Cornus Kousa: Outstanding tree and why you need to reconsider planting it

The Cornus Kousa is a spectacular accent or understory tree for the woodland garden. Although it is a spectacular tree in full bloom, it is native to China.

Consider starting with the native Cornus Florida

Without a doubt the most impressive understory tree in our woodland garden is the Cornus Kousa, but I urge gardeners thinking about planting one to reconsider.

It’s not that the Cornus Kousa isn’t spectacular in flower – it is.

It’s not that the fruit that follows is not impressive and a favourite of our local squirrels and chipmunks because they are.

And, it’s not because these elegant, horizontally branched trees are susceptible to disease and deer predation, because they are almost totally free of disease and other garden pests.

Sounds like the perfect tree, right?

Just one big problem – and it’s a problem many of our most visually pleasing and impressive plants and trees have in common, – it’s not native to North America. Its home is in China and other parts of Asia where, I am sure, it is a favourite food source for their native insects, caterpillars, birds and mammals. In fact, you will often find the plant referred to as the Chinese Dogwood.

The difference is, their local fauna has grown up and adapted to Cornus Kousa and, as a result, are able to use it as a host plant, a food source and provider of habitat.

With all that said, I have two massive Cornus Kousa trees growing in my yard and absolutely treasure them for their mid-summer display of large, cream-coloured flowers that bloom for months during the summer followed by bright red eatable raspberry fruit that eventually get picked off by red squirrels, grey squirrels and chipmunks.

Be sure to read my detailed look at the Six best Dogwoods in my garden.

More of my posts on Dogwoods

For more information on Dogwoods, please check out my other posts listed here:

Dogwoods: Find the perfect one for your yard

Flowering Dogwood: Queen of the Woodland garden

Bunchberry: The ideal native ground cover

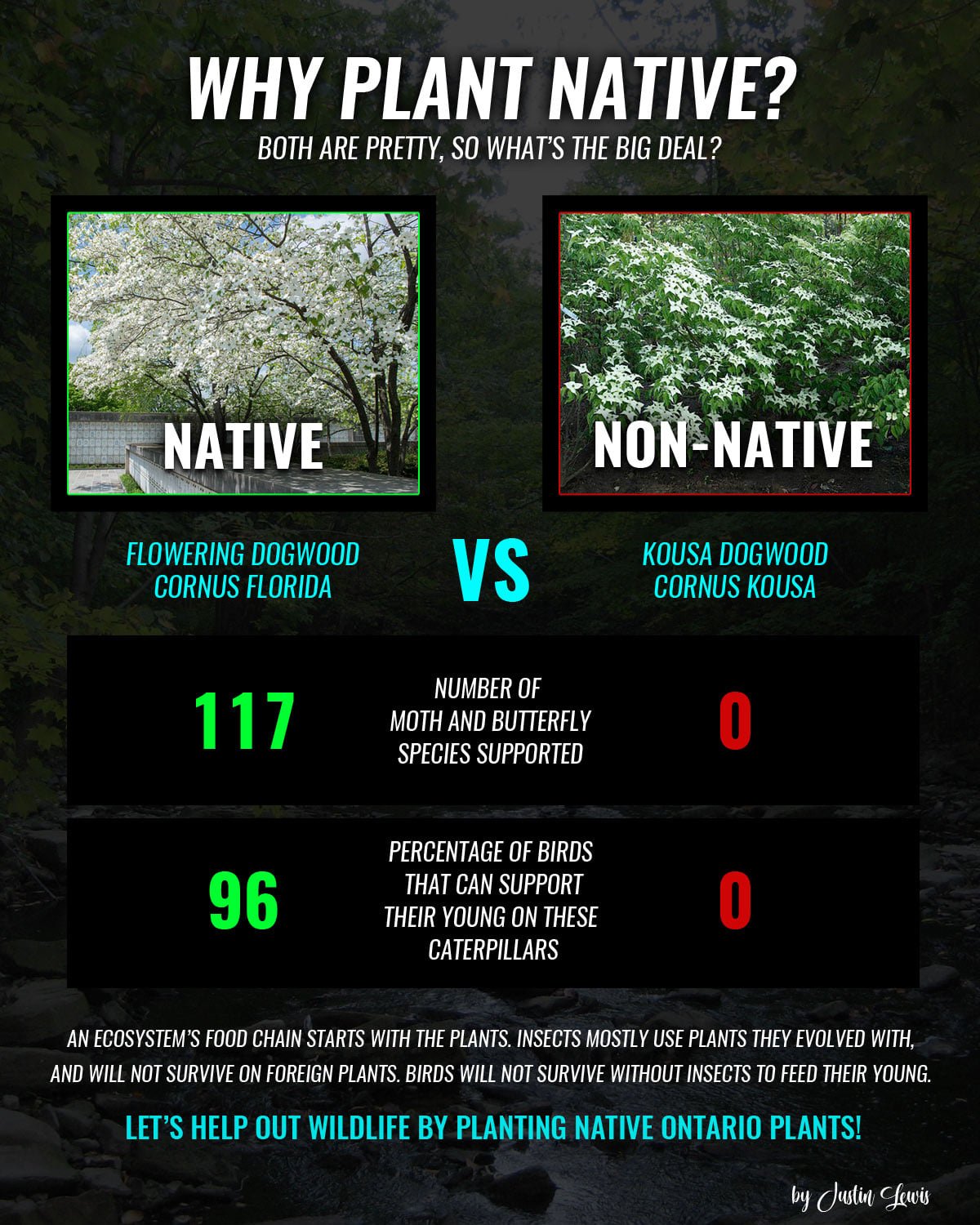

This graphic was produced by Justin Lewis and shows the benefits of planting a native dogwood over a non-native.

So, when I say “reconsider” planting one of these small, but impressive trees, what I really mean is before you plant one, make sure you’ve already planted the equally beautiful (some would say more beautiful) native Cornus Florida or Flowering Dogwood.

In fact, the combination of the Cornus Florida and Cornus Kousa growing alongside one another is an impressive site that creates an outstanding blooming period beginning in May with the native dogwood and continuing into late summer with the Kousa dogwood.

In our woodland garden there is also a couple of early blooming native Redbuds growing with the two dogwoods creating a a truly dramatic spring show. A multi-stemmed serviceberry is also beginning to make its presence known in the grouping that grows out of our massive fern garden. Be sure to check out the full story on our fern garden.

Our native Flowering Dogwood blooms about a month earlier than the Kousa and on mostly bare branches which make its bloom even more impressive than the Kousa dogwoods. It is also a host plant to a huge variety of insect larvae and caterpillars as well as a favourite haunt of native birds including the elusive bluebird and the cardinal, just to name two stalwarts.

Be sure to check out my full story on the Flowering Dogwood (cornus Florida).

An example of Cornus Kousa fruit (raspberry like) ripening on the tree.

But back to the Cornus Kousa. And why it is such an outstanding landscape plant either used as a specimen or as an understory tree in the woodland or shade garden.

Cornus Kousa has more of an upright habit, making it a little better suited to smaller or more narrow properties.

Close-up of ripening bright red fruit of the Cornus Kousa.

How to grow Cornus Kousa

The Cornus Kousa grows in zones 4 through 9 and likes a rich, well-drained acidic soil and adequate precipitation to look its best.

Chinese Dogwood is a multi-stemmed deciduous tree with an expected growth of between 25-40 feet (8-12 m) tall at maturity, with a spread of about 25 feet. If left natural, it has a low canopy with a typical clearance of about 3 feet from the ground. It grows at a medium rate, and under ideal growing conditions should live for 40 or more years.

Cornus Kousa’s best features

Cornus Kousa’s most prized feature is its horizontally-tiered branches along with its showy clusters of white flowers (actually bracts, the flowers are contained inside the four bracts) held upright atop the branches in late spring through summer depending on its location in the garden. The Cornus Kousa flowers are more pointed than the native Flowering dogwoods more rounded ones.

It has bluish-green deciduous foliage that turns an outstanding brick red in fall. It does best in full sun in cooler climates to partial shade and will not tolerate standing water. Cornus Kousa is also resistant to the dogwood anthracnose disease making it popular in areas that experience outbreaks of the fungus disease that can be fatal to the trees.

