How hard is it to design and create a woodland garden?

Building a Woodland garden can be a fun and rewarding experience. The key is letting go of what you may have perceived as the perfect garden and let nature do much of the work. Your focus should be in establishing layering the site with tall trees, understory trees, shrubs and ground covers. I hope this blog will help you achieve your dream.

Ideas and tips to bring backyard landscape ideas to life

It’s not easy being a woodland gardener.

I mean, how long can you sit and watch the chipmunks playing on the rocks or the birds feeding their young from the nearby birch branch. And those pesky hummingbirds buzzing around feeding from the cardinal flowers, not to mention the feeders hanging on the pole beside you.

Eventually you’ll need a break from not having to cut grass, deadhead the flowers and prune the shrubs to within an inch of their life.

So how hard is it to create a woodland garden? It’s important to know that a woodland garden design is most likely the easiest of all gardens to maintain providing you’re willing to relax a little. It’s the ultimate low-maintenance backyard landscape, but it will require some work to get it established at the front end. Plant trees, shrubs and get a ground cover established and then relax and learn to work with nature rather than against it.

It’s not all fun and games.

Add the burden of trying to satisfy our friendly chipmunk after she returns for what seems like her 100th visit to load up on peanuts.

Over in the corner of the garden, a doe rests in the tall ferns, while her two fawns romp around waiting for their day to begin.

Like I say, “this ain’t easy.”

And the noise! The birds, the bees, it’s all so overwhelming.

Nap time can’t come soon enough around here.

If this sounds good to you, it may be time to reconsider your backyard landscape design and use the information contained here on this website for backyard ideas and tips to create your low-maintenance landscape.

If you are looking for assistance, consider picking up The American Woodland Garden, by acclaimed author Rick Darke, Capturing the Spirit of the Deciduous Forest. It can be difficult to find, but is often available on the used market. Alibris, an U.S.-based used book seller, has copies of The American Woodland Garden for approximately $25 if readers are interested.

“So how hard is it to create a woodland garden? It’s important to know that a woodland garden design is most likely the easiest of all gardens to maintain providing you’re willing to relax a little. It’s the ultimate low-maintenance backyard landscape, but it will require some work to get it established at the front end. Plant trees, shrubs and get a ground cover established and then relax and learn to work with nature rather than against it. ”

If you are interested in exploring the world of shade gardening further, you might like my recent post on The Natural Shade garden.

Let the leaves fall to the ground and just leave them there over the winter.

The decaying leaves are important places for insects and pupae to overwinter. Their decomposition helps to build an earthy, humus-rich soil alive with micro-organisms.

Birds depend on the insects come spring to feed their nestlings. (Check out this post for the complete story on leaving your leaves where they fall.) (Check out this post on how to use fallen leaves to build your Woodland soil.)

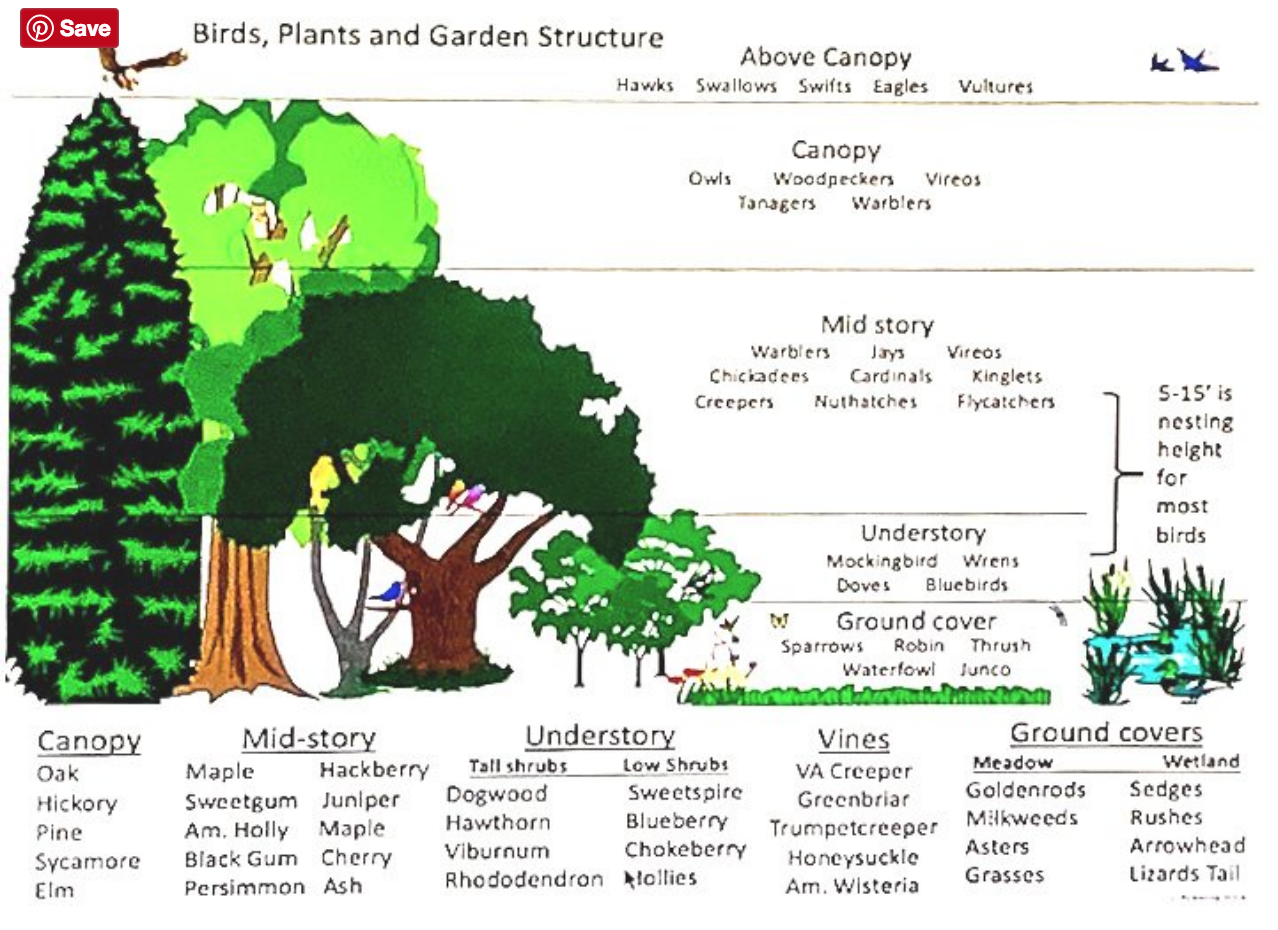

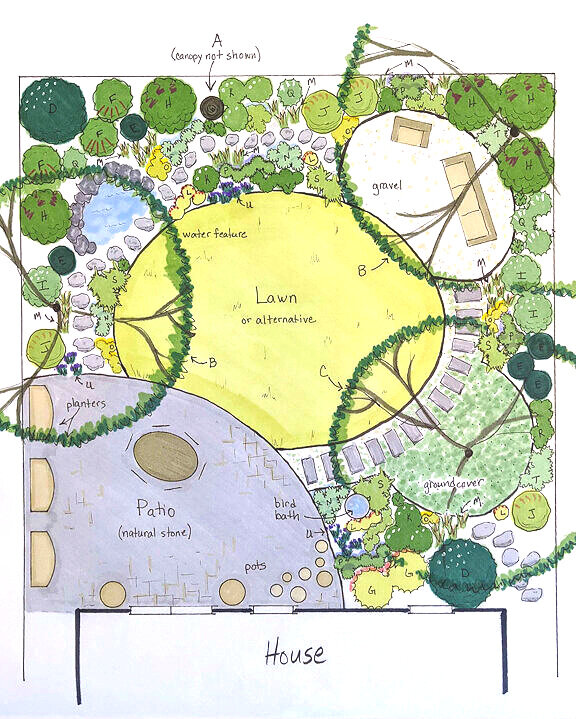

The ultimate woodland wildlife garden incorporates layering. This illustration shows what birds primarily use the various zones.

Relaxing is key to building a woodland garden design

To build a Woodland garden, it’s important to be willing to let nature do its thing and not worry about every little weed (let’s just call it a wild flower shall we).

Instead of spending our days weeding, let’s, instead, ensure our Woodlands are filled with a variety of ground covers that stop weeds from taking over the garden beds.

Try a little Snow-in-Summer in a hot dry area to cover the ground with a living mulch. Not only is Snow-in-Summer a beautiful ground cover, it offers outstanding opportunities for some beautiful selective-focus photography.

If you do it right, you’ll have plenty of time to photograph the daily life of your garden and its visitors.

Where living ground covers are inappropriate, let’s use organic mulch like shredded bark, pine needles or composted leaves to cover the soil and restrict any weeds that want to poke up through the soil.

Instead of pulling weeds all summer, let’s relax with a glass wine on the patio and enjoy our feathered friends. Let’s use that time to focus on planting more native plants to attract more insects to our yards that, in turn, will bring more birds to our woodland gardens.

And those hostas that were eaten by our family of deer, let’s just rejoice in the fact we are keeping the local wildlife happy and healthy. (Click here for a gallery of the wildlife that visit our Woodland garden.)

If you can live with that, welcome to my woodland garden blog. It’s aptly named Ferns & Feathers for its abundance of both ferns and feathered friends.

If you care to join me, we’ll tackle this thing together; learn from one another’s shared knowledge and experiences. We can take some time to enjoy a discussion or two about building the woodland garden one tree at a time through layering – from the forest floor to the tips of the tallest trees.

Along the way we’ll share our top 3… top 5… top 10. (Click here for my five favourite bird items or here for my top 5 woodland garden books.

We’ll share what products work best for us, (like this Gorilla Cart or a blue tooth speaker) some time-saving tips, work-saving tips.

I’ll also be sharing garden photography tips, tricks and ideas to bring out the best images hiding in your garden. Doesn’t matter if your best camera is an i-phone, a sweet little point-and-shoot enthusiast camera model or a full-featured digital 35mm camera. I use them all to document our garden and, with a little luck, can pass on some wisdom from a hobby I’ve been enjoying most of my life.

