digging up wildflowers is not the way to do it.

Not only is digging up plants on public property including parks and conservation areas likely illegal in most states and provinces, more importantly it’s an attack on our natural ecosystem that is already facing threats to its survival.

Even if it’s not illegal, in most situations, it is not the ethical thing to do.

You might ask: ‘what’s the harm of taking one or two plants from acres and acres of plants?’

Consider that every year more and more people discover the joys of being outdoors and experiencing nature. In fact, more than 500 million people visit public lands each year in the United States alone.

Imagine the devastation to the national forests if just a fraction of these people choose to dig up small trees, shrubs and rare flowers to take back home with them for their gardens, where the flora most likely die a slow death in the wrong soil, in the wrong lighting conditions and without the forest ecosystem that played an important role in their survival.

Public lands provide us with places to relax and unwind and offer incredible inspiration for our own woodland gardens. (For my full article about using natural woodlands as inspiration for our woodland gardens, click here.)

If you are interested in exploring the world of shade gardening further, you might like my recent post on The Natural Shade garden.

Respect wild areas and leave any wildflowers where they grow. Harvesting a tiny amount of seeds can sometimes be acceptable if approval is first obtained from the landowners.

It’s important to remember, however, that the real purpose of the plants, trees and shrubs in our parks, forests and public lands is not to provide a beautiful landscape. The prime purpose of these landscapes is to provide and sustain life in many forms – from the smallest insects to the largest mammals, from lichens and mosses and rare plants to monster-size redwoods.

Ontario’s 36 Conservation Authorities main purpose, for example, is not to provide outdoor areas for the public to go for walks and enjoy nature (although they are very successful in this endeavour), their real purpose is to maintain the vitality of our watersheds and protect peoples’ lives and property from natural hazards such as flooding and erosion. Click here to go to the Ontario Conservation Act.

“Sometimes this drive to do the right thing is met with some knowledge gaps, especially when we are new to gardening with native species. Our actions need to be viewed collectively, and we must ask ourselves: If everyone did this, would this action be okay. ever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.”

These public lands play an important part in helping to clean our air and water and provide some of the last habitat for the protection not only of our endangered wildlife but the plants that are often intertwined with the survival of this very wildlife. They provide homes for rare host plants for threatened butterflies, nesting habitat or food for endangered birds or vital to the survival of native bees.

Every time a visitor digs up a plant, a small tree or a shrub they threaten this ecological web and weaken an already fragile ecosystem.

If that’s not enough of a reason, consider that stealing from nature can land you in big trouble.

Removing anything from Canada’s national park is strictly forbidden. Technically, you are not even allowed to pick flowers.

Hummingbird on Cardinal flower.

The following is taken from the National Park’s system general regulations:

10. No person shall remove, deface, damage or destroy any flora or natural objects in a Park except in accordance with a permit issued under subsection 11(1) or 12(1).

11. (1) A Director-general may issue a permit to any person authorizing the person to take flora or natural objects for scientific purposes from a Park or to remove natural objects for construction purposes within a Park.

(2) A permit issued by the Director-general under subsection (1) shall specify the kind and amount of and the location from which flora or natural objects may be removed and the conditions applicable to the permit.

(3) Where natural objects are removed for the purpose of constructing other than a public work within a Park, every person on removal of such natural objects shall pay to the superintendent the sum of twenty-five cents for each cubic yard of such natural objects or fraction thereof.

12. (1) The superintendent may issue a permit to any person authorizing the person to remove, deface, damage or destroy any flora or natural objects in a Park for purposes of Park management.

(2) A permit issued by the superintendent under subsection (1) shall specify the kind and amount of and the location from which flora or natural objects may be removed, defaced, damaged or destroyed and the conditions applicable to the permit.

But let’s face it, not all situations are the same. It can be a very complex discussion, especially when you get out of national parks and other public lands.

Is it okay to dig plants, collect seed and remove small trees and shrubs from areas that are threatened by increased farming, planned subdivisions or urban areas that are being taken over by non-native vegetation and being destroyed by neighbourhood teens using them as their own playgrounds? Maybe a small woodlot is being taken over by a group of dog owners using them as their personal dog park. As a result, the dogs are ripping up areas of endangered wildflowers, maybe even rare orchids or wild lupines.

Action to save these plants, it could be argued, certainly needs to be considered.

Ferns and Feathers tapped into experts in the field for their opinions on this important discussion.

Kristen Miskelly, a biologist with specialty in the botany and ecology of southeastern Vancouver Island and a co-founder of Saanich Native Plants, is quick to point out the dangers we face as the environment continues to be threatened by climate change and other, man-made, highly destructive actions.

“The natural world needs our help more than ever and people are trying to do their part by growing native plants,” explains Miskelly, who teaches at the University of Victoria.

“Sometimes this drive to do the right thing is met with some knowledge gaps, especially when we are new to gardening with native species.

“Our actions need to be viewed collectively, and we must ask ourselves: “If everyone did this, would this action be okay.

“Digging up wildflowers is almost always not the best approach and, in fact, can be very harmful. Some of the negative side effects to ecosystems include disruption of soil leading to colonization of non-native invasive species and reducing prospective generations of the given plant by reducing propagules reaching the soil.

“Furthermore, hand dug plants from the wild are not as successfully transplanted as nursery- grown.

Most ecosystems are already seriously degraded and often just shadows of their remnant range and species abundance and diversity. It would be difficult to rationalize depriving them more for our personal gains in a garden setting.

“With so many serious threats to the natural world associated with harvesting or digging up plants, there are very few cases where this approach is warranted.

Are there times where plants can be salvaged?

According to Miskelly there are times when digging plants to save them from destruction makes sense.

“Inherent Indigenous harvesting rights and salvaging from an organized plant salvage from a development site are good examples of when plant collecting is okay,” she explains.

“So, what is the best approach?

“There is an array of native plant growers who are growing in a sustainable and ethical way. Support these growers, by purchasing your plants or seeds from them.” she explains.

“You can go a step further by questioning nurseries about their growing protocols and what steps they take in making sure their methods are sustainable. When you initiate or grow your garden in this way, you can not only benefit nature, but also lend your support to a green economy.”

Reyna Matties from Ontario Native Plants echoes similar concerns over the harvesting of native plants.

“Rescuing plants from sites makes sense when an area is getting developed or altered. In other cases, it is much better to grow your own plants or support a local nursery that is sustainably sourcing seeds and growing local species (like Ontario Native Plants),” she explains.

“Harvesting plants from wild places is quite taboo to any ecologically minded individual due to the potential damage it can do to the habitat for the plants and wildlife that call it home. It is like someone coming to your yard and pulling up your plants. They are not yours, so better to not take them. There are so many other ways to get plants.”

Reyna explains that anyone who harvests seed should always follow sustainable seed practices by taking only a small peercentage of a parent plant’s seed. Even if you are taking just a few seeds, she explains that you “also want to make sure you have permission from the land owner to be taking seed from that specific location.”

“By sustainably collecting seed, you are actually helping plants proliferate, which is a great thing,” she explains.

In conclusion

Taking plants from national parks, nature reserves and conservation areas is absolutely the wrong approach. Rescuing plants from threatened areas can be done under the guidance of experts through a local wildflower group or conservation group. Taking a small percentage of seeds with the approval of a land owner can be a legitimate approach, as well.

The best, method of collecting rare or highly sought after flora is to purchase it through a reputable native wildflower seller. These outlets exist throughout the United States and Canada, and can be found either through the World Wide Web or, better yet, through local wildflower associations or your local garden club.

As an affiliate marketer with Amazon or other marketing companies, I earn money from qualifying purchases.

Beginners guide to backyard wildlife photography

A beginners guide to backyard wildlife photography exploring how to attract birds and animals to your woodland garden, how to use get close to them and what camera systems to consider to capture images of birds, insects, butterflies, and mammals.

Tips to creating a backyard photo studio

Photographing wildlife in your backyard can be one of the most rewarding experiences imaginable. Forget about travelling to far off places to get exceptional images, with a little planning outstanding images are possible right in your own backyard.

Colourful birds and butterflies, fascinating insects, amphibians and reptiles are just a sampling of some subjects just waiting to be exposed.

I am lucky enough to have encouraged and photographed a wide range of mammals like rabbits, raccoons, chipmunks, squirrels, foxes, coyotes and, of course, deer to my garden.