How to prune Cornus Kousa

This low-maintenance tree should be pruned sparingly after flowering to maintain its horizontal branching that looks at home in any Japanese-style garden as well as a traditional woodland. It’s also a good idea to mulch around the extensive root zone to protect the tree’s roots from drying out.

Hybrids offer best of both

The popularity of the Cornus trees have prompted Rutgers University to create a host of hybrids between Cornus Kousa and Cornus Florida, selected for their disease resistance and flower appearance.

Some of the popular cultivars include: Beni Fuji with deep red-pink bracts, Elizabeth Lustgarten and Lustgarden Weeping notable for its smaller size and weeping habit, Gold Star a slower growing tree with a broad gold band on its leaves and reddish stems, Satomi with deep pink bracts and leaves that turn purple to deep red in fall.

Flowering Dogwood: The queen of the Woodland garden

The flowering dogwood is an icon of the American landscape with its spectacular spring flowers followed by red berries that birds cannot get enough of as they ripen.

The Flowering Dogwood (Cornus Florida) combines everything a gardener could want in a backyard tree.

If you are lucky enough to live in a region where you can grow this iconic native American flowering tree, whether it’s in your front as a specimen tree or as an understory tree in the backyard woodland or shade garden, you should waste no time sourcing one or even several for your front and back gardens.

In our backyard woodland garden, we have several that fill the garden with showy spring flowers followed by berries in summer and outstanding fall colour.

Its native range is New England south to northern Florida, west to the Mississippi and even beyond. In Canada it finds its range in Southern Ontario’s Carolinian zone.

In the cooler growing zones found in Northeastern U.S. and parts of Canada in zones 5-6 for example, Dogwoods can take more sun than the hotter zones farther south where they are best grown in light to partial shade.

Travelling through the Great Smokey Mountains and along the Blue Ridge Parkway in early spring is perhaps the ideal way to experience magnificent Flowering Dogwood and Redbuds both in full bloom along their still-bare branches.

The Flowering Dogwood grows to about 30-35-feet tall in the wild (often smaller in gardens) with a spread that is about two-thirds or almost equal to its height. It’s a wide spreading mounding tree with branches that can droop right to the ground if left to grow naturally. It likes to grow in partial shade to full sun and prefers moist to dry woodsy loam to a clay-loam.

Flowering Dogwoods flowers from March, April and May followed by clusters of 3-5 red berries (or drupes) from August through October – that are highly favoured by birds and other mammals. It is the queen of the Carolinian forest and and is at home growing in zones 2 through 9. Its mottled bark creates winter interest to the already elegant, horizontal branching of our native tree.

Be sure to check out my extensive article on the Six Best Dogwoods for the Woodland Garden.

More of my posts on Dogwoods

For more information on Dogwoods, please check out my other posts listed here:

Dogwoods: Find the perfect one for your yard

Cornus Kousa: Impressive non-native for the woodland garden

Bunchberry: The ideal native ground cover

Pagoda Dogwood: Small native tree ideal for any garden

Cornus Mas: An elegant addition to the Woodland Garden

The tree’s branching habit of stretching right to the ground suggests that it wants to protect its roots from harsh sun and other root-zone incursions, so it’s a good idea to provide some protection around the tree’s root zone.

A heavy mulch around the root zone will help to hold moisture as well as protect it from direct sun and the damage lawnmowers create when working closely to the tree’s trunk. Do not pile the mulch up around the trunk of the tree. Leave a well stretching several inches to a foot or two around the tree to limit disease and insects.

Our native dogwoods do suffer from disease including Anthracnose, which can take root after a long rainy, cool spring. Anthracnose can attack the flowers and leaves of the tree all summer long and, can eventually kill the tree if it persists for several seasons.

If planted in a location, preferably as an edge-of-the-woods tree, where it gets morning sun to burn off the moisture and dew from the flowers and leaves, Anthracnose is unlikely to be a problem. Ideally, the tree should be planted where it can get afternoon shade to help it escape the extreme heat.

The Flowering Dogwood has dark red to purple fall colour. In spring it makes a great companion for Witchhazel, Redbud and serviceberries as well as the non-native asian relative the Cornus Kousa.

Cherokee Chief is a particularly nice cultivar with a pinkish flowers colour. Some cultivars are available with a darker red colour but the native still stands out best with its white to cream-coloured flowers.

What’s the difference between Cornus Florida and Cornus Kousa?

It’s important to note that the native Flowering Dogwood is not the same as the non-native Cornus Kousa, which is a popular dogwood sold at many local nurseries.

Although the two understory trees share many similarities – including large white flowers followed by red fruit – their differences are so widespread that they are really not interchangeable in the landscape.

Where they do stand out in the landscape is when you can combine them for early spring flowering in the native dogwood, through summer and late summer flowering by the non-native Cornus Kousa. The combination brings the woodland to life in an elegant display of gorgeous dogwood blooms that last almost throughout the gardening season.

• Where the native dogwood flowers in spring into early summer, the Cornus Kousa flowers pick up where the native ones begin to die out and offers flowers into late summer.

• Where native dogwood flowers grow more or less on bare branches that really show off the flowering bracts, Cornus Kousa flowers later in summer after the leaves fill out on the tree providing a beautiful showing but not quite as impressive as that offered by the native Flowering Dogood.

•Where native dogwood’s fruit is more like a drupe in clusters of 3-5, Cornus Kousa tends to put out singular fruits that look like raspberries.

• Where native dogwoods grow in a mounding, horizontal habit, Cornus Kousa tends to grow in a vase shape that eventually sends out horizontal branching if left untrimmed.

• Where the native dogwood is susceptible to disease and deer predation, Cornus Kousa, is more or less free of these problems including Anthracnose.

• Where the native dogwood is a magnet for local wildlife both as a host plant for larvae and insects through to providing an excellent food source for birds and other mammals, Cornus Kousa is neither a host plant for native caterpillars and insects, nor are its berries a great source of food for birds. Some birds and mammals (Squirrels and chipmunks) will eat the fruit but its certainly not their first choice.

• Cornus Florida supports up to 117 moths and butterflies, whereas Cornus Kousa is not known to support any in the larval stage.

• Cornus Florida also supports close to 100 birds from caterpillars that use the tree as a food source, while Cornus Kousa is not known to support any birds as a larval host.

How to water a Dogwood tree

Since the dogwood grows in a very horizontal fashion it has a very wide “drip zone.” And, because this drip zone extends out so far from the trunk of the tree, it serves little to no purpose watering the tree close to its trunk.

Look up to establish how far the tree’s branches stretch out from the main trunk and use that as your watering zone for the tree. Slow, deep waterings are necessary to keep the soil around the tree’s roots cool and moist. An all-day drip being moved around a mature tree throughout the day would be ideal during hot, dry periods with low rainfall.

Smaller, or newly planted trees would need less watering, but be sure to water deeply around the entire perimeter of the tree.

How to prune a flowering dogwood

The dogwood is a slow growing tree that tends to self prune over time. Deadwood can be cut out as it appears, but it’s important to maintain the tree’s elegant horizontal branching habit rather than try to shape it into something it does not want to be.

If grass is growing under the tree (never a great idea, better to have either living, or bark mulch), it’s best to limb up the tree as it grows and then maintain it by pruning the trees outer branches lightly to reduce the weight of the branches laden with flowers.

Try not to heavily prune the tree by taking out large branches because you will be removing the best attributes of the tree – primarily its spring flowers. It is best to just remove the smaller outer branches to reduce the weight and thus help to keep the skirt of the tree high enough to walk under.

I always prefer, if possible, to plant the tree in an area where it can take on its natural shape and not be severely pruned up.

If you are unsure how to get the most out of your dogwood, it’s probably best to hire a well-respected pruning expert to maintain the shape of these trees. Ensure the tree company is familiar with pruning ornamental trees and not just one that specializes in removing trees or large dying branches.

Cornelian Cherry: Elegant addition to woodland garden

Cornus Mas is the perfect replacement for the overly common Forsythia. It’s early spring yellow blooms flower at about the same time as Forsythia but the small tree offers much more architectural elegance in the landscape than the straggly-look of the Forsythia.

Consider replacing Forsythia with Cornus Mas or Spicebush for spring colour

It’s hard to imagine why homeowners choose to grow a Forsythia bush when a Cornelian-Cherry dogwood (Cornus Mas) is a much better choice in every way, shape and form.