And I’ve got some time after recently retiring from almost 40 years in the newspaper business. So, with all this time on my hands, my wife told me to find something to fill it with or else… I decided to combine two of my great loves – gardening and photography – into a fun little spot on the web for like-minded gardeners to pull up an adirondack chair and join me and Holly (our four-legged friend) to share some tall tales, our victories, failures and a decent glass of wine.

Okay, let’s get this show on the road.

Best ground covers for a backyard woodland design

Ground covers are an integral part of a Woodland Garden. Ferns form the backbone of our garden both in the front and back yards, but there are many others. Here are three of my favourite ground covers that I use in my garden.

Three of the best ground covers for the shade garden

I once had a friend promise me some pink trilliums from her parents’ garden.

I knew back then that white trilliums turn pink as they pass their prime and begin going into decline.

You may ask, ‘what does this have to do with ground covers’?

Let’s just say promises of great things are not always what they appear to be, especially when it comes groundcovers.

So the promise of rare pink trillium plants was enticing, but not really what it appeared to be.

In the end, I took the pink trilliums knowing that next spring they would emerge as glorious white trilliums in our landscape eventually turning pink before disappearing again.

So what are the best ground covers?

The best ground covers are the ones that deliver what you need in a specific area of your garden.

Proper research will help guide you to the best plant to achieve the desired effect, rather than an-out-of-control planting that quickly takes over the entire garden.

Consider native plants whenever possible.

Ferns are ideal for shady places and sweet woodruff is always an ideal woodland addition.

Although not native, pachysandra can be an all-around proven winner in most gardens.

Gardeners know, however, that promises can be good or bad depending on how you perceive them. The very nature of a quick-spreading plant makes it a potential problem. Traditional groundcovers spread fast and are considered by many to have aggressive tendencies in our low-maintenance landscapes.

Making the right decision can be the difference in reducing the amount of work and adding to your burden in a big way.

Trying to pull out a huge mass of rapidly expanding, deep-rooted groundcover plants is no fun at all.

Looking for more information on ground covers? Please check out my other posts on ground covers I use in the woodland garden.

• Bunchberry ideal ground cover

• What is the easiest ground cover to grow?

• Creeping thyme as a ground cover

Backyard tips for using ground covers in your landscape

Word of warning, don’t make a mistake here and choose the wrong plant to use as your ground cover.

Many years back, I read a book about the value of using ground covers in your garden design. One of the most important lessons learned from it was to plant several different ground covers and let them compete with one another for supremacy.

It’s a lesson in landscape designs I have followed to this day. The results depend on several factors, including soil type and location.

In most cases, however, there is no clear winner. The ground covers live together in harmony battling for superiority and weaving a tapestry of texture and colour that gives variety to the garden and an informality that seems at home in the woodland or shade garden.

Here are three of my favourite ground covers for our woodland landscape design… there are more, lots more.

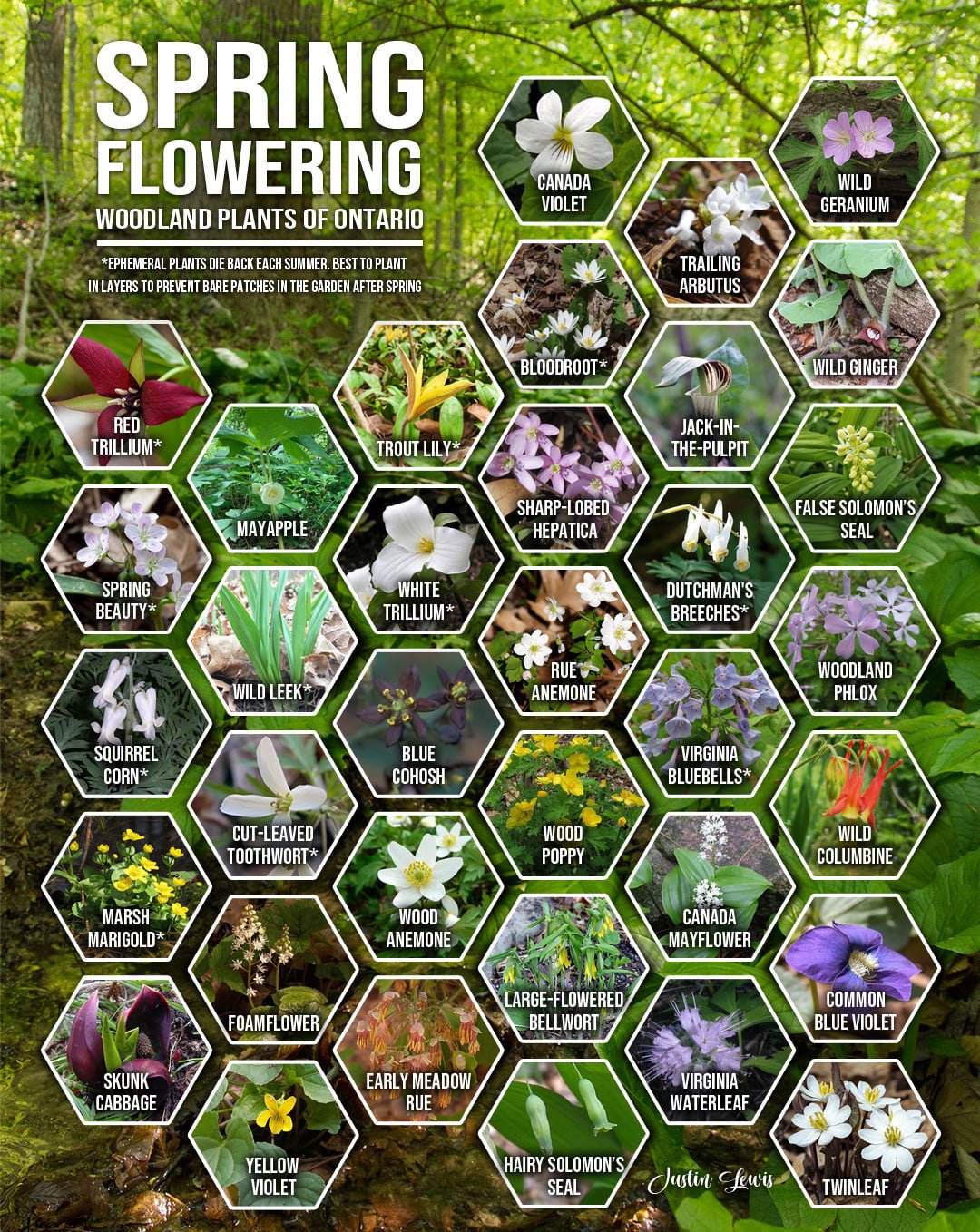

This highly informative poster created by Justin Lewis is best viewed on a tablet or desktop.

Ferns are perfect for the woodland garden

Coming in as number one in my garden because they are so darn perfect for a woodland garden is the humble fern. Although the massive, and some would say aggressive ostrich fern (link to proven winners website), dominates most of my gardens in both the front and the back, there are other ferns that make their home here too.

Want more information on creating a fern garden, check out my full post here.

Our ostrich ferns could not be more at home here. They dominate a large “wild” area in a corner of the garden once covered in a work-intensive lawn (link to earlier post about eliminating grass) that I am not sad to see go. Now, the ferns that can grow three-feet tall and spread out three to four feet wide, blanket the ground beneath in a lovely shade and provide perfect habitat for many of our wild critters.

In fact, It’s not uncommon to see a doe park her fawns on the edge of the ferns where they can hide in safety all day. A fox has been known to poke its head out from the thicket of ferns and reptiles, chipmunks and birds are often seen emerging from the fern glen.

In fall, the ferns turn a lovely shade of beige and become the landing zone for many of my leaves from the front garden. All winter, they serve as the ideal location for birds to root around for over wintering insects. I’ve seen wild turkeys working their way through the dead ferns snacking on a host of insects, seeds and berries.

In keeping with the woodland layering approach, understorey trees (my earlier post on building a woodlandand) shrubs grow up through the ferns. Several Redbuds (single and multi-trunk), a multi-trunk serviceberry, two azaleas and several dogwoods (both Cornus Florida and Kousa) as well as a variegated Curnus Mas are just a few of the understory trees that are at home among the ferns.

Other ferns in the garden include:

The Japanese-painted fern with its silvery fronds hi-lighted by red stalks is simply an outstanding performer in shaded areas where it can really put on a show. It’s not aggressive at all in my garden, but I can split them to add to their numbers if I want to have more and more. And believe me I do. Mine are in the front garden near a bird bath where they are happy in deep shade and are watered regularly when I top up the bird bath. These ferns perform best when they are kept moist.

The Ghost fern. I have only one located in our Japanese-inspired part of the garden, but it can be a show stopper. Larger than the painted fern but apparently a relative. Its soft, very light green colour gives it an almost luminescent appearance in shade, which is where it likely gets its name.

Maidenhair ferns are my absolute favourites. Their delicate fronds and black wirey stalks make these a must-have in any woodland. Although they can be difficult to grow, given the right conditions in a woodland garden, they will thrive. They are perfect in a Japanese-inspired garden. It’s important to note that they need plenty of shade and water. I have mine right up next to some granite boulders where their delicate fronds juxtapose with the heavy texture of the moss-covered rocks. They are also close to a birdbath that reminds me to keep them well-watered.

There are more we’ll get to but that’s a good start.

Any of the native groundcovers listed in the image above, are better than the following non-native groundcovers listed below. If you can use native groundcovers and they work in your area, always choose native over non-native.

In saying that, the following two groundcovers could work in your area as well.

Sweet Woodruff ideal for dry shade garden

The delicate, whorled foliage of Sweet Woodruff together with its early-spring white flowers make this a great ground cover for the woodland garden. It is not native and some would consider it aggressive, but it is not aggressive in my area and in the conditions where I grow it. I have mine under a Crimson Maple competing for space with trilliums, Ostrich ferns and hostas. It spreads nicely but I would not call it aggressive.

Pachysandra is strong performer any landscape design

So this one can be a little aggressive and certainly not a native to Canada and the United States. It’s best not to let it go unchecked by solid barriers.