The photographic possibilities are endless. And, even if you are an experienced photographer, using your backyard as a photographic studio will give you the opportunity to hone your skills so that you can take advantage of situations in the field or on expeditions to far-away locations.

So, the first task is to get subjects in front of the camera lens?

By creating an environment in our yards that attracts a wide variety of wildlife; closely observing their habits and movements around the yard; learning how the light plays on our garden throughout the day; and finally, purchasing the best camera, lenses and other photographic equipment to help us get the images, it is possible to capture images you may never have thought possible.

A close approach to this fawn was possible because of the animal’s inherent sense to stay perfectly still counting on its ability to blend into the natural surroundings.

Create the environment for successful photography

The goal of creating a backyard wildlife studio is to attract as many different species as possible and to present them in their most natural environment.

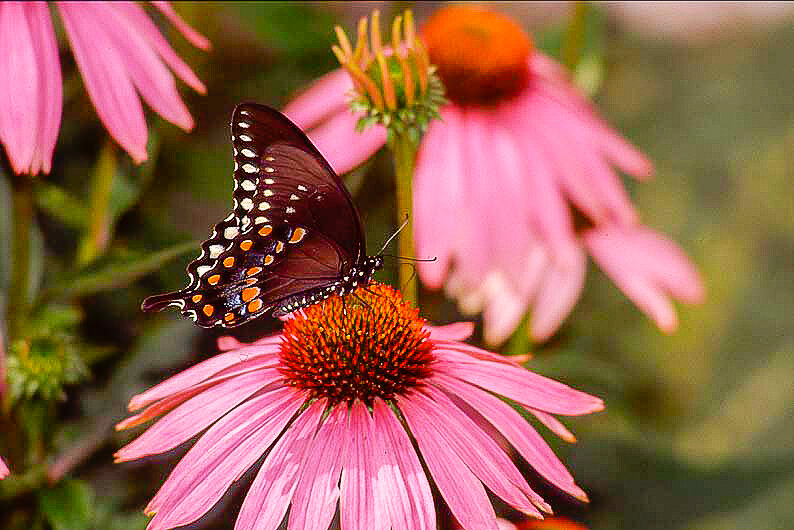

We have been regular proponents of using native plants (to your region) in the garden. In fact, this website is filled with articles extolling the virtues of using native plants. They are vital to native pollinators, birds depend on their seeds and berries for food as well as the insects and caterpillars native plants attract. Native plants are critical for the survival of so many of our native butterfly larvae…

Here is another important benefit to using native plants in your garden – photographs of the insects, butterflies and birds that depend on these plants appear much more natural when photographed on a native plant species than they are on a hybridized version of the plant or, even worse, one that they would most likely never feed on in the wild.

So how do we create these mini backyard studios?

Start by creating islands of native flowering plants. If you are just starting to create your backyard photo studio, try to choose a sunny site for the best flowering opportunities. A butterfly garden is always a good place to start, especially if you have children. A butterfly garden provides a perfect opportunity to encourage children to begin exploring the natural world in a fun way. Just make sure you provide both host plants for the caterpillars as well as nectar producers for the adults.

“Even if your yard is more or less barren, there are steps you can take to begin landscaping it for wildlife. Rewilding an existing backyard by planting islands of native plants will encourage a huge number of insects, pollinators and birds. Add a pond, even a small one, to encourage an even greater abundance of fauna.”

Good host plants for a butterfly garden include milkweed for our beloved monarch butterflies; plants of the carrot family including dill, fennel and Queen Anne’s Lace for the Black Swallowtail; violets are the host plant for the Great Spangled frittilary, and legumes are host plants for spring and summer Azure and other blue butterflies in addition to silver spotted skippers. Other host plants of note include Black-eyed Susans and Asters (Silvery Checkerspot, Northern Pearl Crescent), Pussytoes and Pearly Everlasting (Painted Lady butterflies).

Another area of the garden could be focused on heavy berry producers that attract insects in the spring- and summer-flowering periods followed by birds later in the season feeding on the berries.

Remember to consider the sun when situating these plants. If you enjoy photographing birds in the morning while you are enjoying your cup of coffee, you will need to locate the berry-producing bushes in an area that gets morning sun. If you prefer more dramatic lighting in your images, such as back lighting, use the morning sun to create a backlit image. The evening sun will then provide a warm, more direct light on the berries and the birds feeding on them.

In shady areas, consider planting woodland natives and spring ephemerals.

Even if your yard is more or less barren, there are steps you can take to begin landscaping it for wildlife. Rewilding an existing backyard by planting islands of native plants will encourage a huge number of insects, pollinators and birds. Add a pond, even a small one, to encourage an even greater abundance of fauna.

Creating these wildlife island plantings will help you to focus on more manageable, smaller areas of the garden rather than being overwhelmed trying to decide how to design the entire backyard. These garden islands are not so large that they could not be created in a single weekend. Creating your gardens in this fashion is also an ideal way to garden on a budget.

My wife and I are blessed to live close to a natural conservation area with acres of woodlands, streams and ponds, but we have worked hard to create a natural environment in our backyard to take advantage of the abundance of fauna and flora that already exists around us.

A good example of creating a mini photo studio by attracting backyard birds with a birdbath to capture interesting close up images. In this instance, I was set up in the Tragopan blind just a few feet from the blue jay. However, once the birds get accustomed to your presence, this type of imagecould have just as easily been taken without the blind. Consider setting up at least one birdbath near where you regularly enjoy your morning coffee.

The value of water in your wildlife studio

Everyone loves the idea of a pond in the backyard, but not everyone wants the potential work that they can bring.

When it comes to photographic opportunities, even a small pond and waterfalls is difficult to beat. Not only will birds regularly visit the location, but a host of insects, reptiles and amphibians will either be regular visitors or decide to make it their home.

All this makes a backyard pond and mini-waterfalls the ideal outdoor photographic studio.

A small pond is not difficult to install and can easily be accomplished in a weekend with a helper. Making it look natural is more difficult and requires research and preferably plenty of large rocks, even boulders to create a natural looking pond you will be happy with in the long term.

I installed a pond and a small waterfalls in another home we owned and it was truly an enjoyable experience watching it mature. Frogs, tadpoles and even a small contingent of fish called it home and caring for it was relatively simple. I would highly recommend considering a pond if you think it’s right for you and your family.

In our current home, we have chosen to install a small bubbling rock around a dry river bed. The solar-powered bubbling rock is not as successful in bringing in a variety of wildlife as a naturalized pond, but the running water attracts birds and mammals who use it use it as one of their many water sources in the garden.

A red squirrel gets a drink in the DIY reflection pond made from a rubber shoe tray.

Consider creating a reflection pond

There is an option, however, for those who feel they don’t have the time or desire for a backyard pond, but still want to capitalize on the tremendous photographic opportunities that water brings.

Consider creating a reflection pond in your yard.

A small, natural-looking reflection pond may not encourage reptiles and amphibians to your yard, but it could provide a natural studio to photograph them if they already exist in your yard.

These simple-to-construct reflection ponds can be the source of some of your best backyard images. They are usually built as shallow (a few inches deep) large tray-like structures on legs or even placed on a table with natural materials such as stones, pine needles and moss at one end where birds, squirrels and chipmunks are encouraged to go so that the photographer can capture both the animal and its reflection in a natural scene.

Natural material such as mosses, stone and even delicate wildflowers can be added to create the ultimate photo studio. If the reflection ponds are kept small, they can be moved around the garden to take advantage of lighting conditions. They can also be redesigned regularly to take advantage of seasonal changes. In spring, for example, a flowering tree branch can become the focus of the reflection pond. In fall, viburnum berries and colourful leaves add a splash of colour.

By tucking bird seed in various crevices, you can attract a variety of backyard birds, squirrels and chipmunks. A small toad would look perfectly natural tucked up against the moss and even a friendly snake would look good among the rocks reflecting in the water.

A natural, lichen-covered tree branch on the bird feeding pole entices a nuthatch to pose for the photographer

A simple set-up for birds

It should come as no surprise that a lot of the great backyard bird photographs you see on instagram and elsewhere are actually carefully set-up involving props, possibly lighting techniques and food to entice the birds.