In other words, when it comes to shape and form, Forsythias fall short in every way.

Imagine a small rounded tree with horizontal branches sporting elegant yellow bunches of flowers that eventually give way to bright red fruit or drupes. Now, compare that to a scraggly green bush that needs constant pruning, which is all homeowners are really left with after the forsythia blooms in early spring.

There is no competition.

While the over-used Forsythia has a straggly, vase shape that is not particularly pleasant after its brief early spring blooming period, for some reason it continues to dominate the suburban landscape over the inherent beauty of the Cornelian Cherry’s early-spring clusters of yellow flowers.

Right about the same time as the forsythias are blooming, the bare branches of the Cornelian Cherry (Cornus Mas) are covered with delicate yellow blooms giving the already elegant dogwood an even more beautiful look in the woodland landscape.

Native Spicebush is an even better replacement for Forsythia

An even better choice than Cornus Mas to replace forsythia is our native Spicebush – often referred to as the “Forsythia of the wilds.” Not only is it covered with soft umbel-like clusters of yellow flowers in early spring like Cornus Mas, Spicebush is an excellent plant for native wildlife, including pollinators and native mammals.

The flowers are followed by aromatic glossy red fruit, and its leaves turn a colourful golden yellow to light up our gardens and lowland woods where it likes to grow in the wild. It is a host plant for both the Spicebush swallowtail and Eastern Tiger Swallowtail.

It grows to between six and twelve feet tall in sun, part shade and full shade making it the perfect under story addition to our woodland. It is not particular about soil feeling at home in dry, moist or wet soil.

The flowers of the Cornus Mas are quite small (5-10 mm in diameter) with four yellow petals, that are produced in clusters of 10-25.

For more information and excellent photos of more mature specimens, check out the Seattle Japanese Garden website.

Be sure to check out my earlier post on Six Dogwoods for the Woodland Garden.

More of my posts on Dogwoods

For more information on Dogwoods, please check out my other posts listed here:

Dogwoods: Find the perfect one for your yard

Flowering Dogwood: Queen of the Woodland garden

Cornus Kousa: Impressive non-native for the woodland garden

The variegated Cornus Mas stands out among the sea of ferns with its brighter foliage that helps it look like its almost in flower all summer long.

Maybe homeowners are unaware of the Cornelian Cherry, or, maybe, the additional cost of the dogwood is too much compared to the inexpensive forsythia shrub.

Trust me, however, if you are looking to take your woodland garden to another level, while still maintaining that early spring shot of bright, cheery yellow in the landscape, the Cornelian Cherry is a much better choice over the old-fashioned forsythia.

To be fair, forsythias are classed as a shrub, whereas the Cornelian Cherry falls into the category of a small tree.

Still, I would think the two plants serve much the same purpose in most landscapes – to add early spring colour in an otherwise drab garden.

The competition ends quickly when, after the forsythia stops blooming and the homeowner is left with nothing but a scraggly green bush.

In the meantime, the Cornelian Cherry’s flowers slowly turn to bright red berries throughout the summer months. Add to that the fact that these red berries are spread along the elegant, horizontal branches of the small dogwood tree.

And, if that is not enough, our variagated Cornus Mas grows up through our massive ostrich ferns brightening the lightly shaded corner of our garden.

The delicate branches of the Cornus Mas rise above the tall ostrich ferns in early summer.

When does Cornelian Cherry flower?

In warmer areas, the Cornelian Cherry can bloom as early as February, but in colder climates (zones 5-6) you can expect yellow blooms in late March or more likely into April and May.

Where does Cornelian Cherry grow?

Growing in zones 5-8, in full sun to partial shade, Cornus Mas is native to Southern Europe and Southwestern Asia.

Can you eat the cherries?

The edible fruits or drupes (fleshy fruits, with a single hard stone, like cherries) are red berries that ripen in mid- to late summer, but are mostly hidden by the foliage. The fruit is edible, olive-shaped and about ½ inch long, they have relatively large stones when ripe and often described as a mix of cranberry and sour cherry. It is primarily used for making jam but also has a reputation in some parts of the world as a fruit used for distilling vodka.

Do birds eat the fruit?

Birds and mammals are also attracted to the bright red fruit that is very tart, but attractive to birds and squirrels as it ripens and falls to the ground.

How to propagate Cornelian Cherries?

Cornelian Cherries are easily propagated from cuttings, but can also be grown from seed.

Are there cultivars of the Cornelian Cherry/Cornus Mas

There are at least three different cultivar available including:

• Aurea that has yellow leaves and flowers with red fruit in late summer.

• Golden Glory which is grown for its abundance of yellow flowers, followed by shiny red berries.

• Variegata grown for its variegated leaves that help light up shady areas of the garden. It also sports the glossy red fruit in late summer.

Pagoda Dogwood: Shade-loving native tree for woodland, wildlife

The Pagoda Dogwood or Cornus Alternifolia is a small native tree or shrub that is perfect for a woodland garden and vital to native wildlife, including birds, caterpillars, insects and mammals. It’s also an elegant, multi-layered tree with a beautiful horizontal habit that works as well in a woodland garden as it does in a Japanese inspired garden.

My love affair with dogwoods actually had its roots not with the showy Flowering Dogwood, but with a lesser known native dogwood – Cornus Alternifolia.

You may know it as Pagoda Dogwood or Alternate-Leaved dagwood if you know it at all. Trust me, if you don’t already know about Cornus Alternifolia, you need to get to know this outstanding little gem of a dogwood. My first experience with it was in our previous home where I planted it outside the office window where I could admire it and its avian visitors spring, summer, fall and throughout the winter.

When we moved to our current home more than 23 years ago, the first tree/shrub I planted was another Pagoda Dogwood, and it continues to impress me to this day with its longevity and strong presence in the garden throughout the seasons.

Be sure to read my article on six of the best native dogwoods.

The native to the Carolinian forest is not always the showstopper, taking a back seat to the more showy Flowering Dogwood, but it’s like a younger sibling fighting hard to unseat Cornus Florida for top spot in the forest.

Cornus Alternifolia (Pagoda Dogwood) is a semi-colonizing 25-foot tall shrub or tree with a strong horizontal layering habit, that spreads by both seeds and layering. It grows in partial shade to full sun in moist, well-drained rich loamy, slightly acid soil.

This little chipmunk wasn’t waiting around for the birds to help themselves to the berries of the Pagoda Dogwood in the backyard. She searched out the ripened blackish berries as soon as they were ready for eating.

How big do Pagoda Dogwoods get?

Cornus Alternifolia or Pagoda Dogwood is a small tree or shrub reaching anywhere from 15-25 feet tall with an impressive spread of between 12 to about 32 feet.

Is the Pagoda native to areas of Ontario and the United States?

It’s native to Ontario and Northeastern United States and elsewhere including parts of the upper Midwest and even into parts of Minnesota.

How can you tell a Pagoda Dogwood?

In nature, you can spot a Cornus Alternifolia by its characteristic horizontal branching habit, creamy umbrel-style flowers, black berries and deeply veined, ovate leaves that turn a lovely shade of redish, orange in fall. Also, its Latin name is derived from the alternate position of the leaves on the stems.

Without a doubt, however, its most impressive feature is its truly elegant horizontal branching habit that gives the tree its beautiful shape in the woodland garden and makes it a valuable addition to a Japanese-style garden.

More of my posts on Dogwoods

For more information on Dogwoods, please check out my other posts listed here:

Dogwoods: Find the perfect one for your yard

Flowering Dogwood: Queen of the Woodland garden

Cornus Kousa: Impressive non-native for the woodland garden

Our Pagoda Dogwood in full bloom. Each of these florets will form berries that are particularly attractive to a host of birds from Bluebirds to Cardinals. The berries start off green and eventually turn a blackish-blue as they ripen.

When does the Pagoda Dogwood flower and produce berries

The Pagoda Dogwood’s creamy, umbrel-like flowers bloom from May through July depending on location, followed by clusters of black fruit in July that attract a host of birds from the Eastern Bluebird to Scarlet Tanagers just to name a few. Chipmunks and red squirrels are also regular visitors and will strip the berries as fast as they ripen.

Pagoda Dogwood berry clusters are loved by both birds and chipmunks in our yard.

What is a Pagoda Dogwood’s Lifespan?