It’s aggressive nature can be good or bad depending where you are putting it and how you want to use it. It’s pretty common, but it provides a 3- to 4-inch-high ground cover that can take some sun, has delicate white flowers in the spring and can cover ground fast and efficiently. Make sure you have a boundary so it and you know where its limits are. I use it in my front garden where it forms the main ground cover replacing grass that once covered our front lawn. Although many gardeners use it as a sole ground cover under evergreens or other large trees, I like to grow larger woodland plants up through the pachysandra, including hostas, native columbine, ferns, (including Japanese painted and maidenhair), Jack in the pulpits, solomon’s seal, epimedium, grasses and sedges.

Tips and ideas for simple DIY landscaping projects

Simple DIY landscape tips and ideas for for your back or front yard.

Landscaping tips to save time, money and your back

A garden isn’t created in a day, a week or even a month unless, of course, you hire a landscaping company to do it all for you.

Let’s face it, however, that can be an expensive path most of us would prefer not go down. And there is no real reason that most backyard landscaping projects can’t be tackled by homeowners themselves, maybe with some help from friends, family and even a few professionals.

The trick is to have a general plan (even if most of it is in your head) and to tackle the projects one at a time over a number of months and years.

In our front and back yards, my wife and I have completed most of the projects on our own. Those 8-hour days of heavy lifting and lugging six cubic yards of stone and mulch in wheelbarrows are thankfully behind us now, and we are generally left with maintenance and some minor landscaping projects.

The following are a few tips to help you tackle simple landscape projects on your own or with help from family, friends and even a few professionals to handle dangerous jobs or ones that would benefit from the use of heavy machinery.

• For more landscaping tips, check out my post on investing in landscaping or my earlier post on Ten Money Saving Landscaping Tips.

The garden pathway of pea gravel and stepping stones has withstood the test of time.

Building a pathway in the backyard

One of the first projects we tackled when we moved into our home more than 25 years ago was to build a simple pathway in the backyard that stretched almost entirely across the back of our home. Oddly enough, there was nothing connecting one back door to the other except grass – that same turf that covered almost the entirety of the 1/2 acre lot. (About 80 per cent of the grass has been removed. Check out my earlier post on the value of removing most of your grass.

See below, for more on how to remove grass the easy way.

Creating vignettes like this island of mondo grass in the dry river bed pathway adds interest to what could become a boring pathway of pea gravel and flagstone.

The pathway plan

The plan involved enlarging a too-small and -narrow garden that stretched across the back of the house between the two doorways leading to a back patio. By enlarging the garden by creating a larger half-circle garden it would not only give us more gardening space, but be one side of the arched pathway that would lead between the two doorways.

The original pathway needed to be wide enough to use with wheelbarrows and allow easy movement into the patio area of the backyard. By using a combination of pea gravel to form the base and square-cut flagstone to create stepping stones through the pea gravel, we were able to create an organic pathway that looked good, was permanent enough, but still left room to be easily changed over time.

There are a number of reasons I like this approach not the least of which is the satisfying crunch beneath your feet as you walk along the pathway (if you are on the pea gravel), and the almost instantaneous drainage that the pathway provides.

A deep culvert was filled in with river rock to create a dry river bed using pea gravel and different-sized river rock. Notice the grasses used to break up the river rock and give it a more naturalistic look.

The same design style was adopted in several spots throughout the property including in the front where a dry river bed was created to deal with a deep culvert that kept eating cars trying to turn around in the cul-de-sack.(see picture above) We also carried the same theme around the back patio where large boulders were placed surrounded by river rock and pea gravel, as well as the front Japanese-inspired garden. (see below.)

I also used the combination to tie in an existing pathway between the front Japanese-inspired garden with the pathway in the back. (See series of images below.) River rock outcrops and pea gravel fill a space between our property and our neighbours after we planted a strip of cedars to replace a tired hedge. For more on this project, check out this earlier post.

Getting to work building the pathway

In this instance, the grass was removed and two layers of black landscape mulch was put down to keep weeds grass or anything else from growing up through it. Normally, I would just put the black landscape fabric over the grass rather than remove it, but I needed the depth that removing the grass provided to get the proper depth of pea gravel. It’s important to lay the pea gravel to a depth of three to four inches, more would be even better. This completely stops any light from getting to the soil and further reduces the chance of anything growing up through the pathway.

The pathway of pea gravel and square cut flagstone is shown with its edges softened by wild geranium, hostas and snow-in-summer being allowed to freely grow over the pathway. the plants eventually need to be trimmed back but I like the look of a more natural pathway.

Two professional plastic edge strips (not the cheap flimsy stuff you can get at many “big box style” stores) were placed in a semi-circular fashion to hold back the soil of the garden and create a barrier for the pea gravel in the pathway.

Once the pea gravel was dumped and smoothed out, it was a simple matter to place the bluestone stepping stones in a way that was comfortable to walk on. It’s important to note that the flagstone stepping stones, though heavy enough to take typical foot traffic, do move about at times and need to be straightened from time to time.

Pathway building tips

Keep it simple. No need to complicate a simple pathway.

Pea gravel is an excellent choice because it can be easily topped up

Pea gravel and blue flagstone work nicely together creating a bluish-grey walkway through a garden. The combination is perfect for a hot, dry area or for a southwest or xeriscaping yard.

Use double layers of a high quality landscape fabric to ensure long-term success.

Use at least three inches of pea gravel (more is even better). Top up when needed.

Allow plants to grow over the edges to help soften the path. I have used hostas, Japanese painted ferns, black mondo grass and low-growing sedums to name just a few.

The result was a 4-5 foot-wide pathway that picked up from a path from the front of the home and guided visitors across the back of the home to the main patio while it passed through a rather formal garden on the left side and an enlarged, half circle style garden on the right.

Today, about 25 years later, the pathway continues to function much as it was originally intended to do.

Changes over time to the pathway

There have been minor modification to the original idea over the course of its life. One of the benefits of creating a non-permanent project is that it can evolve over time. In this case, the pathway was incorporated to form part of a dry river bed that actually crosses through the pathway.

The dry-river bed concept came about after I decided I wanted to create a birch grove that surrounded a pondless waterfall. (link to the making of our birch grove.) I loved the idea, but didn’t like the idea of a waterfall rising out of a flat area. A pondless waterfalls works best if it looks natural and, in this case, it would have looked like a man-made hill with a waterfalls rising out of nowhere.

I do have a hill, however, in the back of my property that just begs for a pondless waterfalls.

Instead of the pondless waterfalls, I went with a small bubbling rock that spilled out into a dry river bed surrounded by three clump birches (the equivalent of about 11 birch trees). The dry river bed runs down to the original pathway, across it and into the original garden which was covered in large river rock and pea gravel interspersed with small, compact hosta, an island of black mondo grass and a few Japanese Painted ferns.

The combined dry river bed, pathway and bubbling rock work together to create a large area across the back of the home.

Plants are allowed to spill over the edge of the pea gravel to create a more organic and free-flowing area without any hard edges. The black plastic edging on the one side has been removed and the other side has long disappeared under the plants that have been allowed to grow over it.

Another simple pathway idea

In another, less formal area of the garden, (see above) we used the same square cut flag stones as a stepping stones simply dropped into a thick bed of mulch. Again we used a visually pleasing curved path that leads from the side of the home, past our woodland fern garden to a grassy area in the middle of the woodland garden. The path begins at a deck box at the side of the home and leads past a firepit and a DIY moss garden nestled into an old copper firepit.

This simple pathway is as much aesthetic as it is useful helping to break up a large expanse of cedar mulch.

This series of images shows the making of a dry river bed around our Green Giant Cedars. Pictured here is the beginnings of the landscape project fallowed by images as the cedars being to fill out.

The cedars have filled in and are beginning to look natural. Notice the larger rock outcrops that help give it a more natural natural look.

A detailed image showing the variety of river rock that help to give a more natural look.

Massive boulders inspire Japanese-style plan

With the back landscaping under control, it was time to deal with a landscape issue in the front yard. The problem was that our home’s garage was converted into a family room years ago by previous owners, but the blacktop driveway ran right up to the front that is now the family room.

It never looked right to me but it took me several years to come up with an acceptable landscape plan.

It started when a neighbour offered me 11 massive boulders left over from a professional backyard landscaping project.

Those boulders became the inspiration for a Japanese-inspired front garden that created a natural barrier to the driveway flowing directly into our family room.

For more on this project, check out my earlier post here.

A portion of the Japanese-inspired garden in fall showing the large boulders, Japanese maple and Japanese forest grass

Japanese garden landscape tips

Keep it extremely simple in the Japanese tradition

Use at least one large rock or boulder (I used four in the garden)

Incorporate natural moss if possible

Try to incorporate some form of water (I used a square bird bath)

Use stepping stones to go through the garden

The Japanese-inspired garden plan

The plan was to use eight boulders down the side of the driveway to hold back the front garden, and then carry that theme across the front of the home by using three more boulders (always work in odd numbers) to ground the Japanese-inspired garden.

The boulders were carefully placed across the front of the driveway in a ratio of two to one. The concept was to create a canyon-like feel with two boulders on one side and another by itself on the other. A pathway – once again made of blue flagstone stepping stones set in analgesic??? screenings – ran through the middle of the canyon created by the placement of boulders.

Pea gravel and river rock created a dry-river feel but with a more formal look. Moss grows between the flagstones under a massive Japanese Maple on one side and a smaller, weeping Japanese maple helping to balance the single boulder on the other side.

To finish off the landscape plan, all the blacktop was removed from the front 3/4 of the driveway and replaced with red crushed gravel. The gravel was used for several reasons: First, its porous nature allowed rain water to more easily penetrate into the soil and feed the large maples whose roots ran under the driveway. Second; the red gravel offered a nice break from the predictable black top driveways and finally, it was a cheaper alternative that works in our semi-urban neighbourhood.

Be sure to check out my earlier post, for more on our Japanese-inspired front garden.

Removing turf the easy way

If there is one thing I dislike in a landscape, it’s grass. You can read all about my dislike of turfgrass here.

Even worse than having too much grass, however, is having to remove it before beginning a new landscape project.