That’s not to say the images are not great and getting them is easy. Most often, a lot of preparation and care have gone into the creation of these photographs.

It goes without saying that a very important part of your backyard bird and wildlife studio involves bird feeding stations.

It’s a good idea to have several placed in strategic locations throughout the yard set up for different types of birds, different lighting conditions and backgrounds.

I primarily use a single bird feeding station that can accommodate several styles of feeders as well as perches. The feeders change, depending on the season and type of birds expected to be visiting at any one time. Other feeders around the yard are dedicated to specific species such as hummingbirds and orioles, but the main feeding station is the primary focus when it comes to bird feeding and photography.

It’s located in an area where it gets morning back lighting or side lighting (depending where I am set up) and afternoon direct sun. I can choose my background depending on where I choose to set up – it can be blue sky, the soft-focus of distant trees or the more focused look of nearby crabapple trees. All the backgrounds can work depending on lighting conditions.

The feeding station is built around a Wild Birds Unlimited single pole system with two steel hooks for hanging the main feeders; a spike on the top to accommodate seed cylinders; several smaller clip-on feeders for meal worms; berries and special treats; a tray to catch seed and provide a feeding platform for birds who prefer to eat off platforms; a steel stylized perch perfect for hanging smaller feeders; and an attachment that can accommodate a small branch to be used as a natural perch.

The natural branch attachment makes the bird-feeding station particularly valuable to the photographer. The simple cylinder that slides into the main pole is large enough to accommodate any branch you want to use whether that is flower-laden from the Crabapples or Redbuds when they are in bloom, an evergreen bough left over from Christmas decorations or a branch covered in clumps of berries in the fall.

DIY branch and suet feeder

One of my favourite photographic stages is using a branch that has been drilled out in several places to accommodate suet or bark butter. It can be hung on the pole to create a very natural perch and feeder for woodpeckers, nuthatches, chickadees and other backyard favourites.

These suggestions are just a few of the many possibilities you can experiment with in your backyard wildlife studio. Some photographers, for example, enjoy setting up old garden tools as perches for bird photography to create memorable garden images. I am currently working on getting a series of images of birds on a peace sign as my ode to hippies, love and peace in the garden. Use your imagination and have some fun creating natural, or simply fun garden images of the wildlife in your garden.

Tools of the trade to capture striking images

Photography can become a very rewarding hobby allowing you to unleash your creative expression or simply a tool to document your garden and share an image or two on with friends on Facebook or Instagram.

One thing is sure, however, photography as a hobby can be addicting and making the wrong decisions can get costly, fast.

The number one mistake most photo enthusiasts make is to think the only way to get the images they want is to invest in longer and more expensive telephoto lenses and cameras that can fire off 100s of photos in seconds.

Nothing could be further from the truth, but longer lenses and faster motor drives in the hands of an experienced photographer can make all the difference.

Chasing elusive birds and animals in the field is likely to require the best lenses and cameras to capture memorable images, but setting up in your backyard for a photo shoot of birds and mammals that are more or less familiar with you and don’t see you as a threat, requires a different set of tools many of which are simpler and certainly less expensive.

My Tragopan Photographic blind set up in the garden.

The secret behind some of the best images

One tool that has improved my backyard photography and, more importantly the enjoyment of it, is not a camera or a long lens. It’s not a flash or even a high-priced tripod.

It’s a photographic blind.

In my case, it’s a dedicated photographic blind made by Tragopan. The U.S.-based company is making outstanding, high-quality products specifically for photographers. This is not a hunting blind that can be used by photographers, it’s designed and built for serious photographers. In fact their whole line of blinds and products are built for photographers and bird watchers in mind.

So what makes the photographic blind so valuable to backyard birders and photographers?

My one-person blind allows me to get extremely close to wildlife without disturbing their natural habits. It allows me to get outstanding images on a regular basis without investing in expensive cameras and extreme telephoto lenses. This close approach means that an inexpensive 80-200mm zoom can do much of the work that would normally require the use of a much more expensive 400mm lens valued upwards of $8,000 Cdn..

But allowing the photographer a close approach is not the only benefit a photographic blind offers.

Sitting in a blind has to be one of my most enjoyable experiences in the garden. By quietly sitting and simply observing my surroundings, I am able to get a much deeper appreciation of the animal and bird interaction in the garden. The red squirrels carry on as if not a care in the world. They may even know or, at least suspect, that I am in the blind, but their defences come down and they begin to act more natural, allowing me photographic opportunities that probably are not possible if it were not for the blind.

More timid birds and animals are much more likely to accept the blind than they would if I were sitting in a chair nearby. Photographing larger, or more skittish animals like fox, deer and even rabbits can really be improved with the use of a blind.

By no means do you need to go out and purchase a photographic blind. A garden shed can stand in as a shed, or even a window overlooking your garden can become a working blind much in the same way as a dedicated photographic blind.

However, the convenience of being able to move the blind around the yard to take advantage of the lighting conditions and the subjects you want to photograph is a real bonus of the dedicated blind. In addition, the fact the blind offers 360 degrees of photographic possibilities and the ease of setting it up and taking it down, should make a dedicated photographic blind high on the list of more serious backyard photographers.

The tools of the trade: Cameras, lenses and other necessities

The discussion around what camera and lenses should I buy is, as you may have guessed, very much dependent on budget and skill level, and your commitment to photography as a serious hobby.

I can speak with authority only on the cameras I use on a regular basis and the tools I use to capture backyard images. Among the tools I highly recommend is a good tripod and monopod as well as a polarizer to cut glare on water and off of leaves.

Rather than discuss the ultimate camera lens combination, it’s probably more helpful to break it down generally to beginner, intermediate and advanced camera systems that can be used to capture garden wildlife images, from the smallest insect to larger mammals that wander into your yard.

I like to consider myself an advanced amateur when it comes to photography. My current equipment consists of four cameras plus a very heavily used smart phone.

Two of the cameras are digital 35mm SLRs (DSLR) (one old model and the other an even older model), a high-end point and shoot model with limited lens coverage (approximately 28mm-105mm ), and a more recent purchase of a “bridge camera” that straddles the compact point-and-shoot market and the DSLR market.

The “bridge camera” looks and feels like a 35mm camera accept that it does not have interchangeable lenses. Instead, the lens that comes with it is designed for the camera body and offers a wide ranging yet powerful 26X zoom (the equivalent zoom for 35mm of about a 22mm wide angle to a 580mm extreme telephoto.) It also has a very good macro feature that allows for closeups of flowers, friendly insects, amphibians and reptiles.

The bridge camera sounds perfect for all levels, right? Well not really, but more on that later.

Go with what you’ve got

The best camera, so the saying goes, is the camera you have with you. A valid statement but on many occasions that’s my iphone. It’s always in my pocket and gets pulled out regularly for plenty of images. However, it’s definitely not my first choice when it comes to wildlife photography unless I want to show the animal in its environment.

Most smartphones do allow you to zoom in closer to your subject if necessary, but the more the image is magnified the more it is degraded. A simple finger pinch on the screen is often all it takes to move in closer. If it’s all you have, it can be used to capture a usable image.

Pros and cons of the high-end point and shoot

First up is my much-loved Fujifilm X10. It’s a very compact camera that fits nicely in my pocket. It’s the camera I usually take with me if I’m going out expecting to take typical images where I want high-quality and convenience without the need to magnify a subject whether it’s wildlife or a distant scene.

This mid-priced point-and-shoot, like most in its class, takes exceptional images including closeups, but does not have a long enough zoom range to make it effective as a wildlife camera. It is certainly more useful than the smartphone when it comes to these types of images, but not quite enough range to get close to birds and smaller animals. Butterflies and other insects are easily within its macro-range capabilities.

Until this spring, it would have been the camera I choose to carry with me when I was going out in the backyard for my morning coffee. It’s capable of capturing lovely garden scenes, larger mammals in their environment and excellent closeups. It also has numerous capabilities including creating lovely black and white images or dialing in classic Fuji films such as Provia for portraits or Velvia for nature shots with a punch of colour.

Point and shoot: In conclusion

If you already own a good point-and-shoot camera try to master the features it offers. The convenience of its compact size and the quality of images it is capable of providing make them a useful addition to your camera bag. A useful camera for capturing garden scenes, butterflies, friendly birds and possibly insects, but not one you would want to count on to capture more distant birds and mammals.