Our original Cornus Alternifolia is still doing well after more than 23 years in the garden. It’s no surprise that it is still gracing our woodland considering the longevity of these tough little trees. Pagoda Dogwoods can live between 50 - 150 years old so there is a good chance it will still be around for a few years yet. A second Pagoda Dogwood was planted a few years ago in the understory of two very old crabapple trees located not too far from the original Pagoda.

What birds are attracted to the Pagoda Dogwood?

The list of avian visitors is almost endless and include the highly sought after Eastern Bluebird, a variety of Vireos and Thrushes as well as Cedar Waxwings, Gray Catbirds, Cardinals, Scarlet Tanagers, Eastern Kingbirds, Rose-Breasted Grossbeaks and Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker.

Our original 23-year-old Pagoda Dogwood in spring bloom showing off its multitude of blooms. The umbrel-type, creamy flowers are not the show stoppers of the more showy Flowering Dogwoods, but they hold their own in the woodland as a lovely understory tree.

The same 23-year-old Pagoda Dogwood in its fall coat.

Is Cornus Alternifolia a host plant?

The Pagoda, like most native plants, is a host plant to a number of Lepidoptera (caterpillars or larvae of moths and caterpillars) including: The Fragile Miner Bee, Summer Azure butterfly, the impressive Cecropia Moth, Fragile White Carpet Moth and Unicorn Caterpillar.

What Native bees does Cornus Alternifolia attract?

The spring and summer flowers provide nectar and pollen for a number of our native bees including: The bright flourescent Sweat Bees, Miner Bees, Masked Bees and Hover Flies.

What other species is the Pagoda Dogwood related to:

Dogwoods represent a large species ranging from the impressive and equally beautiful Flowering Dogwood (Cornus Florida) to the diminutive Bunchberry (Cornus Canadensis) with its familiar dogwood flowers in minature form growing in large swaths as a ground cover. Other related species include: Red-Osier Dogwood, Rough-leaved, Grey, silky and Round-Leaved.

What cultivars are available for the Pagoda Dogwood?

Using the native, non-cultivar or species tree/shrub is always a solid choice if you want to attract or provide food for the largest variety of wildlife in your garden. There are, however, popular cultivars of Cornus Alternifolia if you are looking for specific traits in the plant.

Golden Shadows: This brightly-coloured variety (zones 3-8) from Proven Winners sports variegated leaves that help the plant stand out in a shady area of the garden where it reaches heights of 10-12 feet with an equal spread. The highly successful company describes the plant as: “bright yellow with a splotch of emerald green in the cenre, taking on pink tones on the new growth in cool weather. Spring sees the plant graced with lacy white blooms. Beneath all this beauty lies a tough North American native that can grow in many difficult conditions; Golden Shadows Pagoda Dogwood is especially noteworthy for its ability to thrive in light shade, its bright foliage bringing colour and beauty to otherwise dim sites.”

C. alternifolia 'Argentea' is known as silver pagoda dogwood and is similar to Golden Shadows but sports a green and white variegation rather than the green and gold.

Cornus controversa: Sometimes called the Wedding Cake Tree, it is a spectacular, extremely showy giant pagoda dogwood with a mature height of 60 feet. When this tree is in flower it is simply a spectacular site. Grows in zones 6-9 and is the winner of the prestigious Award of Garden Merit from the Royal Horticultural Society.

Six Dogwoods for the Woodland Garden

Six Dogwood species that make their home in our Woodland garden. From the ground cover Bunchberry, to shrubs and small understory trees like the Pagoda Dogwood and Cornelian Mas. Dogwoods offer great alternatives and are a valuable addition to any wildlife, woodland garden.

Ground covers, small shrubs and trees for everyone’s taste

If you’ve been following this blog, you’ll know that I have a soft spot for Dogwoods – big and small.

I consider them to be the perfect genus providing everything from the perfect ground cover for shade, to shrubs and mid-size trees that create an anchor for the understory layer. Add to this, outstanding spring flowering followed by a profusion of berries that birds, butterflies, native bees, chipmunks, squirrels and a host of other mammals can’t get enough of, and you’ve got yourself the perfect group of plants for the woodland/shade garden.

Oh, and throw in some spectacular fall foliage just to round out the reasons every garden needs to have plenty of Dogwoods.

Buying plants from local nurseries is the common method of obtaining these plants, but be aware that many of Dogwoods have been cultivated and may not provide all the benefits that the straight species provide to our native wildlife.

This flowering dogwood shows off its splendid fall colours in the back garden.

This article should help provide readers with a better understanding of the various dogwoods available. Most of the links in the article will take you to more extensive posts I have written about the individual plants, trees and shrubs.

It’s always best to use a native variety which are more beneficial to local birds, insects and pollinators.

Our Woodland garden boast six varieties of Dogwood. Let’s start with the smallest.

This detailed native dogwood poster is best viewed on a tablet or desktop and was created by Justin Lewis

Cornus Canadensis: A native ground cover for a shady area

Often called Bunchberry (link to my story on this native ground cover) or creeping dogwood, this perennial creeping rhizomatous ground cover grows 3-6 inches high and is topped by a blossom that looks very much like a miniature version of the familiar Dogwood tree (Cornus Florida) blossom. The flower cluster, held on a short stalk just above the leaves, resembles a singe large flower.

Not unlike the tree form of Dogwood, the flower is followed in the fall by a cluster of bright red berries surrounded by wine-red foliage.

More of my posts on Dogwoods

For more information on Dogwoods, please check out my other posts listed here:

Dogwoods: Find the perfect one for your yard

Flowering Dogwood: Queen of the Woodland garden

Cornus Kousa: Impressive non-native for the woodland garden

Bunchberry: The ideal native ground cover

Bunchberry in bloom in the woodland garden.

It grows in sun, part shade to full shade in zones 2-6 and likes to grow in a cool, damp acidic soil. It will often form clonal colonies under pine trees. Amending the soil using peat moss and mulching with pine needles yearly is a good idea if you plan to grow this ground cover.

Bunchberry can be found growing wild in coniferous and mixed woods, cedar swamps and damp areas across North America to Greenland and northeast Eurasia.

Although it can be hard to find at most regular nurseries, higher-end nurseries in the growing zones will either carry it or can often obtain it for you.

Ontario Native Plants now carries the plant in limited quantities so put in your order early to ensure you can get some. If you are in Ontario, be sure to check out my full story on Ontario Native Plants.

This is a new addition to our Woodland garden. I earlier experimented with it in three very different spots in the garden, but all three plants failed. I now have several plants growing on the side of our property in an area where they should thrive.

The Pagoda Dogwood in bloom with its creamy white flowers that are followed with an abundance of berries that birds and other wildlife love.

Cornus Alternifolia: Perfect small tree for the woodland/wildlife garden

This common under story species that is often called Pagoda Dogwood (Link to my full story) is the tree/shrub that got me started down the Dogwood trail. We planted one at our former home right outside the office window and I absolutely loved that small tree. It was also the first tree we bought when we moved to our current home 23 years ago. That tree has become known as our “Africa tree” because of its flat-topped appearance and the fact the deer have eaten it so perfectly from the bottom up.

The tree’s attractive horizontal branching habit creates a lovely tiered look as it ages. Large clusters of cream flowers appear in spring or early summer (very unlike the familiar Cornus Florida bracts) followed by dark blue-black berries by mid summer. What’s not to love?

It grows to about 20-30 ft tall high, preferring moist soils in partial shade. Unlike other native dogwoods, this species has alternate rather than opposite leaves, hence its name. They grow naturally in rich, deciduous and mixed woods, in zones 4-8 often found on forest edges, along streams and on swamp borders.

The bracts of the Cornus Florida Dogwood are beautiful even from below.

Cornus Florida: Crown jewel of the Carolinian forest

In my opinion, the Flowering Dogwood (link to my post on best Carolinian under story trees) is the queen of the under story trees in a Carolinian Woodland setting.

Here is a link to my full story on the Flowering Dogwood or Cornus Florida.

The horizontal branching of the Cornus Florida shows off its spring bracts above the blue jay.

When it comes to the perfect tree, it’s a tough one to beat. Its spectacular in spring flower but still stunning when not in flower. Cornus Florida grows to about 20-40 ft as a single or multi-trunked tree with outstanding showy, white and pink spring blooms, with a horizontal branching habit, red fruit and scarlet autumn foliage.