The majority of projects at our home have not called for the removal of grass. Instead we have been lucky enough to be able to just kill it by either using newspapers and cardboard to smother it, or landscape fabric and mulch.

Quick tips to remove grass

use several layers of newspapers (preferably only B&W parts)

Cardboard is a good choice because it does not break down as readily as newspaper

Use a thick coating of mulch (shredded bark) to cover the newspaper or carboard. A think layer will just blow off exposing the newspaper and causing it to break down too quickly resulting in weeds etc.

After laying down a three- to four-inch layer of mulch, water it down regularly to weigh it down and ensure it does not blow away exposing the newspaper or cardboard.

If you need to remove large areas of grass, you can rent gas-powered machines to remove it, or manually operated sod removers, but if it’s possible simply cover the grass with newspaper and or cardboard and then heavily mulch it with shredded cedar mulch. This “sheet mulching” method simply starves the turf grass of light and kills it over the course of time (usually one full year.)

Once the grass is killed, you can begin your project, whether that is planting into the area or more major landscaping projects. By planning a year ahead, you can save yourself a lot of work, time and money.

Many gardeners frown on black landscape fabric as a means to kill grass. I’m not one of those people. Don’t use black plastic to kill turf, but I regularly use the breathable fabric covered by at least three inches of mulch. Once the grass is destroyed, you can pull up the fabric and begin planting. Or leave it down and cut large holes through it to begin planting.

Ideally, over time, all the fabric is removed, the soil can breath and wildlife has complete access to the entire garden.

Obviously using newspaper and or cardboard is a preferable approach but if you have huge areas to cover, you may not have enough to cover.

It’s a wrap: Landscape tips and ideas

Creating your perfect landscape should be fun and rewarding, not a pain and extremely expensive.

It’s important to realize that the landscape will likely never be fully completed and that it should be looked at as a marathon not a sprint. Tackle the most difficult and taxing projects while you are still young enough to handle the heavy lifting, but don’t be afraid to hire a professional if you think that the job is too much for you.

We hired a bobcat driver for one day to move the boulders into place along our driveway and place them in our Japanese-inspired garden. Before he arrived, however, I knew exactly where I wanted each and every boulder and guided him to the areas where the boulders were placed. With a few exceptions, the boulders fit perfectly into place and the job was done in just a few hours.

In a previous home, however, I moved similar sized boulders on my own using a series of levers. Needless to say, it was not only a lot of work but took forever to move the boulders just a few feet.

For another landscape project, I paid my nephew to build a small front patio out of flagstone and help me install front steps that looked like large natural stones.

In our most recent landscape project, we hired a student for several weeks to tackle some big projects that required little more than a big strong lad, a shovel and the willingness to get his hands dirty. The result was not only the completion of several smaller landscape projects, but feeling good about helping a young man during a summer of Covid when there were few jobs for University students. (See the full story here.)

Whether you do all the work yourself, use family friends, student help or a professional, you can save yourself time and money by developing a plan on paper or in your head depending on how you like to work, tackling one major project a summer and realizing that the goal is not to be done, but to create a landscape that pleases you, your family and the wildlife that will be by your side on this journey.

After all, it’s their home too.

Can woodland gardens be part of the solution to growing climate threats?

Are woodland gardens a solution to the world’s climate problems? If they are not the solution, they certainly can play an important role.

Until you dig a hole, you plant a tree, you water it and make it survive, you haven’t done a thing.

– Wangari Maathai

How trees cool our environment

This summer’s unbearable heat waves in most parts of the world are a stark reminder of the damage being done to our environment.

Temperatures are being smashed daily, weekly, even monthly. Parts of Spain were experiencing a heat wave that reached 45 C or 113 F in regions that were not used to dealing with this type of heat, threatening the lives of many, especially the elderly. Closer to home, Texas and other parts of the southwest are experienced unprecedented bouts of prolonged heat. Then there is flooding, forest fires and droughts.

Our world is telling us enough is enough. We need to start listening and taking action.

Are trees our only hope?

Here at home, if sitting under the shade of a tree is the only way we can be comfortable outside during these summer heat waves, it’s also a reminder of how important the thermal cooling properties of trees can be in our garden micro climates.

I am reminded of the saying, “Saving one dog will not change the world, but surely for that one dog, the world will change forever.”

It’s such a great saying that can also be applied to our gardens.

Planting one large shade tree in our garden will not change the world, but it certainly changes our world.

If everyone planted one large shade tree in their yard, think of how that might change the world.

However, one tree is not really enough. Think of what would happen if everyone planted ten trees on their properties and created a world of woodland gardens.

Now that would change the world for them, their families, their neighbourhoods, their cities… the world.

If you are thinking you could never plant ten trees in your small yard, think again. In a woodland, trees are planted in layers beginning with the tallest trees in the upper canopy, followed by smaller understory trees. You would be surprised how many trees can be fitted onto a typical suburban lot.

Creating a natural grove of trees in an area is the perfect way to add a mini-woodland forest of interdependent trees.

On our smallish pie-shaped front lot, we have a total of nine trees. This includes two large, mature shade trees (maples), three columnar birch trees planted in a small cluster, three Japanese maples and a native serviceberry tree. In the backyard, there are at least 20 trees that we either inherited with the property or planted ourselves. There are probably another 20-30 trees that have grown naturally across the back and on the edges of the property. These trees dominate our half-acre property and help to create the woodland environment.

Planting one large shade tree in our garden will not change the world, but it certainly changes our world.

This woodland approach is actually the thinking behind many environmental movements today, that I have wrote about on this garden website.

Irish landscaper and environmentalist, Mary Reynolds, and her books We Are the Ark and The Garden Awakening promote the creation of “natural arks” around the world to act as corridors for wildlife, while at the same time returning our backyards to natural areas. Gardeners can even hire Ms Reynolds to provide them with a landscape plan all their own. Click here for more information on hiring her for a personal landscaping plan.

There are movements to create Pocket Forests often referred to as Miyawaki method forests (link to my story) in urban areas to restore tiny natural woodlands in a fraction of the time it would normally take Mother Nature.

And there is the work of Professor Nadina Galle and her work with the Internet of Nature (link to my story about her work).Bborn in the Netherlands and raised in Canada Dr. Galle uses her background as an ecological engineer to tap into technology to create and protect the urban forest canopy on a much larger, city-wide scale.

But, you may ask, how can I as a gardener make a difference? Does planting trees really make a significant difference, and exactly how do trees help cool the earth?

How trees make a difference in our world

This latest prolonged heat wave should also be a wake-up call to the world about the importance of our natural forests and woodlands and the need to restore our tree canopy, not just in rural areas but – even more importantly – in our urban and suburban areas.

Cooling the environment around us is not the only benefit a tree creates. There are health benefits far beyond what we can imagine. Consider the popularity of Forest bathing as just one of the movements that is focusing on the health benefits of the woodlands.

Some quick by-the-number facts in case you need more convincing:

A single tree cools temperatures by providing shade and releasing water through photosynthesis which cools temperatures from between 2-4 degrees Fahrenheight.

An Arizona State University study found that an area of a block or two made up of parking lots and buildings with no tree cover or vegetation to speak of, can be cooled by about 8 degrees Fahrenheight or 4.4 degrees Celsius naturally with a tree canopy cover of at least a 1/4 of the space.

Trees, if planted around a home properly, can save 30 per cent on air conditioning bills.

A Nature Conservancy Nature report showed that planting trees can be a cost effective way to improve public health in two important ways: First, they reduce particulate matter in the air. This potentially dangerous particulate matter, that exacerbates asthma and other respiratory diseases, settles on the leaves of the tree where it remains until it is washed to the ground during a rainstorm. Second, trees cool temperatures by providing shade and releasing water through photosynthesis which cool temperatures between 2-4 degrees F . A single tree, however, can only cool an area of about a 100-foot radius around the tree.

Consider that the largest tree on the planet, nicknamed General Sherman, is 84 metres tall and has sequestered 1400 tons of atmospheric carbon during its estimated 2500 years on earth. To put that into perspective, today, it is estimated that humanity produces 1400 tons of carbon every minute.

There is always room for wildife in the woodland garden. This racoon was at home high up in a fallen tree.

In fact, in his book The Heartbeat of Trees, Peter Wohlleben gives an example of how a study conducted by Chicago University researchers found that a single tree planted on the lawn of an urban property can increase the benefits to the homeowner by the equivalent of an annual pay increase of $10,000.

The study, conducted with thousands of Toronto, Canada, residents, also showed that two trees planted in the front could provide the health and well-being benefits equal to an annual income increase of $20,000.

This study alone should convince homeowners of the importance of planting and maintaining trees in their front and back yards.

And, although a single tree can be effective in a limited way, several trees working together can make a profound difference in the environment where they are growing.

In his book, The Heartbeat of Trees, Wohleben writes: “A tree is not a forest. On its own, a tree cannot establish a consistent local climate. It is at the mercy of wind and weather. But together, many trees create an ecosystem that moderates extremes of heat and cold, stores a great deal of water, and generates a great deal of humidity. And, in this protected environment, trees can live to be very old. To get to this point, the community must remain intact no matter what. If every tree was looking out for only itself, then quite of few of them would never reach old age.”

Wohleben is not alone in promoting the benefits of multiple trees working together, like you would find in a proper woodland garden. Unlike a traditional garden, where there might be a single tree surrounded by a few shrubs and some flowers, the woodland garden taps into the power of multiple trees, along with the layering of shrubs, native plants and groundcovers to create a vibrant, living community that is able to create its own micro environment.

Fall is an outstanding time to enjoy the rich colours of the woodland garden.

The science behind how trees cool the environment

Now that we understand the importance of temperature control, let’s delve into how trees play a crucial role in cooling the environment.

Trees act as nature’s air conditioners by providing shade and reducing the overall temperature of their surroundings.

When sunlight hits the leaves of a tree, a process called transpiration occurs, where water is released from the leaves into the atmosphere. This evaporation process helps to cool the air around the tree.

Additionally, the shade provided by trees can significantly lower surface temperatures, making the surrounding area more comfortable.

By strategically planting trees in urban areas, we can create cooler micro climates, reducing the need for excessive air conditioning and mitigating the heat island effect.