Using a photographic blind to get in close will certainly help to get usable images, but there are better choices.

If you have one, use it. If not, I would not purchase one with wildlife photography in mind.

Pros and cons of the Bridge Camera

The “bridge camera” (in my case the older model Pentax X5) has many of the bells and whistles necessary to get exceptional images of wildlife both in their environment, if shot with the wide angle lens, and close-ups with the extreme telephoto part of the lens.

If macro is your thing, it will focus extremely close to capture the smallest insects, butterflies or flowers. It also has a screen that pivots so that you can use the camera close to the ground without having to lay flat on the ground to get the image.

It’s an important feature now found on more and more higher-end cameras and is particularly helpful for older folks who are no longer able to get up easily from the prone position, or for just shooting close to ground level.

All of the major camera manufacturers and many of the lesser-know manufacturers offer Bridge camera models.

Bridge cameras’ secret weapon is their lens, which exceeds almost anything you could purchase for a DSLR with interchangeable lenses.

To get the equivalent lens on a DSLR would be extremely costly and heavy. Most bridge cameras offer at least a 20-times zoom range and some go up to 50 times zoom. At the maximum zoom, the magnification on a typical bridge camera zoom lens is equivalent to a 500mm or more on a DSLR, with the longest extending to more than 1000mm.

Although the cameras come with impressive anti-shake features, hand holding any lens with such a high magnification would require a tripod or monopod to guarantee a sharp image.

This image compares the compact Fujifilm on the left, the DSLR with 300mm lens in the centre and the bridge camera on the right.

Sounds perfect right? So what’s the problem?

If the quality of the image is a critical factor for you, the bridge camera results might fall short. Essentially, a bridge camera is actually a compact camera in a bigger, more full-featured camera body with an impressive zoom lens.

What does this mean? It means the sensor in a bridge camera is usually the same size as a typical compact camera’s sensor. As a result, high-quality enlargements, or excessive cropping of the digital image would compromise the image quality.

DSLR with 50mm lens compared to the bridge camera with its massive wide angle to telephoto zoom shows the extreme compactness of the bridge camera considering its ability to get in close to subjects.

Like so much in life, it’s all just another compromise.

In addition, most cameras that rely on an electronic viewfinder can be frustrating to use because of the delay between pressing the shutter and the photographer regaining use of the camera’s viewfinder (offically referred to as shutter lag.) This is not problematic in many photographic circumstances if the subject is more or less still in the frame, but if the subject is moving, the delay makes capturing successful images more difficult.

I am sure that some bridge cameras are better than others and admit that I have no experience with other camera manufacturers, so I suggest you give the camera a good workout in the store before purchasing it. Ask if you can take it outside and try photographing moving targets before you sink a lot of money in a camera that may be more frustrating than useful.

That said, my Pentax X5 bridge camera will be my go-to camera this year when it comes to coffee on the patio most mornings. It will also join me in the camera blind as my second camera to photograph birds and animals at a distance. Its convenient size, wide zoom range and capability of shooting multiple frames per second will make it an invaluable tool to in the photographic blind.

This fox image was taken with a 400mm lens without a blind.

The DSLR for the discriminating photographer

For years, the DSLR has been the mainstay for serious wildlife photography. A full-featured DSLR with a couple of high quality telephoto zoom lenses will result in the highest quality images possible.

Once some basic skills are mastered, the intelligence packed into these cameras combined with excellent autofocus capabilites, means capturing impressive images of wildlife in your backyard is almost a guarantee.

More recently, very high-quality mirrorless DSLRs are proving to be the camera’s of choice for wildlife photographers. Sony and Olympus have become players in the mirrorless models. Be sure to check out these offerings if you are serious about getting into backyard wildlife photography.

Getting into the DSLR or high-end mirrorless camera models all come with a hefty price tag and a camera/lens combination that many casual photographers would agree is too large and too heavy to carry around – even if it is only in our backyard.

There are alternatives to investing heavily in a high-priced, fully featured DSLR with long, fast telephoto lenses or expensive zooms.

Remember the benefits of the photographic blind? By creating the ability to get in close to wildlife, the blind will enable photographers to get high-quality results without the expense of purchasing long, fast expensive lenses.

Consider purchasing a used DSLR. There are many available as photographers upgrade to full-sensor, feature-packed models. In addition, used zoom lenses are also readily available.

A 70-200mm zoom is a good starting point, but a zoom that gets to the 300mm range is a better option for bird photography.

If you think backyard wildlife photography is something you might want to explore at a higher level, consider investing in a 300mm F4 lens combined with an autofocusing 1.4 teleconverter. The combination will give you a relatively fast 420mm lens (actually more like a 600mm lens if the crop factor is taken into consideration).

Without going into great detail, it’s a very nice combination that gives you all the magnification you are likely to need to capture birds in your garden.

It’s a combination that I feel extremely lucky to have in my arsenal. The older style Pentax 300mm autofocus lens with a Tamron 1.4 converter is a combination that works nicely whether I’m sitting in my photographic blind or just enjoying a coffee in the backyard with my camera beside me on a tripod.

The combinations are endless in the DSLR market. You could, for example, invest in a 400mm F2.8 for about $8,000, but I’m thinking that might be better invested in the installation of a pond and waterfalls, a photographic blind or any number of more inexpensive lens-camera combinations.

But that’s just me.

In conclusion

This article is aimed primarily at beginner photographers who want to capture images of backyard wildlife, primarily birds and small mammals.

While photographing backyard wildlife has its challenges, they are no where near as challenging as capturing images in the field. By creating mini photo studios, like natural habitats that attract large numbers of wildlife to specific areas of your garden, reflections ponds and well-thought-out bird-feeding stations with photographic perches, the backyard photographer can create a favourable photographic environment. By using photographic blinds – either existing sheds or commercial blinds – a close approach to backyard wildlife is easily achieved.

In addition, with patience backyard wildlife can be trained to accept our close approach. By regularly sitting quietly in favourite photographic areas throughout the garden, intimate wildlife images are attainable.

Taking advantage of these opportunities allows backyard photographers to focus on capturing wildlife images without having to purchase the most expensive equipment available. For some, who are not interested in capturing award winning wildlife images on a regular basis, a good point and shoot camera may be all they need.

It’s more likely, however, most of us want to capture high-quality images that we can share with our friends on social media like Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. This is where a bridge camera can really deliver. Images will be missed as a result of the camera’s inability to deliver in all circumstances. With patience and practise, impressive images are certainly possible with these cameras. In fact, improvements are making these cameras more desirable with each new model release.

In conclusion, the bridge camera is an excellent choice for beginner photographers looking to explore wildlife in their backyards. If, in the future, you want to step up to a DSLR, the bridge camera becomes a good backup camera for the times you don’t want to bring out the larger and heavier glass.

Finally, photographers who want to take their hobby to new heights, can consider investing in a starter DSLR that provides all the necessary features of an SLR without the added expense of a fully-featured model. A good zoom lens in the 100-300mm will give you access to the majority of images in the backyard environment.

If photography becomes a passion, you can always trade up to better cameras and a fast 300mm or 400mm telephoto lens.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. This page contains affiliate links. If you purchase a product through one of them, I will receive a commission (at no additional cost to you) I try to only endorse products I have either used, have complete confidence in, or have experience with the manufacturer. Thank you for your support. This blog would not be possible without your continued support.

Best plants and shrubs to attract birds naturally and save money

Putting up a bird feeder and hoping for the best might not be the most successful approach to attracting the greatest varieties of birds to our yards. Many birds are primarily insect- or berry-eating birds and will not readily come to your feeders. Consider adding these native plants, shrubs and trees to ramp up your birds.

Beyond the Bird feeder: Best plants to feeds birds naturally

Attracting birds to your yard with a host of feeders is a great way to experience our feathered friends, but the ultimate goal is to create a natural backyard bird-feeding garden that attracts a greater variety of birds and does it more efficiently and for less cost.

That’s not to say we put away the feeders completely. Our feeding station, for example, provides countless hours of enjoyment. It’s daily entertainment I can’t imagine ever living without.

But, let’s face it, feeding backyard birds with commercial seed gets expensive, fast.