The flowers, which are actually bracts, can grow to 3 inches wide and attract butterflies and bees. The fast-growing trees prefer partial shade but can tolerate full sun if they are kept moist. They are native to the eastern United States and the Carolinian Canada Forest in southern Ontario and throughout zones 5 through 9. Although they may seem like the perfect tree, they are subject to anthracnose – a fungal disease that causes leaf spotting and twig dieback. Diseased twigs and branches should be pruned off and disposed. Ensuring good air circulation to keep the foliage dry and maintaining moisture in the soil throughout the summer will help reduce exposure to the fungal disease.

The bright red fruit of the Cornus Kousa.

Cornus Kousa: Popular non-native with spectacular summer show

A close second to the native Cornus Florida is the Kousa dogwood, which also goes by the names of the Chinese, Korean and Japanese dogwood. One of the advantages this tree offers over Cornus Florida is the fact it is resistant to the common dogwood anthracnose disease. As a result, it is being used more and more as an ornamental tree in areas where the disease is common.

The Kousa dogwood is a plant native to East Asia but is widely available where the Florida Dogwoods grow. It’s upright habit, later-flowering (about a month later) and pointed rather than rounded flower bracts makes it an ideal companion to the Flowering Dogwood.

Be sure to check out my full story to get much more detailed information on the Cornus Kousa Dogwood.

Although it can be incredibly showy in its own right, the Kousa dogwood tends to flower after the leaves come out rather than the Florida Dogwood that blooms prior to the tree leafing out, Combine both trees in your understory and you have glorious Dogwood flowers from late spring well into summer. Both species have a number of cultivars that include variegated leaves that add to their showiness in the right situations.

Cornus Mas: Early yellow-flowering tree for the shade

Often referred to as the Cornelian-cherry dogwood, this family of dogwood is native to Southern Europe and Southwestern Asia. It can be grown as a small tree or medium to large deciduous shrub with small yellow flowers produced in clusters along the branches either in late winter or more likely early spring in North America.

Here is a link to my full story on Growing Cornus Mas in the woodland.

The fruit has many uses including as an herb and is used widely for jams and and in some European countries distilled to make vodka. In the Woodland, the large oblong red fruit is a favourite of many birds and mammals.

In my garden, the Cornus Mas is one of the earliest flowering trees that blooms alongside the forsythia. I suspect many people mistake the small tree for a forsythia bush.

In our garden, we have a variegated form that grows up through our large ostrich ferns, and provides a spot of colour is a sea of green. The Cornus Mas in our garden is a small tree/shrub and is one of the few variegated plants in our entire Woodland garden.

Cornus sericea: Popular red-twigged shrub ideal for winter interest

Commonly named the Red-osier Dogwood, it is probably one off the most common shrubs in garden landscapes providing much-needed winter interest for gardens, especially when planted in large clumps. Often mistaken for the popular Asian equivalent Cornus Alba, with its variegated leaves which is seen in gardens everywhere.

Cornus sericea is native throughout parts of North America from Alaska east to Newfoundland.

In the wild, it most often grows in dense thickets in very moist areas. Our native species have dark green leaves that turn bright red to purple in fall. The spring flowers are creamy clusters and the fruit are a cluster of small white berries.

These Dogwoods not only look good, the native varieties provide multiple sources of food for backyard birds. While I get great enjoyment from my bird feeding stations, providing natural food sources to our feathered friends is always the goal we should aspire to in our gardens.

I have written a comprehensive post on feeding birds naturally. You can read about it here.

If you are interested in exploring Dogwoods further, check out Dogwoods: The Genus Cornus. This is another outstanding gardening book from Timber press.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

Native moss in our gardens

This page contains affiliate links. If you purchase a product through one of them, I will receive a commission (at no additional cost to you) I only endorse products I have either used, have complete confidence in, or have experience with the manufacturer. Thank you for your support.

Now you can turn your yard into a Certified Firefly Habitat

Now homeowners, groups and organizations can get their properties certified as Firefly habitats and purchase a sign to announce their commitment to ensuring firefly habitat.

What you can do to save fireflies

Fireflies should not just be a childhood memory when we sat out on the porch and watched fireflies flicker all around us.

And they don’t have to be. Even if you live in the heart of an urban area you can take steps to make fireflies a part of your life again.

Or, maybe fireflies never stopped being a part of your life. Maybe you have been doing everything right and still enjoy plenty of the little insects lighting up your summer evenings.

Either way this is good news for you.

Firefly Conservation and Research, an organization committed to saving fireflies worldwide, has just announced a new program for homeowners and other groups such as schools to have their properties approved as “Certified Firefly Habitats.”

For homeowners who want to bring back fireflies to their properties, the program will guide you to create the right habitat to encourage fireflies and encourage you to reach the goal of creating a Certified Firefly Habitat.

And, for those homeowners or groups who have already been working hard to create these favourable habitats, they are more than welcome to share their hard work with neighbours in the form of a sign that can be displayed on your property.

Check out my earlier post on attracting fireflies to your backyard.

How to get your Certified Firefly Habitat

Make a firefly haven in your own yard and join the thousands of others who have done the same. Join individuals and organizations who have committed to providing the essential elements needed to create and sustain a healthy habitat for adult and larval fireflies.

Proudly display this sign to demonstrate your commitment to protecting firefly habitat. The sign is made of recycled aluminum, is easy to read and waterproof. The size is 9″ x 12′′. “Made in the USA.” Exclusive.

The organization behind the habitat certification

Firefly Conservation & Research is a nonprofit organization founded in 2009 by Ben Pfeiffer, a firefly researcher, and Texas-certified master naturalist with a degree in biology from Texas State University.

Ben points out that fireflies need protection now. “Across the United States and worldwide, rapid and large-scale changes to our lands and watersheds mean fireflies are losing the habitats they once knew. Every step we can take to protect land for the fireflies to thrive is a step towards a literally ‘brighter’ future for new generations to enjoy,” he writes on his website Firefly.org.

“Join us in our mission to help to certify habitats, backyards, and nature preserves to provide a permanent place for fireflies to exist,” he adds.

• If you are considering creating a meadow in your front or backyard, be sure to check out The Making of a Meadow post for a landscape designer’s take on making a meadow in her own front yard.

“The Certified Firefly Habitat program is a first of its kind certification program to address the issues leading to declining habitat for fireflies. Ben will teach participants how to curate their habitat so that it provides all of the elements needed for fireflies to establish an existing and growing population on their land.

Those wishing to start the certification program will be asked to provide the following elements on their land:

Providing undisturbed cover for adults and glowing larvae

Encouraging plant diversity to preserve soil moisture

Reducing Light Pollution

Restricting Pesticide Usage

A certification guide will be available for you to download to help guide you in this process. This checklist will help you meet all the requirements necessary to provide firefly habitat.The guide will also teach you about:

The Firefly Life Cycle

What kinds of fireflies you are protecting

How habitat degradation and loss affect fireflies

What invasive species do to firefly habitat

Methods to manage your habitat from surveying methods, documentation, putting up protective barriers to prevent trampling.

Other insightful and creative ways to protect fireflies beyond just your land.

Wild Bergamot: Easy-to-grow native wildflower and pollinator magnate

Wild Bergamot is a valuable native wildflower that should be in every garden, both for its beauty and its importance to wildlfe from native bees to moths and butterflies.

If anyone needs an example of a native wildflower that combines beauty, vigour and is a magnate for pollinators, they need look no farther than Wild Bergamot.

Add to that the fact, Wild Bergamot is one of the easiest wildflowers to grow, combining masses of beautiful purple blooms that last from mid to late summer.

Wild Bergamot, sometimes referred to as Bee balm, is a name that’s also given to the red species of bergamot in the eastern U.S.

The multi-branched, clump-forming perennial has flowers that are normally in 1 terminal cluster, subtended by many small leaves. Floral tubes are about 1.5 inches long and end in two lips – the lower broad and recurving, the upper arching upward with stamens prodruding in lavender, lilac, or rose.

Be sure to check out my complete article on the 35 best wildflowers for the woodland garden.

What to plant with Wild Bergamot

The plants, often called Horsemint, work nicely with yellow flowers like Black-Eyed Susans, tall tickseed, goldenrod and yarrow, as well as Smooth Oxeye daisies, Purple Coneflower, Joe Pye Weed, Whorled Milkweed, Michigan Lily, Culver’s root and Flowering Spurge. Tuck them in alongside both Little and Big Bluestem, where the purple flowers are striking against the bluish foliage of the native grasses.