So, next time you seek refuge under a tree on a hot summer day, remember that it’s not just the shade you’re enjoying, but also the natural cooling power of these incredible living organisms.

Now that we’ve explored how trees cool the environment, let’s dive into the fascinating science behind their cooling mechanisms.

It all starts with a process called transpiration, where water is released from the leaves into the atmosphere.

As sunlight hits the leaves, the stomata, tiny openings on the leaf surface, open up to allow water vapor to escape. This evaporation process not only cools the tree itself but also the surrounding air.

In fact, a single large tree can release hundreds of gallons of water into the atmosphere each day through transpiration. This moisture-rich air then helps to lower the temperature and increase humidity in its vicinity.

Additionally, trees also provide shade, which reduces the amount of direct sunlight reaching the ground and lowers surface temperatures.

The combination of transpiration and shading creates a natural cooling effect that can significantly improve the comfort of an area. Understanding the science behind tree cooling mechanisms allows us to appreciate the incredible role that trees play in regulating temperatures and creating more pleasant environments.

Real-life examples of trees’ cooling effects

It’s not hard to see the cooling effects of trees in real life.

In urban areas, where concrete and asphalt dominate, the heat island effect can cause temperatures to soar.

However, strategically planting trees in these areas can help combat this issue.

For instance, cities like Singapore have implemented extensive tree-planting programs to create green spaces and reduce urban heat. The result is a noticeable decrease in temperature, making these areas more comfortable for residents and visitors alike.

Another example is Central Park in New York City, which acts as a natural air conditioner for the surrounding area. The vast expanse of trees provides shade, lowers surface temperatures, and creates a refreshing microclimate within the park. This not only benefits the park-goers but also has a positive impact on the nearby buildings and streets.

These real-life examples are just a sampling of how trees’ powerful cooling effects can change our environment and work as nature’s air conditioners.

And yet, all over the world, governments choose to develop green space for financial profits. Where I live, for example, the Provinicial government, like many conservative governments around the world, has chosen to close its eyes to the benefits of greenspace and offer it to developers for the construction of expensive houses. These governments, despite the obvious warnings from experts, choose to not only ignore these threats, but deny that climate change even exists.

In doing so, they risk the lives and future of today’s citizens as well as the lives of future generations who will be forced to live in a world where catastrophic events are part of everyday life.

Besides doing our part to ensure these anti-environmentalists do not obtain or remain in political power, gardeners can take steps to ensure that the area around their home is doing its small part to protect the environment. Join Ms Reynolds’ ark movement, grow native plants and trees, protect wildlife and provide them with life’s necessities – water, food and shelter.

Alone we cannot change the world, but together, if we all plant a mini forest on our properties, we can make a real difference in our world, and the world around us.

Let’s start today by planting a single tree. Next year we can plant another, and another, and another.

Why you want moss in the woodland or shade garden

There should always be some mossy areas in the woodland garden, whether it’s growing on the ground or used in containers or even in a dedicated moss garden.

Use nature to inspire a mossy area in the garden

There are few features in a garden better than a soft cushion of beautiful moss.

Its pillowy look and tapestry of shades of green adds to its textural qualities and lends a quiet, almost soothing feel to a woodland/shade garden.

Finding an area in the garden where you can grow moss is an opportunity to create a quiet little woodland retreat that is likely to become one of your favourite spots in the garden.

The above image of moss-covered boulders is an area near my current neighbourhood that I discovered years ago, long before we even moved to our current home. We actually lived miles away in a different city when I discovered this mini-forest. I’ll never forget being there when a deer walked by me and through the forest. And, on another day, when I came across a deer asleep in a mossy area of the forest.

You can see why It has become a place of inspiration for me and the garden I am trying to create just a mile or two away.

It’s not a particularly large area, but it feels big because of the glorious moss that covers the boulders, the fallen trees and the soil. It’s part of the inspiration that we all need to create our gardens. Take a moment to read my post about Using nature as inspiration for our garden.

We are lucky to have moss growing in several areas throughout our woodland/shade garden filling in almost every crack between our flagstones and cement pavers, growing in shady areas of the grass, on our limestone boulders and in areas of the garden where I choose to encourage it.

If anything, I need to encourage more of it.

Moss is also featured in our DIY fire pit turned moss garden that I have wrote about in the past, and remains one of my favourite art elements in the garden.

The moss in the former firepit is growing primarily on a charcoal base from burned wood and is an excellent source of moss for other parts of the garden.

If I decide to add some moss elsewhere in the garden – to top off a container planting, in the Japanese-inspired garden or between pavers – it’s simple enough to peel off a little from the moss garden to get the moss started. If I need more, I can take it from other areas of the garden in small sections and encourage further growth. It all grows back quickly because it is happy where it grows.

It should comes as no surprise that moss is certainly one of my favourite features in the garden.

I know many “gardeners” do everything they can to keep moss out of their gardens and especially out of their grass. These gardeners are not only trying to fight Mother Nature, but missing out on the beauty of moss underfoot and its ability to create an aged patina that is difficult to obtain any other way.

In our garden, nothing would make me happier than to remove what little grass we have in our backyard and replace it with a large expanse of pillowy moss. Unfortunately, at least for now, most of our small grassy area is in a very sunny location and I doubt moss would grow well there.

Growing moss in a hot sunny area

In a hot, sunny area you are unlikely to have much success growing moss. In this case, use a moss alternative like Irish or Scotch moss (link to my earlier post) which are actually perennial plants that look like moss but do well in sunnier areas.

You should get away with an area that gets morning sun if you are willing to keep the moss moist by gently misting it on an almost daily basis. Also, be sure to keep it as free of debris as possible for best results.

It’s important to understand that moss can dry out and turn crispy brown and still be alive.

If you see moss that appears dried out, give it a good misting and it should bounce back. Also, if the moss dries up and begins to curl up, ensure that the moss is pressed down on the surface where it is growing, whether it’s on the ground, a concrete planter or between flagstones. Simply press it down firmly onto its growing surface until it catches and stays put on its own.

Water moss with misting or gentle rain setting

One of the modern hose nozzles that includes a misting setting is a great asset if you are growing moss. Try to refrain with hitting the moss with a strong stream of water from the hose.

The mist setting or the gentle rain setting are ideal ones to keep your moss looking its best.

Under the right conditions, moss is not difficult to grow.

How to grow moss in the garden

Mosses are not your normal garden plants. Their unusual classification as bryophytes can create problems for gardeners who want to treat moss like a normal garden plant.

Moss – and there are up to 25,000 different species – are non-vascular plants, meaning they lack most of traditional parts of a typical garden plant. Most importantly, moss lacks roots that traditionally give our plants stability along with a highway to move the nutrients they need to survive up into the plants, shrubs and trees.

Instead of roots, mosses have rhizoids, which are small hairlike structures. Their main function, much like roots, is to anchor the plant to a surface whether it’s soil, rock, tree bark, concrete….

Many mosses will suck nutrients up through the rhizoids and others draw in moisture and minerals from rain and the water around them through the moss’s highly absorbent surfaces.

Moss specializes in finding other ways to absorb water and nutrients. As a result the moss family are often found in shady, damp areas whether they are grow directly on the ground, on rocks, garden furniture or cement structures.

If you want to grow moss on the ground on top of the soil, it’s best to have slightly acidic soil that is fairly compacted with good drainage.

We are blessed with a sandy soil that seems perfectly suited to growing moss, but it also grows readily on screenings that we use between our flagstones.

Growing moss in the garden

There are plenty of recipes on the internet – including on this site here – on how to create moss on, for example, statuary and clay or cement planters.

By combining some existing moss in a slew with buttermilk and maybe some beer, and then painting this brew on to your statuary or planters, placing them in a shaded damp area and gently misting them regularly, you should be able to grow some moss on the garden elements.

It doesn’t always work as planned but, with a little experimentation, you should be able to grow your own glorious moss and begin to create a special place in your garden.

The making of a meadow

Landscape designer Angela den Hoed shares how she creating an impressive meadow garden in the side yard of her Pennsylvania home to be used a show garden for her landscape design clients. The result is a stunning garden that will slowly evolve each year to become a beautiful meadow garden teeming with insects, bees and other wildlife.

Landscape designer shares how she made her meadow garden

Removing sod and replacing it with a meadow is slowly taking root with progressive gardeners looking for a more natural approach to their landscape.

These gardeners are building meadows in the front, back and side yards to welcome wildlife that has had to make due with small islands of native and non-native plants and flowers for so many years.

Landscaper Angela den Hoed is one of these gardeners who have recognized the importance of meadow and prairie gardens and have taken the challenge of converting a large swath of turf in the front/side of her Carlisle, Pennsylvania home into a meadow.

It was a project that certainly came with its challenges. She chose to go with the most labour-intensive approach and, although the results after the first year appears incredibly successful, she admits it was a real learning process.

It just so happens, that was actually one of the key points of the entire project.

• If you are looking for ideas on using low-growing ornamental grasses, be sure to check out my post on Five low-growing ornamental grasses for the garden.

• More on Angela’s move from Engineering to Landscape designer here.

• More on Angela’s Woodland Garden design here.

Angela explains that installing the meadow was an important learning opportunity which she hopes to be able to take advantage of in future work with her landscaping clients, many of whom are beginning to ask about removing some or all of their grass in areas of their landscape to create a meadow garden.

In their book, Garden Revolution, How our Landscapes can be a source of Environmental Change, Larry Weaner and Thomas Christopher, write: “Native meadow is likely the best answer to North America’s over reliance on lawn, a means of saving the enormous quantities of water, fertilizer, herbicides, pesticides, and fossil fuels annually invested in the cultivation of turf. Unlike shrublands and forests, meadows can be established from seed in a relatively short time to gravitate toward open space and expansive views, attributes not common in a forest or shrubland.”

The authors ask why, then, does grass continue to dominate our landscapes?

They point to the quality of seed that has been sold in the past to create these meadows and the desire by homeowners to have an instant meadow in a single season.

For more on meadow gardening, check out my post: Fields of Gold: Sunflowers and Goldfinches.