If you’re like me, both the look of the feeders and their quality are significant factors in the decision to make a purchase. But the real cost of feeding birds is the weekly or monthly seed costs that keep adding up. Specialty seed, suet, meal worms … the choices are endless.

These concentrated locations where the birds feed can also be a magnet for unwanted visitors to our garden such as an abundance of rats and mice. Best to keep them at bay.

And, let’s not forget the troubling fact that seed-eating birds make up only a small percentage of the bird species that might visit our yards. Despite the high costs and great troubles we go through to feed the birds, we are really missing out on a large segment of the bird species who put seeds lower on their list of favourite foods. A garden or areas of the garden dedicated to attracting birds naturally is an excellent way to experience a greater variety of birds in their natural habitat.

Cardinal in crabapple tree on the lookout for a caterpillar to bring back to the nest.

Ten simple steps to attract birds naturally

Design food islands throughout your garden

Plant native, berry producing shrubs and trees that provide food in summer, fall and winter

Ensure you have a selection of native flowers that attract insects and supply birds with seeds

Eliminate pesticides to save insects for insect-eating birds

Build a wood or brush pile in a corner of your yard

Ensure there are several sources of water available including on-ground pools

Create safe habitat for nesting birds with evergreen and thorny shrubs

Allow areas of the garden to go wild to maximize foraging areas for insect-eating birds

Allow fruit to rot to encourage more insects for birds

Slowly move away from a reliance on commercial feeders and bird seed.

In this post, I’ll take a deep dive into how we can create a natural, backyard bird-feeding garden, to keep the birds exploring our backyard long after most of the store-bought bird feeders and expensive seed are gone.

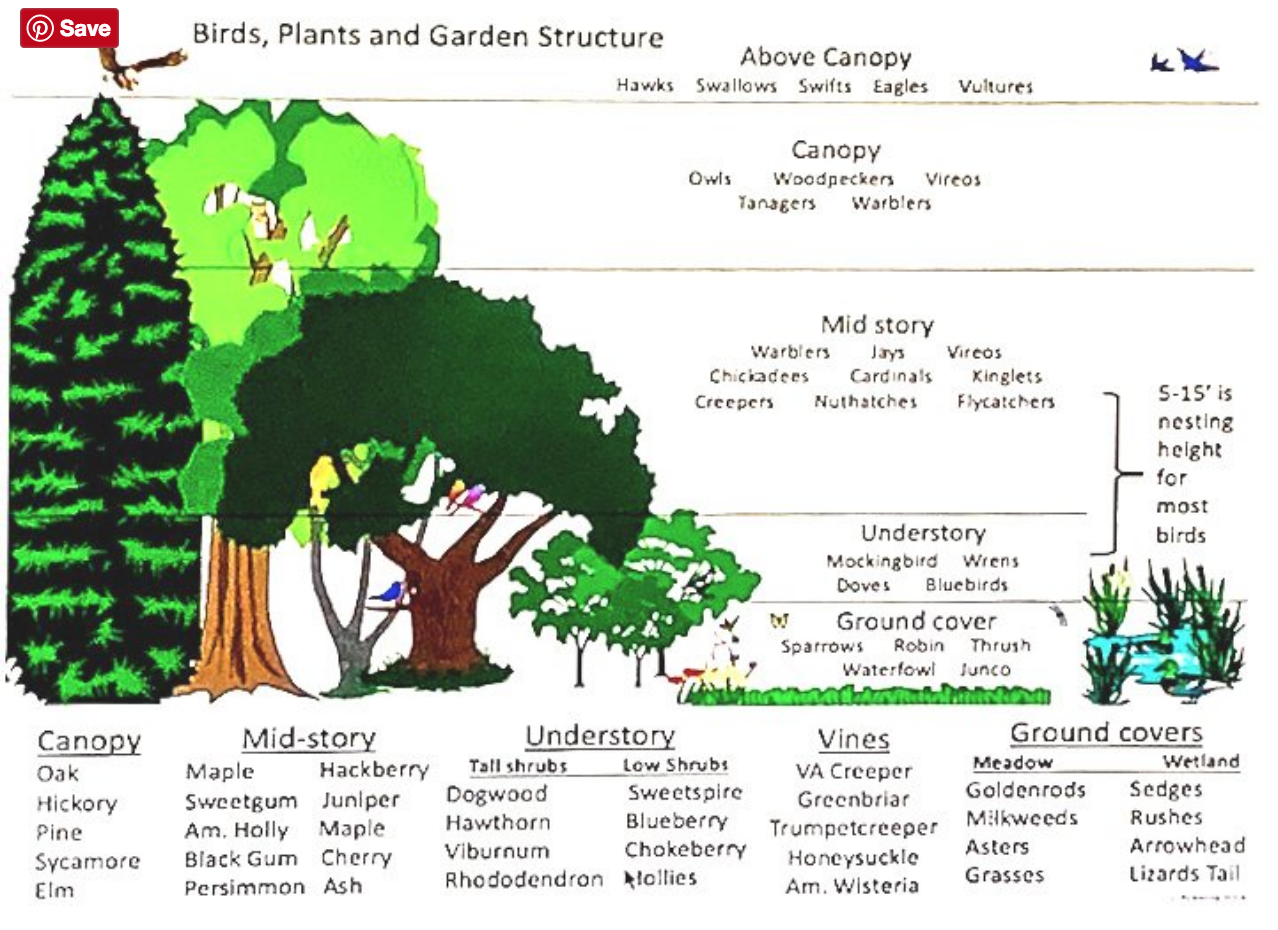

This excellent poster was created by Justin Lewis and is best viewed on a tablet or desktop.

Convincing birds to come to our yards for reasons other than a large cylinder of sunflower seeds involves a multi-faceted approach that may require several years of garden design planning focusing on creating natural habitat, including islands of fruit, nut and seed producing trees, shrubs and flowers that serve a variety of bird species from warblers to woodpeckers. Fruit-bearing shrubs such as viburnums and serviceberries can be supplemented with seed-bearing flowers such as Black-eyed Susans, sunflowers and Asters. Of course there is an oak tree, dogwoods and evergreens in the mix for nuts, berries and nesting habitat.

Deciding on the best trees, shrubs and flowers for our natural backyard bird-feeding garden will depend a lot on where you live, the size of your backyard and how dedicated you are to creating a natural backyard bird feeder.

This post, however, will help to get you started by listing many of the best trees, shrubs, vines and flowers birds use as food sources, and what birds depend on these sources for food.

Ten best shrubs and trees to attract birds

Serviceberry (Amelanchier) Zones 4-8, Every natural bird feeding garden needs a serviceberry. Two or three are even better. I think at last count I had four growing throughout our woodland garden. What makes the serviceberry so important for birds is its early summer yield of delicious deep red almost purple berries. These provide an early feast for birds either just before or during the nesting period. A favourite in our garden of robins waxwings, orioles, woodpeckers, chickadees, cardinals, jays mourning doves, vireos and finches as well as red squirrels and chipmunks. The early spring flowers (early May in our area) attract an abundance of insects which birds are also attracted to as a food source. For more information on serviceberries, check out my earlier story here.

Beautyberry Bushes (Callicarpa Americana) Zones 5-8, If these shrubs provided no value to the birds, I would still grow them in my garden, they are that nice. But it’s their incredible purple berries that grow in clusters close to the stem of branches that make them such attractive little shrubs and is the draw for birds to your garden. These bright purple fruits are attractive to several birds that might not be regulars to your feeders including Mockingbirds, Robins, Brown Thrashers and Northern Bobwhites.

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) Zones 2-7 is a suckering shrub or small tree that grows to between 3 and 19 feet and produces flowers in racemes followed by its fruit that can range from bright red to black. It is found naturally in the northern half of the United States and across southern Canada. Although the shrub plays host to tent caterpillars, it remains an important food source for native birds. For bird lovers, the tent caterpillars are an added bonus. The fruit of the chokeberry ripens from July through to October but doesn’t drop to the groun, instead remaining on the branches throughout winter providing a winter food source for up to 70 species of birds.

American Cranberry Bush (Viburnum Trilobum) and other viburnums zones 2-7 The American cranberry is a mid-size shrub (8-10 feet tall and wide) with its white clusters of spring flowers and stunning rusty red fall foliage is impressive in itself, but it’s the berries on this viburnum that make it shine. Viburnums can be grown as a shrub or small trees and is available in a number of species. Watch for, among others, robins, bluebirds, thrushes, catbirds, cardinals, finches, waxwings to visit your viburnums.