How to grow Wild Bergamot

Monarda Fistulosa is an easy-to-grow, 2-4-foot tall colonizing shrub that is as happy spreading by seed as it is by underground rhizomes. Grow it in full or partial sun, in moist to slightly dry soil in sandy loam or even clay loam.

Native wild bergamot is an excellent plant to attract a host of pollinators from native bees to butterflies.

When does Wild Bergamot bloom

Depending on where you are located, Wild Bergamot’s soft mauve or purple flowers will provide multiple blooms in the summer months, as early as May in some areas but primarily June, July and August, just when butterflies, moths, hummingbirds and and native bees need them most.

What flowers are related to Wild Bergamot

Wild Bergamot is closely related to pollinator standouts Scarlet Beebalm, Spotted Beebalm and the hybrid Purple Beebalm

Wild Bergamot’s leaves and flowers have a sweet fragrance and are actually edible. The flowers can by used both as cut flowers and in bouquets.

Powdery mildew can be a problem so it’s best provide water at the root zone rather than using overhead watering systems that tend to leave water on the leaves.

What pollinators does bee balm attract?

Don’t be surprised to see Ruby-Throated Hummingbirds flocking to your Wild Bergamot for a never-ending supply of nectar.

The Hummingbirds will be joined by Sphinx moths (often mistaked for Hummingbirds) a host of butterflies including those in the swallowtail family, Cabbage whites and skippers, including the Silver-Spotted skippers.

Native bees – including the Dufourea Monardae, a North American species of sweat bee in the Halicidae family – the Bumble bees, Sweat bees, Leaf-Cutters and Miner Bees are also attracted to the plants, which are members of the mint family. Hover and Bee flies as well as Vespid Wasps are also regulars to the plants.

What eats Wild Bergamot

Don’t worry if you see some of the leaves being eaten. A number of moths, including the Raspberry Pyrausta, Hermit and Gray Marvel moths use the plant as a host plant in their larvae stage.

The Horsemint Tortoise Beetle is a regular at the dinner table where they eat bergamot and other members of the genus Monarda.

In conclusion: A native wildflower we all need to grow

Native Wild bergamot is one of the real winners in the world of wildflowers. Every garden needs to grow at least one clump of these valuable landscape plants that offer long-lasting beauty in combination with a benefit to wildlife that is hard to underestimate.

Three great woodland gardens in Canada

Canada boasts its share of woodlands both in its National Park system as well as its extensive series of provincial parks and conservation areas, but it’s the public gardens that makes areas from east to west that makes it a tourist destination. Check out three of Canada’s finest woodland gardens and public gardens.

Canadian Travel Destinations: Put Hamilton and Toronto Botanical Gardens and Stanley Park on the list

The Royal Botanical Gardens is a gem in the heart of one of Canada’s most highly populated areas – less than an hour outside of Toronto and about the same distance to the Niagara region and the U.S. border.

The five cultivated garden areas, including the outstanding sunken rock garden and tea house, and its impressive rose and iris collections, get much of the publicity as the gardens come into bloom over the course of the summer. Although these more formal gardens are impressive, it’s the more wild, Woodlands and natural areas of the gardens that are slowly gaining recognition in social media circles.

Maybe it’s the bald eagles, ospreys and massive herons (both Great Blue and Great Whites) that have returned to the area after years of being absent. Maybe it’s the beavers that seem to pose for nature photographers, the coyotes, foxes or friendly chickadees that don’t miss a chance to land on visitors’ outstretched, seed-filled hands. Maybe it’s the massive boardwalks that take you through the heart of marshes, the spring ephemerals that brighten the woodlands in spring, or the spectacular colours of the woodland garden in the fall.

It’s probably a combination of all of these natural features that are getting the attention of nature lovers looking for an experience in the outdoors, away from the worries of Covid.

If you are looking for more travel destinations, check out my article on Five of the best Woodland Gardens to visit in the United States.

I’m lucky to live just 15 minutes from The Royal Botanical Gardens, or the RBG as locals call it.

A Cherry Tree in bloom at the Royal Botanical Gardens Arboretum, one of several gardens at the southern Ontario tourist destination.

The Royal Botanical Gardens is massive: 5 cultivated Garden areas, 27 kms of nature trails, 2,500 plant species, 2,400 acres of nature sanctuaries and 300 acres of cultivated garden.

Several years ago, I was part of a group of five photographers lucky enough to work with the RBG to create photo cards and posters of its outstanding gardens. In those days, the natural areas were less known but still offered nature photographers and lovers a taste of what was to come.

Today, the “Woodland gardens and nature trails feature more than 27 km of nature trails and include four main trailheads, as well as two canoe launch sites,” the gardens’ website states.

“The 1,100 hectares is dominated by 900 hectares of nature sanctuaries enveloping the western end of Lake Ontario. These lands form a Nodal Park within the Niagara Escarpment World Biosphere Reserve (UNESCO) and the heart of the Cootes to Escarpment Ecopark System. With more than 750 native plant species, 277 types of migratory birds, 37 mammal species, 14 reptile species, 9 amphibian species and 68 species of Lake Ontario fish, the area is an important contributor to ecosystems that span international borders.”

Here are a few areas to focus on:

The graphic above shows the extensive trail system through the woodland and over marshes via an extensive boardwalk system.

Trail Destinations: Hendrie Valley is home to lots of interesting trails and lookouts! Here are 5 key destinations marked by number on the map above.

1) South pasture swamp: An oasis for endangered species, this spring-fed oxbow pond is home to beaver, muskrat, Virginia rail and wood duck. Work to restore this site began in 1994 as part of Project Paradise.

2) Grindstone Creek: With three pedestrian bridge crossings and a creek-side trail, the valley provides an intimate connection with the creek. Seasonal fish spawning runs include herring and spottail shiner in the spring and salmon in the fall.

3) Snowberry Island: Halfway along the Grindstone Marshes Boardwalk, Snowberry Island sits five metres high in the floodplain. Named after a species of plant that grows there, the island is a block of uneroded creek valley soil called a knoll.

Grindstone Creek Delta: Located at Valley Inn trailhead, it’s both the site of an ambitious restoration project and stop-over point for migratory waterfowl. More than 100,000 Christmas trees form the foundation for the restored river banks of Grindstone Creek — these protect the marsh areas by preventing carp from entering.

An example of the boardwalk through the trails of the Royal Botanical Gardens.

The Royal Botanical Gardens on the Hamilton/Burlington border is truly a weekend travel destination for anyone living within a few hours of the massive gardens. It is truly a family destination with a host of kid-friendly features and activities.

For garden lovers, the RBG is much more than a weekend travel destination. It’s actually an ideal base to explore all that the Niagara Region – featuring wine country, picturesque Niagara-On-The-Lake and the Falls (one-hour away) – and the metropolitan city of Toronto (an hour away in the other direction), has to offer travellers.

The Woodland Walk and Bird Habitat gardens that greet visitors to the Toronto Botanical Gardens and Edward’s Garden in the heart of Toronto.

Toronto Botanical Garden’s Woodland Walk and Bird Habitat

About an hour’s drive down the highway from Hamilton/Burlington’s RBG is Toronto’s own Botanical Gardens and Edward’s Garden, located in the heart of the city.

Here you will find a wonderful Woodland and bird garden introducing you to the much larger and more formal Edwards Gardens operated by the Toronto Botanical Gardens. Edwards Gardens, that sits adjacent to the Toronto Botanical Garden, is a former estate garden featuring perennials and roses on the uplands and wildflowers, rhododendrons and an extensive rockery in the valley. On the upper level of the valley there is also a lovely arboretum beside the children’s Teaching Garden.

The Woodland Garden design combines a native woodland and prairie garden, providing a year-round habitat for birds and other wildlife.

The garden’s roots go back to 2009, when staff together with numerous volunteers and members of the industry came together to begin working on the garden.

Many of the plants are native to the Canadian Carolinian Forest. (see my earlier article on the Carolinian Forest). The space is an evolving garden, being planted over several years, that will “serve as an outdoor classroom to educate, both passively and actively; to promote sustainability, conservation and biodiversity; and to showcase horticulture.”