“Meadows can work, but only if the gardener selects plants and uses techniques that reflect the local habitats and ecological processes that will affect their survival and proliferation. This is why successful meadow will look quite different in different regions.”

Their approach to creating a successful meadow is a fascinating look at working with nature using native plants and a more ecological approach. Although it is aimed at creating and maintaining large meadows with the least amount of work, their approach is certainly one that works in a mini meadow-inspired garden.

If you have visions for a larger meadow, Garden Revolution is a must read gardening guide to creating meadows and other inspirational gardens by working with native plants.

If you are interested in exploring this approach in greater detail, check out my more extensive post on Garden Revolution here.

Back to Angela’s experience installing her meadow garden. I could try to explain the process in my own words, but I think it’s best to allow Angela to tell her story in her own words.

The following is a series of questions and answers for Angela about her experience.

1) What are your short- and long-term goals with the creation of your meadow garden?

My immediate goal with the meadow project is to gain experience in meadow making that I can share with my clients and followers. My clients are starting to ask for seeded meadows, and I felt the best way to really understand it was to do it myself on my own property, using materials available to regular homeowners rather than landscape companies. Long-term I want the meadow to be an example for my clients, neighbours, and the general public to see what is possible in a typical residential site. I hope it shows the ecological and economic advantages of a native planting vs. mowed lawn.

2) I have been following your progress on Instagram an it showed that the creation of the meadow seemed like a lot of work. Would you recommend it for the average do-it-yourselfer or do you think it is better left to professionals like yourself?

The average do-it-yourselfer is totally capable of planting a seeded meadow on this scale. Once you get to maybe 1/2 acre or more, it may be better to hire a trained landscape crew. We did go with the most labour-intensive method of site prep, which I would definitely NOT recommend.

Our options for sod removal were to solarize, use herbicide, or cut it out with a sod cutter. We missed our window of sunny summer months for solarization and didn’t want to spray glyphosate on 1000 ft² of lawn. So, the sod cutter was an experiment. Rolling up and hauling away the sod was the labor-intensive part, and we still ended up needing to spot spray with glyphosate anyway.

The other site prep methods take a lot less hands-on time.

Is there a lot of maintenance in a new meadow garden?

3) How about up-keep since you put it in. Has it taken up a lot of your time keeping weeds etc under control?

With the sod cutter, I was hoping to not only cut out the grass, but any weed seeds as well. Unfortunately, here in the Mid-Atlantic we have centuries of weed seed deposits in the soil (the seed bank) and they can remain viable for a very long time. I was shocked at how many weeds came up, both before and after we seeded the meadow plants.

Afterall, this area had been lawn grass for 25 years. Weeds are generally a problem if they interfere with the meadow plants germinating (blocking their light) so I wanted a clean slate for seeding. I used the scuffle hoe at first, but eventually I resorted to glyphosate.

After planting, more weeds germinated. Most of these were benign albeit surprising (petunias?). Once the meadow plants germinate, they can generally outcompete the weeds, but a few more thuggish ones needed to be removed like mugwort, thistle, morning glory, mulberry trees, even a butterfly bush.

The biggest problem is the yellow nutsedge, which I will need to stay on top of for a few years. Weeding actually doesn’t take much time at all. I'm out there all the time checking out what’s going on, but only go after the weeds maybe twice a month. Most of them would not have had the chance to germinate if we had used a different site prep method. I anticipate a lot less problematic weeds in year two.

4) Where did you get your inspiration to create the meadow?

I’m not sure there was just one point of inspiration to create the meadow. It was probably a combination of naturalistic design books and classes that I’ve taken – I’m inspired by the work of Claudia West, Benjamin Vogt, Kelly Norris, Roy Diblik, Adam Woodruff, Noel Kingsbury, James Hitchmough, and others.

Naturalistic design and science-based ecologically beneficial plantings are where my heart is but are a pretty foreign concept for most homeowners. It’s a hard sell to clients when there’s no local example to refer them to. My garden has always been my experimental space, and now it's becoming demonstration space as well. A seeded meadow is at the far end of the “wildness” scale in terms of garden design. I hope to do a more intentionally designed plug-planted perennial “meadow” garden in the future, which I think bridges the gap between a seeded meadow and a traditionally planted garden with larger groupings of plants.

5) What are your plans for the meadow this year. Any additions, plant removals?

This will be year two for the meadow. In the first year the most visible plants were the nurse crop of oats and the mass of Rudbeckia. These will be significantly less prominent as more perennials and grasses start to take hold and bloom.

The first thing we will do this year is the cutback in late March, along with spot-spraying the clumps of lawn grass that came back up in year one. The front street-facing edge of the meadow was planted with potted plants in a more traditional garden arrangement to indicate intentionality. This part of the garden may get rearranged a bit this year, I am still holding space for a bit of artwork to be added there as well.

How long before wildlife show up in a meadow garden?

6) What wildlife did you see in the meadow this year?

I think it takes a while for the wildlife to find your new native plants. At least in the rest of my property that seems to be the case. However, there was a small flock of birds that were always hanging out at the bottom of the hill during the summer; they would all fly out when I walked by. There were plenty of bees, and a handful of monarch caterpillars on the milkweed. We also saw a hawk sitting on the roof looking over the meadow, he must think it’s a good place to hunt. I imagine a lot of the neighborhood rabbits will be moving in this spring.

7) What has been the reaction of neighbours on the street about the meadow.

The reaction has been positive. I’m sure they all thought we were crazy when we removed the sod last fall and it looked like a giant swath of bare soil until the seeds germinated in May. One neighbour said she wished she was brave enough to do the same thing. I have noticed a lot more walkers on our street since plants started blooming.

8) Is there anything you would have done differently if you could design and install it again. Tips for people thinking about creating one of their own.

I would definitely have used solarization as my site prep method. This requires more planning and patience. Basically, you must scalp the grass and then cover with black or clear plastic starting in June when the weather heats up, then leave it in place until just before you seed. This kills both the grass and the seeds in the very top layer of soil, and you can seed in the fall, winter, or spring. Giant sheets of plastic are not super neighbour-friendly though, so if doing this in a very visible area, glyphosate may be a better option. It also depends on the size of the meadow, as sheets of plastic will end up in the landfill. It’s a balance of size and your priorities. A few applications of glyphosate in the months before planting will also do the job, but many are uncomfortable with that.

I also should have eliminated the nutsedge ahead of time. The nutlets live 8+ inches below the surface and can prevent other seeds from germinating.

It will be a while before I know if I’m happy with my seed selection. I decided to not complicate it too much with a totally custom seed mix. I started with a readily available mix from Ernst Seeds and had them modify it by upping the percentage of perennials and lowering that of grasses. That’s primarily to get a heavier floral display in the meadow and help the neighbours see it as more of a garden. I also put in some plugs of Echinacea pallida (pale purple coneflower) and Eryngium yuccifolium (rattlesnake master) in small groupings for a little added interest. Hopefully the rabbits didn’t eat all of them! I can always add in a few other species in the future.

Five favourite plants for the meadow garden

9) What agricultural zone are you growing it in and what are the top 5 plants in your meadow?

I am in USDA growing zone 6b, in the Ridge and Valley ecoregion.

I would say the top most recognizable plants in the meadow would be:

• Echinacea purpurea (purple coneflower)

• Rudbeckia hirta (Blackeyed Susan)

• Asclepias syriaca (common milkweed)

• Aster novae-angliae (New England Aster)

• Monarda fistula (wild bergamot).

Why is a meadow is so important to the ecosystem?

10) Why is creating a meadow so important for gardeners and lovers of the natural world?

A meadow is an alternative style of garden that more accurately mimics how plants grow in nature. There is a much higher plant density than you find in a traditional garden setting, and consequently opportunity for much higher diversity – both in the plant species and the wildlife it can serve.

Even a tiny micro-meadow can pack in a lot of diversity.

There are 23 different plants in my seed mix plus the two plants added as plugs. With a seed mix, you can plant any size of garden with that much diversity in it. You are also hedging your bets against plant failure – if one or two plants don’t thrive in your specific conditions, there are plenty of other species that will fill in the gaps.

The obvious benefits of planting natives include providing food and habitat for local wildlife and supporting the local food web (hawks included!).

Beyond these are the reductions in fertilizer, fossil fuels, and noise and air pollution generated by lawn maintenance. We also get the additions of better stormwater absorption, improved soil health, and much higher carbon sequestration. These are ecosystem services that have been stripped from the original landscape and need to be restored as best we are able.