Blackberries (Rubus spp) If you have a corner of the yard you don’t mind giving over to the birds, the blackberry (although considered invasive in some areas) is an excellent choice. The thorny plants provide some protection for nesting birds and because blackberries begin fruiting in late spring and early summer, they provide a good food source during the breeding season. You can expect various warblers, orioles, tanagers, thrashers, mockingbirds,, catbirds and robins, among others to visit your blackberry bushes.

The Flowering Dogwood is a beautiful native addition to any garden but its real superpower is how many birds love to eat its berries, including Eastern Bluebirds.

Dogwood (various Cornus species) zones 5-9 Dogwoods are an obvious choice when it comes to feeding birds naturally. Although they are best known to humans for their early spring blooms, the birds are drawn to the many varieties for their abundance of high-fat content. Popular choices include the pagoda dogwood (Cornus Alternifolia), Flowering dogwood (Cornus Florida), and red twigged dogwood (Cornus Baileyi.) It is said that more than 40 types of birds feed on dogwood berries including bluebirds and other members of the thrush family, woodpeckers, catbirds, thrashers and mockingbirds.

Elderberry Sambucus zones 4-9 This fast-growing deciduous shrub is favourite in our garden for the abundance of purplish-blue summer berries that follow the plant’s clusters of white flowers in spring. The flowers also attract pollinating insects which also provide a food source for birds in early spring. The berries are a favourite of a number of birds including those hard-to-attract warblers, orioles, colourful tanagers, catbirds, thrashers, mockingbirds and waxwings. Although the native species are always best to plant, Proven Winners Black Lace and Lemony Lace hybrids are outstanding editions to any garden and can easily substitute for Japanese maples.

Proven Winners describe their Black Lace elderberry as having “intense purple black foliage that is finely cut like lace, giving it an effect similar to that of Japanese maple. Pink flowers in early summer contrast with the dark leaves for a stunning effect and give way to black berries if a compatible pollinator is planted nearby.”

It’s their Lemony Lace version that I enjoy the most in our garden. The same finely cut foliage is here but in a golden or chartreuse colour to lighten up your landscape. The large clusters of white flowers in early spring before the foliage emerges are followed by berries. And they are deer resistant.

Juniper Juniperus Zones 3-9 Junipers are key sources of food and habitat for wintering birds. Their thick foliage provides ideal places for birds to escape cold winds and offer both nesting habitat and fruit for many birds. They can be grown as a shrub or tree and attract everything from warblers, grosbeaks, jays, sapsuckers, woodpeckers, waxwings bluebirds, robins, thrashers bobwhites and even wild turkeys.

Chokeberry Aronia Arbutfolia zones 4-9 Is a favourite of many birds. Its rather unimpressive spring blooms give way to bright red berries in summer and into fall when winter birds such as Cardinals and woodpeckers

Holly including Winterberry Ilex Verticillata zones 3-9 Holly is an ideal plant to attract birds with its colourful fruit ranging from red to yellow, orange to black and white. Of the more than 400 species that range from shrubs to large trees, hollies are primarily evergreen. Some, however, like winterberry, are deciduous. These are excellent sources of winter food for birds. The fruit ripens in the fall and can last all winter into early spring where they can provide a source of food for migrating birds or new arrivals. You can count on the red berries in the fall and winter to provide a natural food source for birds such as Bluebirds, woodpeckers, catbirds, thrashers and mockingbirds to name just a few.

Pagoda dogwood flowers in spring before giving way to an abundance of black fruit that the birds can't get enough of in the summer.

Best flowers to attract birds

It’s easy to see the direct relationship between birds and the many shrubs and small trees discussed above. The birds are obviously attracted to the fruit and sometimes the seeds of shrubs and trees. Indirectly, the insects that might be attracted to the fruits also serve as food for the birds foraging in our gardens.

That relationship is often not quite as obvious when it comes to the flowers we plant in our gardens. Aesthetics is usually the driving force behind planting a particular type of flower in our garden. Their attractiveness to pollinators and, perhaps, hummingbirds is sometimes the motivating factor behind planting flowers, but rarely do we give a lot of thought to the birds the flowers may attract. Here are a selection of flowers that will bring birds into your yard in search of the food they provide in one form or another. Let’s examine them in more detail.

Aster: The New England Aster, often seen growing on roadsides and in open fields in scrub land, is a good example of an important food source for birds in our backyard. This herbaceous perennial that can range anywhere between 3 feet to 6 feet in height puts out its colourful blooms in late summer into fall making it an important food source for migrating birds.

Its yellow centre surrounded in purple rays makes it a colourful addition to any garden at a time when most other flowers are disappearing. That’s the secret to the flowers’ importance for our native birds. This late bloom provides many insect species with vital autumn nectar creating an abundance of activity around the flowers, in turn providing an important food source for insectivorous birds right before or during migration.

Don’t be surprised to find an intensity of bird activity in your yard right at the time you think the birds are heading south. If that does not convince you to plant this hardy plant, consider that the seeds of New England Aster are also a food source for many birds including the White-Breasted Nuthatch (see earlier post here on attracting nuthatches), Black-Capped chickadees and American Goldfinches. Other backyard birds that may feed on Asters or the insects attracted to them are Blue Jays, Juncos, Indigo Buntings, Cardinals, Eastern Towhee, Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds and the Titmouse.

Black-Eyed Susans: Similar to the Aster, the Black-Eyed Susan is a late summer/fall bloomer that is a magnet for insects and, therefore, a good food source for insect-eating birds. Ranging from 2 to 3 feet in height, the Black-Eyed Susan and its many cultivars, also provide birds – especially American Goldfinches – with a source of food throughout the winter months. It’s important not to cut the stems of these plants down in fall. Leaving them standing provides both interest in the garden as snow builds up on them as well as an easily attainable food source for birds foraging in winter when there are fewer sources available to them. Many of the same birds that are attracted to Asters also depend on Black-Eyed Susans for a late fall and winter food source.

Coneflower: Falls into the same category as the Aster and Black-Eyed Susans when it comes to a food source for birds. The Purple Coneflower, with its prickly centre disk, is a favourite of many butterflies which, in turn are favoured by insect-eating birds. In addition to many of the birds mentioned above, Purple Coneflowers also attract Pine Siskins and Mourning Doves.

Columbine: Our native columbine is a woodland favourite that we know is especially attractive to hummingbirds. The red and yellow coloured flowers of our native columbine (see earlier post here) are rich with nectar and an obvious choice for lovers of hummingbirds. This same nectar also attracts a host of insects in early spring and so provides another food source for insect-eating birds from warblers to hummingbirds themselves. The seeds of the columbine may also attract various finches, including the Purple Finch.

Sunflowers: It’s no secret that the best flower you could plant in your garden as a food source for a host of birds is the mighty sunflower. Considering it’s the number one seed in our feeders, it only makes sense that we put it on our list of must-haves in our bird garden.

When one thinks of sunflowers, however, the first ones that come to mind are the massive Russian mammoths that can easily grow to 10 feet in height with their enormous flowers giving off an almost magical feel to our gardens.

These big boys are a great food source, make the perfect landing spots to photograph the birds, and a fun addition to the garden, but consider planting the native perennial varieties of Sunflower as well.

The native perennial Sunflowers, often referred to as the Woodland Sunflower, is much smaller, attracts bees and other insects, including many butterfly species including Checkerspot and Painted Ladies. It grows to between 2.5- and 6-feet tall with a central stem that becomes branched where the flowerheads occur. The blooms can last up to two months in mid-summer into early fall.

These long-rhizomatous plants often grow in large colonies in the wild where they grow in full or partial sun. It can spread aggressively if left unchecked and seems to be happy in most soils including loamy, sandy or rocky areas. It is pollinated by a host of native bees and is host plant to a number caterpillars to native butterflies making it an important source of food for insect-eating birds. Plant it along your woodland edges in full sun alongside Black-Eyed Susans and Bee-Balms for a stunning display and an insect/bird magnet.

The list of birds attracted to sunflowers is too long to list but includes Downy Woodpeckers, Indigo Buntings, Pine siskins, Purple Finches and Rose-Breasted Grosbeaks.