A few highlights from the TBG website:

This garden invites and welcomes the public and members into the gardens of the Toronto Botanical Garden and Edwards Gardens. It is a reflection of the beauty and gardens that lie beyond the parking areas.

The garden helps beautify the typical urban landscape at the intersection at Lawrence and Leslie.

Native plants–where possible–have been carefully selected to reflect the Carolinian Forest, providing food and shelter for birds and other wildlife

A natural wood chip path leads the visitor from the busy intersection through the dappled shade of the open woodland to the masses of perennials, ornamental grasses and other seasonal plants in the Entry Garden.

Stanley Park is an impressive example of a natural woodland garden.

Stanley Park: Canada’s ultimate woodland garden

I have had the good fortune to spend a day at Vancouver’s spectacular Stanley Park several years ago. It was a misty morning adding to the mystery of this wonderful landscape.

We visited Stanley Park many years ago and I don’t remember much accept that it was one of the highlights of my life and probably, together with a visit to Butchart Gardens in Victoria, B.C., turned me into a woodland garden enthusiast. There is something about the landscapes of the pacific northwest that you just can’t help but fall in love with.

If you travel to Canada’s far west, try to take in Vancouver Island’s Butchart Gardens. A spectacular 55-acres of sunken gardens boasting 900 plant varieties, 26 greenhouses and 50 gardeners, Butchart has enjoyed more than 100 years as a must-see garden near Victoria, B.C.

Salisbury Woodland Gardens located within the massive Stanley Park is a an attractive green space, planted in the mid 1930’s to serve as a public recreation area as well as shelterbelt for Stanley Park Golf Course. The woodland contains many native and exotic trees and shrubs. Winding footpaths take visitors through the garden over brooks.

The woodland, which has been undergoing renovation since 2006, was designated as a County Biological Heritage Site in 1993 for its epiphytic flora. Wildlife includes birds such as kingfishers, treecreepers and woodpeckers. The site also supports colonies of pipistrelle bats, dragonflies and butterflies such as orange tip and peacock.

In conclusion

The public gardens, as well as the national and provincial parks, and conservation areas in Canada provide visitors with incredible experiences in nature. As Covid winds down and families look to escape either on quick weekend vacations or day visits, these gardens and natural areas offer some of the safest ways to plan a vacation.

Gardener’s Supply Company: Success grows out of passion to improve the world

Gardener’s Supply Company is a United States based garden nursery that operates a web based on-line store and printed catalogue. The company is employee owned and goes to great lengths to promote its mission to make the world a better place through gardening.

What makes Gardener’s Supply Co. so special?

Growing a garden takes time, patience and a love for what you are doing and trying to accomplish. For many, it’s a family affair where we work together for years to create the landscape of our dreams.

Over time and hard work, our gardens take shape and that dream becomes a reality.

I can’t help but think the same sense of accomplishment of creating that garden of our dreams is the same feeling staff of Gardener’s Supply Co. (Link to website) experiences with their genuine success. Since 2009, the Burlington, Vermont company, that has become synonymous with gardening at its finest in the United States, has been 100 per cent employee-owned.

Why should we care?

Like we gardeners in our own yards, staff are passionate about ensuring the commercial and mail-order garden nursery grows into a success. The company’s impressive website clearly illustrates both a love for everything gardening and a wish to share that enthusiasm and success with gardeners.

“Through employee ownership we remain passionately committed to our founding vision – to spread the joys and rewards of gardening, because gardening nourishes the body, elevates the spirit, builds community and makes the world a better place,” the website states.

A mail order and shopping website just for gardeners

Unlike other massive mail-order firms that offer everything you can think of including gardening accessories, Gardener’s Supply Co. (link to Website) is focused on one thing – gardeners.

Being co-owners means that staff:

care deeply about our customers and their successes in the garden;

sustain a vibrant focus on gardening;

support a strong social mission;

take care of our communities and one another;

and work hard to safeguard the increasingly fragile planet we’ve been entrusted with.

Okay, their hearts are in the right place, but how can they help us and our gardens?

Just one look at their website and I think most would agree that this is no ordinary commercial gardening on-line store and website.

For example, these five galvanized planting pots (above) combine rustic and modern, are the perfect addition to a patio or deck.

Offering everything from essential garden tools to unique garden implements, many that are designed and manufactured in their own facilities, Gardener’s Supply is a website that helps us take our gardens from the ordinary to the exquisite. And it’s not just the products being offered on the website or through the printed catalogue, the garden information on their website is a fount of knowledge for both new and seasoned gardeners.

Browsing the site is akin to wandering through your favourite mega garden store without the crowds.

You will find areas featuring garden supplies obviously, separate areas on Planters and Raised Beds, Yard and Outdoors, Indoor Gardening, your home and kitchen accessories as well areas that focus on seeds – everything from vegetable seeds to seed starting supplies, grow lights and stands.

There is also a separate area just for gift ideas.

Gardener’s Supply on a mission to improve the world

But it’s their focus on creating a better world that is hard to ignore

On their website they provide visitors with the causes the company believes in.

“We’re on a mission to improve the world through gardening. We stand up for our beliefs, give voice to those who can’t, and serve as an ally to gardeners everywhere.”

Just a few of the areas they focus on include: Pollinator protection, youth gardens, soil regeneration and fighting hunger.

Gardener’s Supply helps the hungry

A Garden To Give program, where the company encourages gardeners to grow extra vegetables to donate to the needy through Ample Harvest, is just one example of where the company takes action. Their garden nursery in Vermont also includes raised gardens where all the produce is donated to the needy.

Gardener’s Supply helps pollinators

The company’s extensive information about pollinator protection shows that they are not just paying lip service to the protection of pollinators and not just honey bees.

Gardener’s Supply helps children

When it comes to kids and gardening, Gardener’s Supply not only runs a Kids Club at three of their facilities but provide further information about the importance of gardening for Youth.

(If you are interested in getting your children or grandchildren involved in gardening, be sure to read my article on Why kids need more nature in their lives.)

Back to products, accessories and other fun stuff.

Woodland/wildlife gardeners will first want to go directly to the Yard & Outdoors tab and head over to the Backyard Habitat area of the website where they will find separate areas on Bee Bug & Butterfly Habitats, Beekeeping Supplies, Bird Baths, Bird Feeders, Bird Houses and Songbird Tweets.

The Acorn Bird Feeder alone is simply outstanding.

Much of what they offer is of the highest quality, especially the items they design and build right in their own workshops. They may not be the most inexpensive items you’ll be able to find, but the high quality turns many of the items into garden works of art, or, at least, items you will enjoy for years to come and possibly pass on to your children or family members.

For wildlife enthusiasts, Gardener’s Supply Co. offer a range of bird baths including ones made of copper, butterfly houses, a butterfly puddling stone, oriole feeders, elegant bat houses and hummingbird feeders just to name a few of the treats for woodland/wildlife gardeners.

The home decor tab features everything from boot trays to keep the mess outside, to furniture that helps to bring the outside in. There’s even a heart-shaped concrete table top planter ideal for a miniature succulent display.

I could tell you all about the site, but it’s best that you check it out for yourself.

Does Gardener’s Supply Co. deliver all over the United States?

Yes, Gardener’s Supply Co. delivers to all 48 states contiguous states. (For information, check out the specific information on their website.) Shipments to Alaska, Hawaii must travel by 2nd Day Air (select FedEx - AK, HI). Orders shipping to U.S. Territories travel by parcel post (select USPS-International) and will arrive in two to four weeks.

Note: At the present time, Gardener’s Supply does not ship to addresses outside of the U.S. and its territories including Canada and the United Kingdom.

Five of the best woodland gardens in the United States

Five of the best woodland public gardens in the United States you need to visit. It might be a mini vacation or just a drive down the road, but it’s the perfect time to plan a garden destination vacation. Here are five of the best.

Garden destination vacation is perfect for landscape design ideas

Now that we have hopefully seen the end of the worst Covid can send our way, more and more people are planning family vacations.

Many may hesitate to board a plane or cruise ship for a traditional vacation, but may be open to the idea of a driving or mini weekend vacation, especially one that involves being safely outdoors in nature.