A Natural Garden: Bringing nature back to the landscape

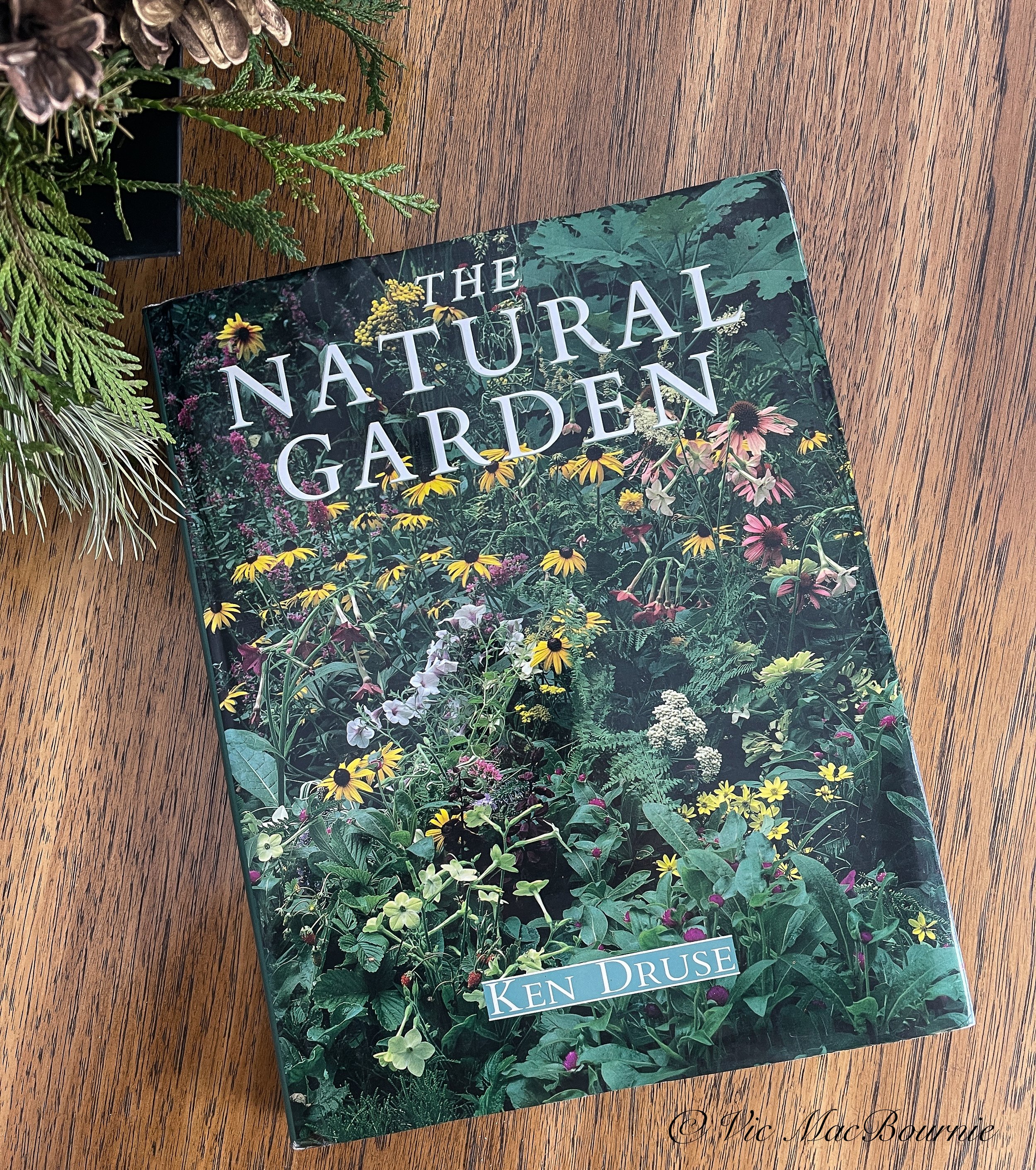

In 1989 Ken Druse wrote The Natural Garden. Was it a groundbreaking book that changed the way we garden today?

Is the Natural garden a growing trend?

Call it a woodland garden, a shade garden, maybe even a meadow garden – if it has a natural feel to it and is based on more native than imported and hybrid plants – chances are you are one of the many who are choosing the Natural Garden over the traditional garden style.

In his groundbreaking 1989 garden book, The Natural Garden, author Ken Druse introduces readers to what he calls the New American Landscape. Back in the 1980s, a natural garden certainly was not the norm.

Even today, most landscapes are typically dominated by large swaths of grass with tiny gardens hugging the foundation and maybe a lone tree trying its best to survive surrounded in a sea of grass.

More on eliminating grass in our landscapes in my earlier story.

Go to my earlier pot on the difficulties a lone tree in the landscape faces .

But A Natural Garden helped change the minds of enough North American gardeners that the concept of moving to a more natural stylized garden began to take shape. That concept is still struggling to take root in subdivisions all over the United States and Canada, but the onslaught of climate change, the decline of native plants and resulting birds and pollinators are forcing us to look at our garden practises in a new way.

I’ll never forget my first introduction to the book and the concept of natural gardening.

For more gardening books by Ken Druse, check out Amazon’s listings.

At the time I was putting together several Home and Garden supplements for the daily newspaper I worked at, and one of the owners of the local landscaping companies told me that his main source of inspiration was The Natural Landscape by Ken Druse.

I remember the cover was a combination of Black Eyed Susans and Purple Coneflower growing wild among Nicotiana and other plants. (see above)

It looked and felt natural. There was no single specimen plant sitting all by itself surrounded by dirt or mulch. There was no grass. The fact I loved Black Eyed Susans and Coneflowers sold me instantly.

Landscaper Koos, yes he was Dutch, was obviously ahead of his time. When he offered to take me around to some of the properties his landscaping company had worked on, I jumped at the opportunity.

This was before Instagram, Facebook and Twitter bombarded us with beautiful images of garden designs, and, to say I was blown away would be an understatement.

I will never forget going into the backyard of a new home with a typically-sized small backyard and being transformed to a northern landscape. Moss-covered, limestone rocks native to the area formed the structure of a waterfalls in one corner of the yard. It was backed by three beautiful 12-foot White Pine trees and formed the focal point of the suburban yard.

I couldn’t believe that a tiny backyard in the middle of a new subdivision could take on the look of being in a forest glade surrounded by native pine trees.

It wasn’t just the natural look that was inspirational, it was the combination of the sound of the moving water and the woodsy smells rising up from the earth and the pine trees. I was transported to northern Ontario’s Algonquin Park, where I spent time most summers immersed in nature.

That was an eye-awakening experience for me and one that I have never forgot on my journey to create our own woodland garden.

Although his book The Natural Garden played an instrumental role in shaping my concept of gardening, it wasn’t until recently – more than 30 years later – that I actually purchased the book. (It was not an inexpensive book in its day and although I do remember getting it out of the library at least once, I had never actually purchased it. That was before I discovered a mint copy on Alibris (used book seller) for only a few dollars – less than $4 to be exact. See image link below of The Natural Shade Garden for a similar price from Alibris. In addition, Alibris has The Natural Habitat Garden – a follow up book – used for a great price.)

I’m now a proud owner.

Is it as groundbreaking today as it was when it was first published?

There is no question that some of the plants suggested in the book would not sit well with native plant purists today, but the basic concept of the book is as fresh today as it was in 1989.

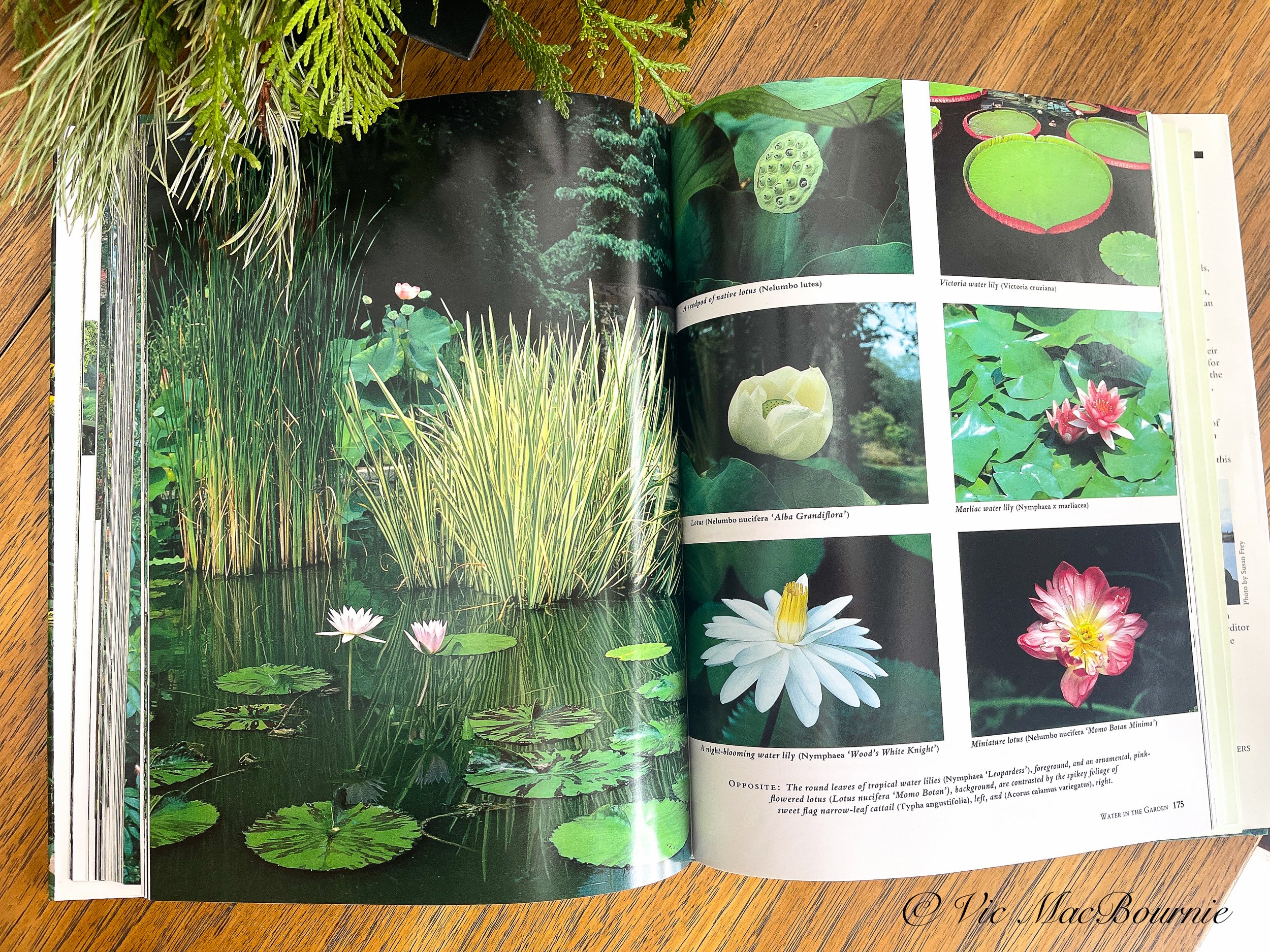

Let’s dig in a little deeper into this 296-page garden treasure.

The Natural Garden opens up by describing the author’s approach explaining that: “Essentially, the Natural Garden is a garden planted with species that are natural to their environments, species that would grow wild. Plants are chosen with an entire year, or years, in mind – they are not expected to work for just one season – and the garden design makes use of long-lasting natural materials. Thus the garden is beautiful year-round as well as being easy to maintain. Lawn is reduced to the minimum needed for recreation.”

A perfect description of what many of today’s natural/woodland gardeners are striving for in the their gardens today.

Druse writes about using nature as the primary source of inspiration while at the same time acknowledging that most of the true natural wilderness has almost disappeared.