Don’t forget vines

Vines can be an important addition to a woodland wildlife garden providing nesting habitat as well as a food source for birds in the form of berries and the insects that are often attracted to these berries. One of the most important native vines for birds is Virginia Creeper.

Virginia Creeper: If you do nothing in your garden, there is a good chance that you will eventually have some Virginia Creeper in your garden. We have it in several spots in our woodland garden either growing along the ground or creeping up large trees. There is a reason why Virginia Creeper is so prevalent – birds love its fruit and are quick to spread the seeds either in the wild or in our gardens. That’s a good sign and one that this is an important native plant to attract birds to our gardens.

This deciduous vine grows between 30 to 50 feet with a spread of between 5 to 10 feet. It blooms from May to August, but its magnet is the berries it produces in the fall. The berries are a favourite of a long list of birds but most notable are the American Robin, Brown Thrasher, Cape May Warbler, Cedar Waxwing, Eastern Bluebird, Hermit Thrush, Eastern Phoebe, Scarlet Tanager, Yelow-Rumped Warbler, Pine Warbler, Red-Bellied Woodpecker, to name just a few.

Perhaps where many of us fall short in our attempt to attract the more unusual birds to our backyard is that we rely to heavily on providing food sources for our feathered friends, whether that is through commercial bird feeders or by planting an extensive array of native trees, shrubs, vines and flowers.

While food is a key ingredient to success, it’s important not to forget that birds are looking for a number of factors before they decide to raise their young in a particular area or backyard. By meeting as many of these needs as possible, we will be able to attract a greater variety of birds including those that are not normally common in backyards. Most of these more uncommon birds are primarily the insect eaters.

The following are important steps that, in addition to commercial feeders and planting native flora, will drive these birds into our yards.

I will not go into great detail here but, instead, urge you to explore my other posts on these important topics.

Build a wood or brush pile to attract wildlife

Build a brush or woodpile: Creating a brush pile in a corner of your yard can be a real draw for backyard wildlife ranging from small mammals, reptiles, amphibians and, of course insects. This in turn attracts the attention of birds, including raptors such as hawks and owls, in search of mice and other rodents – think rats - that might want to take up residence in your garden. I have two separate brush piles in our garden.

One is similar to an open compost of garden debris – branches, dried ornamental grasses, some fall leaves, mixed with spend soil from last year’s containers and hanging baskets – that is now well over 6-feet high and at least 12 feet in diameter. It is home to snakes, mice, chipmunks and who knows what else. I have seen a Cooper’s hawk in one of the branches above the pile just waiting for its dinner.

The other is more a traditional, very open wood pile made up of branches trimmed from out mature trees. I see it as a perfect home for a fox, groundhog or even a skunk although I have not seen any of those animals use it in that way to date. I do know that the top of the wood pile is a favourite spot for our red squirrels to sit and watch over the garden for predators.

For more on creating a wood/brush pile for a wildlife garden go here.

Adding several water sources is key for birds

It’s not enough to add a single bird bath to your backyard and think you’ve met the needs of every bird that might want a drink or bathe in your backyard. Birds can be fussy when it comes to bird baths and water sources.

A natural pond is always the best way to bring in a variety of birds, especially if there are no other natural bodies of water in the area, but many of us don’t want to get involved in setting up and maintaining a natural pond.

Instead, try setting up a series of water sources in your garden combining various styles of bird baths from traditional ones, to on-ground water sources and hanging bird baths.

Remember, though, not all bird baths are created equal.

I have written a comprehensive article on the best bird baths for your backyard. You can read it here.

Some are deep and preferred by larger birds, others are shallow and need to be filled daily but provide safe wading for smaller birds. Other bird baths can include a solar-powered pump to provide moving water.

On-ground water sources are often preferred by birds. We have a concrete leaf that gets tucked into pea gravel and is used constantly by everything from chipping sparrows to chickadees, but is a favourite of our resident chipmunks.

A solar-powered bubbling rock at the head of a dry-river bed provides moving water that birds, squirrels and chipmunks like to use daily.

We have even had a large hawk use one of our three large waterbowls as a bird bath.

By providing a host of water sources, birds can choose the one that they feel most safe. Taking a bath or even taking a drink can be a dangerous time for birds if predators are about. Providing a safe perching area nearby will allow them to case the area before committing to the bird bath as well as provide them an escape hatch if that is necessary.

For my earlier post on providing water for birds in your backyard, go here.

By combining some or all of these suggestions over time, I’m confident a greater variety of birds will find your backyard woodland/wildlife garden and choose to make it their home. Others will use it as one of their many stops on their daily routine and still others will drop down during migration to spend time in an area that meets their needs and helps them restore the energy they need for safe passage on their migration route.

Godspeed little buddies.

Don’t forget vines

Vines can be an important addition to a woodland wildlife garden providing nesting habitat as well as a food source for birds in the form of berries and the insects that are often attracted to these berries. One of the most important native vines for birds is Virginia Creeper.

Virginia Creeper: If you do nothing in your garden, there is a good chance that you will eventually have some Virginia Creeper in your garden. We have it in several spots in our woodland garden either growing along the ground or creeping up large trees. There is a reason why Virginia Creeper is so prevalent – birds love its fruit and are quick to spread the seeds either in the wild or in our gardens. That’s a good sign and one that this is an important native plant to attract birds to our gardens.

This deciduous vine grows between 30 to 50 feet with a spread of between 5 to 10 feet. It blooms from May to August, but its magnet is the berries it produces in the fall. The berries are a favourite of a long list of birds but most notable are the American Robin, Brown Thrasher, Cape May Warbler, Cedar Waxwing, Eastern Bluebird, Hermit Thrush, Eastern Phoebe, Scarlet Tanager, Yelow-Rumped Warbler, Pine Warbler, Red-Bellied Woodpecker, to name just a few.

Perhaps where many of us fall short in our attempt to attract the more unusual birds to our backyard is that we rely to heavily on providing food sources for our feathered friends, whether that is through commercial bird feeders or by planting an extensive array of native trees, shrubs, vines and flowers.

While food is a key ingredient to success, it’s important not to forget that birds are looking for a number of factors before they decide to raise their young in a particular area or backyard. By meeting as many of these needs as possible, we will be able to attract a greater variety of birds including those that are not normally common in backyards. Most of these more uncommon birds are primarily the insect eaters.

The following are important steps that, in addition to commercial feeders and planting native flora, will drive these birds into our yards.

I will not go into great detail here but, instead, urge you to explore my other posts on these important topics.

Build a wood or brush pile to attract wildlife

Build a brush or woodpile: Creating a brush pile in a corner of your yard can be a real draw for backyard wildlife ranging from small mammals, reptiles, amphibians and, of course insects. This in turn attracts the attention of birds, including raptors such as hawks and owls, in search of mice and other rodents – think rats - that might want to take up residence in your garden. I have two separate brush piles in our garden.

One is similar to an open compost of garden debris – branches, dried ornamental grasses, some fall leaves, mixed with spend soil from last year’s containers and hanging baskets – that is now well over 6-feet high and at least 12 feet in diameter. It is home to snakes, mice, chipmunks and who knows what else. I have seen a Cooper’s hawk in one of the branches above the pile just waiting for its dinner.

The other is more a traditional, very open wood pile made up of branches trimmed from out mature trees. I see it as a perfect home for a fox, groundhog or even a skunk although I have not seen any of those animals use it in that way to date. I do know that the top of the wood pile is a favourite spot for our red squirrels to sit and watch over the garden for predators.

For more on creating a wood/brush pile for a wildlife garden go here.

Adding several water sources is key for birds

It’s not enough to add a single bird bath to your backyard and think you’ve met the needs of every bird that might want a drink or bathe in your backyard. Birds can be fussy when it comes to bird baths and water sources.

A natural pond is always the best way to bring in a variety of birds, especially if there are no other natural bodies of water in the area, but many of us don’t want to get involved in setting up and maintaining a natural pond.

Instead, try setting up a series of water sources in your garden combining various styles of bird baths from traditional ones, to on-ground water sources and hanging bird baths.

Remember, though, not all bird baths are created equal.

I have written a comprehensive article on the best bird baths for your backyard. You can read it here.

Some are deep and preferred by larger birds, others are shallow and need to be filled daily but provide safe wading for smaller birds. Other bird baths can include a solar-powered pump to provide moving water.

On-ground water sources are often preferred by birds. We have a concrete leaf that gets tucked into pea gravel and is used constantly by everything from chipping sparrows to chickadees, but is a favourite of our resident chipmunks.

A solar-powered bubbling rock at the head of a dry-river bed provides moving water that birds, squirrels and chipmunks like to use daily.

We have even had a large hawk use one of our three large waterbowls as a bird bath.

By providing a host of water sources, birds can choose the one that they feel most safe. Taking a bath or even taking a drink can be a dangerous time for birds if predators are about. Providing a safe perching area nearby will allow them to case the area before committing to the bird bath as well as provide them an escape hatch if that is necessary.

For my earlier post on providing water for birds in your backyard, go here.

By combining some or all of these suggestions over time, I’m confident a greater variety of birds will find your backyard woodland/wildlife garden and choose to make it their home. Others will use it as one of their many stops on their daily routine and still others will drop down during migration to spend time in an area that meets their needs and helps them restore the energy they need for safe passage on their migration route.

Godspeed little buddies.

As an affiliate marketer with Amazon or other marketing companies, I earn money from qualifying purchases.

What tree should I plant in my backyard?

What tree should I plant in my garden? A question heard often in on-line forums and nurseries everywhere. The simple answer: Plant an oak tree. Its everything you want in a tree – solid, stately and it feeds, protects and is home to more forest creatures than any other tree you could plant. There is room in every garden design for an oak, and if you think there isn’t think again. Here are four great oaks to consider.

Four oak trees for your woodland wildlife garden

“We just bought our first house and we want to plant a tree. What’s the best tree to plant?”

It’s a question seen over and over again on gardening forums and one asked at local nurseries on a daily basis.

On Facebook gardening forums, the question is often immediately followed by a host of suggestions from well-meaning gardeners and homeowners offering up ideas ranging from tiny weeping hybrids to non-native, highly invasive trees.

Rarely does the word Oak tree show up.

Let me go on record to say that the best tree you can plant in your backyard woodland wildlife garden is an Oak. There are plenty of reasons to plant one of the 400 species of oak, but nothing is as important as one simple fact: Oaks support the most insect biodiversity of any tree in the woodland.

I remember when we moved into our current home. One of the first things I did in spring was to do an inventory of trees on the property. I was very happy to see a nice young oak tree growing happily in the back of the yard. Today it is a more mature oak that works hard for the birds and wildlife on our property.

If you are interested in exploring the world of shade gardening further, you might like my recent post on The Natural Shade garden.

An oak leaf covered in hoar frost in late fall.

Oaks are good for birds and wildlife

In his book Bringing Nature Home, Douglas Tallamy explains that a 2003 study found that a “single white oak tree can provide food and shelter for as many as 22 species of tiny leaf-tying and leaf folding caterpillars.” And that is just a tiny fraction of the fauna that depend on a single oak tree. In fact, the mighty oak supports 534 species of fauna, more than any other tree we can plant in our gardens.

It is followed by the willows, cherries and plums, in importance to fauna. All good choices when it comes to deciding what tree to plant in your garden.

If the Oak’s importance to wildlife is not enough, consider that of the 400 species of Oak, North America boasts 90 different species with 75-80 in the United States and 10 in Canada.

For more on the importance of oak trees in our garden and natural landscapes take a few moments to check out my other posts on Oak trees:

Oaks are long-lived trees

Oh, and no need to worry that the tree will die on you and leave a massive hole in the landscape, Oak trees traditionally live for hundreds of years. There’s a good chance your children will be watching the tree enter middle age long after you’re gone.

In Ontario and northeastern United States, that white oak you plant will grow more than 35 metres (that’s more than 114 feet) tall, can live for several hundred years and produce thousands of acorns every year to feed deer, squirrels (including flying, red and gray), chipmunks, wild turkeys, crows, rabbits, bears, mice, opossums, blue jays, quail, raccoons and even wood ducks just to name a few.

As Tallamy points out: “The value of oaks for supporting both vertebrate and invertebrate wildlife cannot be overstated.”

He explains that oaks along with hickories, walnuts and American beech, have stepped up to the plate following the demise of the American chestnut in supplying nut forage for various forms of fauna.

“Every oak tree started out as a couple of nuts who stood their ground.”

In addition, oaks – both living and dead – provide nesting cavities for our backyard birds ranging from chickadees, wrens, woodpeckers, owls and even bluebirds.

The tree species real genius, however, is what we alluded to earlier, and that is the astounding number of insect herbivores that oaks support in the forest ecosystem.

“From this perspective, oaks are the quinessential wildlife plants: no other plant genus supports more species of Lepidoptera, thus providing more types of bird food, than the mighty oak,” Tallamy writes.

(If you are wondering what the heck a Lepidoptera is: They represent an order of about 180,000 species in 126 families and 46 superfamilies of insects that includes butterflies and moths. It is one of the most widespread and widely recognizable insect order in the world, and your average oak is full of them.)

12 Cool facts about Oak trees

1) Not all acorns are created equally. Acorns produced by white oaks germinate just days after they fall from the trees. Acorns produced by red oak species germinate the following spring. Keep this in mind if you are trying to grow your woodland from seeds. It is estimated that only 1 in 10,000 acorns become trees.

Acorn hats after squirrels feasted on the fruit of the oak.

2) An oak tree produces about 2,000 acorns every year. These acorns contain plenty of nutrition including large amounts of protein, carbs, fats, phosphorus, potassium, calcium and niacin.

3) The root system of a mature oak tree can total hundreds of miles and its taproot grows vertically for some distance before branching out. This helps to stabilize the massive trees from wind, rain and hurricanes. Although most oak tree roots lie only 18 inches under the soil, depending on conditions, they may spread to occupy a space four to seven times the width of the tree’s massive crown. A good thing to keep in mind if you are planning any major digs or trenching in the area of your favourite oak tree.

4) Walking sticks and katydids mature on oak foliage, so if you have never seen a walking stick, plant an oak.

5) Oak trees appeared about 65 million years ago. They have a long history with records reporting back to the late Cretaceous deposits in North America and East Asia. Their survival might be attributed, in part, to the fact acorns and oak leaves contain tannic acid which helps protect them from deadly fungi and destructive insects

6) Some oak trees are not considered old until they hit the ripe age of 700 years. In fact, they can keep going until they hit 1,000 when growth begins slowing down. On average, however, a typical oak tree lives to be about 200 years of age.

7) During their long lives, an oak tree can produce 10 million acorns.

8) The largest living oak is said to be located in Mandeville, Louisiana. Its also considered one of the oldest clocking in at an estimated 1,500 years old

9) There are more than a few famous oaks in history beginning with the Emancipation Oak on the campus of Hampton University in Virginia which is designated one of the 10 Great trees of the world. The sprawling oak is 98 feet in diameter. In the 1860s, Mary Smith Peake broke the law when she taught African American adults and children how to read under the oaks’ branches.

10) The oak is the national tree of the United States.

11) Oak trees may be known by many in Canada and the U.S. as deciduous trees but, in fact, they can also be evergreen in warmer climates with mild winters.

12) Red Oaks are tough trees and can grow in hardiness zones from 2a through to 8b.

The perfect tree?

Sounds perfect, right? Hold on, there’s even more.

In your lifetime, the tree you plant will actually grow into an outstanding specimen that will have a dramatic impact on your landscape design. It will help to form the upper canopy of your woodland garden and you won’t have to wait until your golden years before you begin appreciating its presence in your landscape.

Its sheer size will help to block out the annoying neighbours and the rustle of its leaves will help to drown out the noise of the neighbourhood.

Too big for your yard?

‘The oaks are a large tree,’ you say. ‘Too big for my typical suburban yard.’

I say go big or go home.

Oaks are not “fast-growing” trees, but because of their eventual size they grow at a good pace. I’m guessing a pin oak planted in your late 20s or early 40s won’t outgrow most yards in your lifetime or the home’s second owners, if ever.

They grow big and strong and their roots run deep enough to give them good stability as they age. All these traits mean that you will not have to wait 40 years for the tree in your backyard to make a real difference in your landscape.

There’s plenty of time to plant smaller, understory trees for your woodland.