“Think of wilderness simply as those places where plants grow unattended: California coastal highway meadows, Rocky Mountain glens of aspen, New England Woodlands, southwestern deserts, perhaps even the vacant lot at the end of your street.”

Druse goes on to say that the first step of any natural gardener should be to take a walk in nearby wild places and carefully noting what is growing naturally in the area. This inspiration should be the starting point in your pathway to your own natural garden.

Check out my earlier post on using natural areas as inspiration.

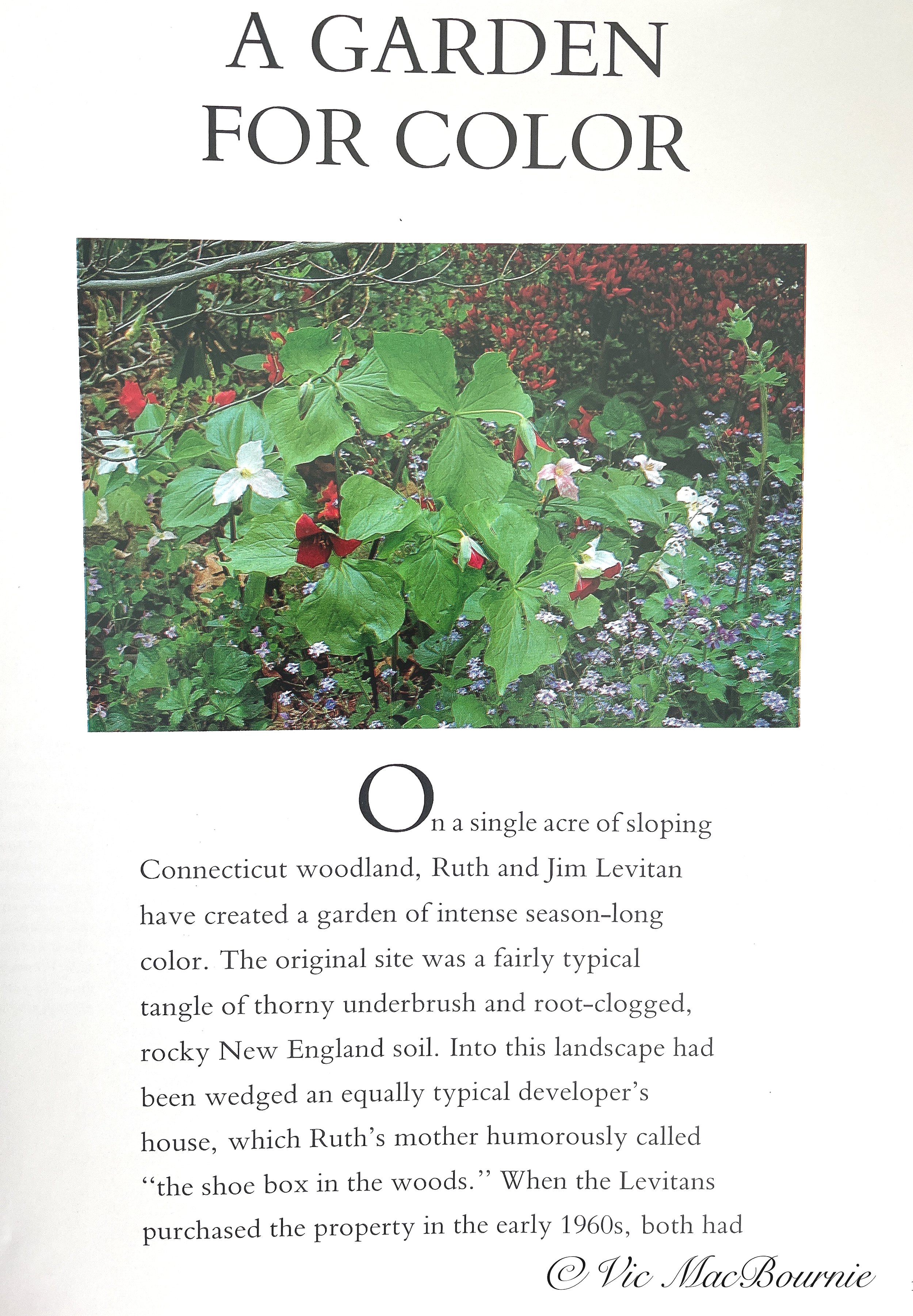

In his book, Druse offers a portfolio of natural gardens starting with an outstanding example of a New England woodland garden highlighted by Flowering dogwoods (Cornus florida) forming the understory with trilliums, Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema atrorubens), Forget-me-nots (Myosotis alpestris) combining in an impressive riot of colour that manages to combine the beauty of a woodland garden with a hint of an English border garden in the sunnier areas.

It’s not just vast woodland gardens that can get a taste of a more natural style of gardening. The Natural Garden explores a small garden in a big city providing tips on how to fill the space in a small garden with native plants, grasses and vines to maximize the space.

A seaside garden making use of ornamental grasses, a more natural English cottage garden and a California cliffside garden give readers a taste of how varied a natural-style garden can be and introduces them to the elements of garden design.

Five design elements for the natural garden

The Natural Garden focuses on how plants form the foundation of the design rather than paving, steps and walls made of hard-surface materials often associated with today’s traditional gardens.

1) Ground covers as the foundational design element. While lawns can’t be ignored. The Natural Garden prefers to focus on lawn aternatives that still rely on living ground covers. Native plants such as wild ginger, native mosses, ferns and even something like low-growing blueberry bushes can work in the right stiuations.

So too will wooly thyme, astilbe, and epimediums, just to name a few that have found their way into my garden. Druse also suggests a couple of plants that have long been used as ground covers but are not recommended today because of their invasive tendancies in certain growing zones, periwinkle (Vinca minor).

It’s important to do some research into plants – especially aggressive ground covers – before planting them.

For more on groundcovers in the woodland gardens, check out my posts here: Three great groundcovers for the woodland garden; Snow: Perfect groundcover for hot sunny areas; Three mosses for woodland groundcovers

2) Bulbs as early spring design elements: Bulbs are our spring time stars in the garden starting with snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis), Daffodils and tulips, but other bulbs can be used that put on their shows later in the season right through to fall. It’s important, however, not to plants them in straight rows. It’s much better to naturalize them in the garden beds or even in your grass and in with other groundcovers, letting them rise up in clumps in random areas of the garden.

Only bulbs that have the ability to spread and multiply can be naturalized; therefore, hybrid tulips do not work well. “Naturalized planting of bulbs, once established, are nearly maintenance free,” writes Druse.

A few to consider include: spring crocuses, dog-tooth violet (Erythronium dens-canis), grape hyacinths (Muscari) wood hyacinths ((Endymion hispanicus), Wind flower (Anemone blanda) and Ornamental onion (Allium giganteum). Lilies to consider include Canada lily (Lilium canadense) and Turk’s-cap lily (Lilium tigrinum) and tiger lily (Lilium tigrinum).

3) Perennials: While The Natural Garden does not focus entirely on natives, it’s a good idea to include only native plants when we are planting perennials in today’s gardens. That’s not to say we can’t enjoy what we have in our existing gardens providing they are not considered invasive. Plant that hybrid perennial if you want, but be sure to include the native species too to ensure insects and birds also find our gardens welcoming.

4) Ornamental grasses: Many modern gardeners might think ornamental grasses are a new trend in garden designs but The Natural Garden includes them as a key elements in the design process. For more on using ornamental grasses in the natural/woodland garden, be sure to check out my post here: Three ornamental grasses for the woodland garden

5) Vines in the garden design: Don’t overlook the value of vines to create texture and vertical cover in your garden, especially if it’s a small space. The Natural Garden describes vines as “something extra, a luxurious accessory” if you will. “While ground covers, or trees, or shrubs have practical uses, vines are more purely ornamental. Like necklaces, lace, icing, or gingerbread molding, they provide the perfect finishing touch,” Druse writes.

I’m not sure I agree with that conclusion, knowing that vines can provide needed habitat for birds as well as fall and winter fruit. Some like honeysuckles will attract hummingbirds, moths and butterflies as well as pollinators and other desirable insects and spiders.

But there is no question that they can add real beauty to a garden whether they are purely for looks or offer more to our wildlife. Once again, look for native vines to include in your landscape. Virginia Creeper is a great vine that has earned a spot in our garden and provides birds with berries in winter and late fall. Annual morning glories are also a staple in our garden,

The Natural Garden and why it’s more important than ever

As I wrote earlier, I am now the proud owner of Ken Druse’s book, The Natural Garden. I only wish I bought it back in the early ‘90s when the gardening bug first bit me. But, the beauty of gardening is that it’s never too late – never too late to plant the tree you always wanted, your favourite perennial or native wildflower.

Today, The Natural Garden is a little dated in some of its suggestions, but it’s also inspirational, especially in the middle of winter when the snow is falling outside and we need to dream about spring and the many projects we have planned.

Pull out the garden guides, the seed catalogues and our garden journals, but first get your hands on The Natural Garden and get inspired.

Heck, maybe for the price of a couple seed packets, you can find a mint copy of the book that changed my life and maybe yours too.

Exploring the art of flower photography

Flower photography is always rewarding, but it is especially so when you are photographing flowers in your own backyard that you planted and nurtured over the years.

An Iris photographed up close shows details that we may not normally notice. The image is more documentary and would need to be photographed with a tripod to maintain sharpness and detail.

Plant the seeds for creative flower photography in your garden

Flower photography offers us gardeners the perfect opportunity to combine our passion for flowers, with an outlet for creative expression.

Imagine the satisfaction of capturing a striking image of a flower that you actually started from seed in spring, or a drift of black-eyed-Susans that you planted two years earlier. The combinations of flowers we can plant in your garden opens up endless possibilities to create beautiful tapestries for selective focus experiments or simply colourful backgrounds for our favourite flowers

Besides, the thrill of creating beautiful images, the process of documenting your garden from year to year certainly has much value for off-season garden design planning.

This image of a tulip is an example of a more creative approach to flower photography. The soft background and delicate lines as well as the off-centre composition captures the viewers attention.