Now is the perfect time to consider planning a garden destination vacation by visiting one or more of the many public gardens that offer a safe, outdoor experience where you can explore some of the best garden designs and take home a wealth of knowledge and ideas to use in your own gardens. Garden destination vacations can be as simple as a self-guided walk in the woods or as entertaining and informative as signing up to have a professional guide lead you through the garden experience.

I’ve put together a list of five of the best woodland gardens in the United States to get readers thinking about visiting a local or nearby garden, either as a weekend adventure or as a side excursion during a traditional week-long vacation. There are gardens stretching from New England to Texas and a few in between.

If you are looking to travel to Canada for vacation, be sure to check out Three of the Best Woodland gardens in Canada.

Native Plant Trust (New England Wildflower Society) owns and operates Garden in the Woods, an outstanding natural woodland garden that offers visitors both spiritual and educational experiences just 20 miles from Boston.

How close is Garden in the Woods to Boston?

Garden in the Woods is a 45-acre, magical woodland that showcases the natural beauty of both the New England landscape and, most importantly, its native wildflowers, plants and trees. It’s open to the public through October, if you want to explore the colours of fall while visiting Boston.

Located about 20 miles west of Boston, (in Zone 7A) the massive, naturalistic woodland sculpted by retreating glaciers into eskers, steep-sided valleys, and a kettle pond, is the result of an incredibly dedicated group of individuals who make up the New England Wildflower Society now called Native Plant Trust.

Why should families make Garden in the Woods a travel destination while in the Boston area?

That’s a question I asked Uli Lorimer, Director of Horticulture, at Garden in the Woods.

“Garden in the Woods offers visitors of all ages the opportunity to immerse themselves in the habitats and plants of New England. Exposure to nature, to insects, birds, and the diversity of plant life is crucially important for young children if we hope for them to become the next generation of environmental stewards,” he explains. “The displays include common plants as well as rare, threatened or unusual plants giving the visitor an in depth experience with the diversity of life found in New England.”

What makes Garden In The Woods and its facilities so special to visitors?

“A visitor will immediately sense that this garden is different from other botanical gardens. The way in which the plants are displayed and the experience of walking the trails, the seamless way in which visitors transition from one “garden room” to another is what adds to the unique character of Garden in the Woods,” explains Lorimer. “We offer a wealth of education classes alongside engaging interpretation, affording visitors a chance to learn and grow as they stroll the garden. At our gift shop and plant sale yard, visitors can take home a plant or two to introduce into their own gardens or a tasteful gift, book or memento of the day.”

How can woodland gardeners get the most out of a visit to Garden in the Woods?

“Woodland gardeners are our favorite!, Lorimer explains.

“In order to get the most out of visiting a garden in the Woods, a visitor would need to plan a trip in spring, summer and fall, as the displays and seasonal highlights change. Spending at least 3-4 hours will allow the visitor enough time to leisurely stroll the trails, take notes of the plants and planting combinations they see, to engage with one of the friendly horticulture staff and to feel relaxed and inspired. We strive to offer for sale most of the plants that can be seen in the gardens which helps visiting gardeners act on their new ideas,” he explains.

Uli Lorimer

Special Event: Garden in the Woods is home to a nationally accredited Trillium collection which we celebrate every spring with Trillium Week. This year Trillium Week will be from Monday May 9th through until Sunday May 15th. There will be special garden tours, drop in workshops as well as an evening event planned around the joy of growing Trilliums. Please check out our website https://www.nativeplanttrust.org/events/trillium-week-may-9-15/

Harvard Magazine describes the gardens perfectly: “This “living museum” offers refreshing excursions through New England’s diverse flora and landscapes: visitors may roam woodland paths; explore a lily pond alive with painted turtles, frogs, and dragonflies; or take the outer Hop Brook Trail.”

Garden in the Woods serves as New England Wild Flower Society headquarters

The sanctuary serves as the headquarters of the New England Wild Flower Society who also own the property along with six other botanical reserves in Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire. The Society is probably best know for the fact it produces more than 50,000 native plants annually, grown mostly from seeds found in the wild.

This incredible woodland is, as Harvary Magazine points out in an article: “proof of the Society’s mission to conserve and promote regional native plants to foster healthy, biologically diverse environments.”

In the garden visitors often describe as magical, you’ll find a naturalistic plant collection that showcases New England native plants with complementary specimens from across the country.

Finding inspiration in Garden in the Woods

If you garden in the Northeast part of the United States, this is the place to find inspiration for your own garden and a new appreciation for the varied plant life of the region.

Offering an extensive list of educational classes and field studies to go along with the information provided on its website on ecological gardening, the Woodland garden and website is a must for serious Woodland gardeners and native plant enthusiasts.

“Plants are the foundation of all life. No matter what you want to conserve, whether the interest is in birds, bats, or bugs—they all depend on plants,” executive director Debbi Edelstein told Harvard Magazine. “But people tend to overlook them. People see something green and think it’s good, but they don’t really see the roles that very special individual species play in making everything else healthy.”

Visitors can opt for guided tours through themed plantings including a rock garden, coastal, and meadow gardens as well as the extensive woodland garden.

Early spring (May 5-11) is definitely Trillium time at Garden in the Woods, where they can show off the 26 different trillium species to visitors.

The woodland garden’s peak bloom is in spring and early summer, with the meadow putting on its best show in mid-to-late summer with its abundance of bee balm, Culver’s root, lobelia, and black-eyed Susan, to name just a few of the native species, In the fall, native grasses take the spotlight in the meadow garden along with asters and goldenrods.

One need only look at the extensive trail system on the website to appreciate the vastness of this incredible jewel. If you are thinking about going, you can download a map showing Garden in the Woods’ extensive trail system to plan out your visit before you even leave your home.

If the seafood, Red Sox or tourist attractions in the Boston area are not enough to get you to make Bostonyour summer destination, surely Garden in the Woods will be the attraction to get garden tourists outside to experience nature and scoop some ideas for their own gardens.

For more on this spectacular garden destination, check out the article in Harvard Magazine on Garden in the Woods.

Garvan Woodland Gardens is a destination the entire family will enjoy from children who will be attracted to the Adventure garden, to adults enjoying the outstanding gardens and unique features.

Garvan Woodland Gardens: A must visit for the whole family

Garvan Woodland Gardens, the botanical garden of the University of Arkansas, ( zone 6B, 7A) has a mission to preserve and enhance a unique part of the picturesque Ouachita Mountains of Southwest Arkansas.

Its success stems from the perfect combination of beautiful gardens, elegant structures and landscaping details that celebrates the natural beauty of the Woodland Gardens: featuring a canopy of tall pines that provide protection for delicate flora and fauna, gentle lapping waves that unfold along the 4.5 miles of wooded shoreline, and rocky inclines.

Woodland gardeners will be particularly attracted to the Hixson Family Nature Preserve encompassing 45 acres of natural Ouachita woodland, nestled under a towering canopy of oak and cypress trees, while kids will want to spend time at the Evans Children’s Adventure Garden.

A garden for the kids

Families with children will undoubtedly gravitate toward the Evans Children’s Adventure Garden that offers 1.5 acres of fun tied into natural outdoor education at its finest.

(Here is a link to my article on why kids need more nature in their lives)

The interactive garden features more than 3,200 tons (or 6.4 million pounds) of boulders positioned to encourage exploration of the natural environment. Add to that a 12-foot waterfall that cascades over the entryway and an easily accessible, man-made cave, where children can discover “ancient” fossils. The garden also features a bridge constructed from wrought-iron “Cedar tree branches” and a maze of rocks that lead down to a series of wading pools.

Parents can enjoy a bird’s eye view of their children at play from a 450-foot long, 20-foot tall elevated walkway that also provides scenic vistas of Lake Hamilton and the surrounding woodlands.

Garden beginnings

The Garvan Woodland Gardens, a gift from local industrialist and philanthropist Verna Cook Garvan, also provides visitors with a location of learning, research, cultural enrichment, and serenity in addition to a place to develop and sustain gardens, landscapes, and structures of exceptional aesthetics.

From the dynamic architectural structures to the majestic botanical landscapes, Garvan Woodland Gardens offers breathtaking sights (and fantastic photo opportunities) at every turn.

Hixson Family Nature Preserve

The Hixson Family Nature Preserve encompasses 45 acres of natural Ouachita woodland where visitors can take in the more than 120 species of birds, including bad eagles, pileated woodpeckers and the diminutive tufted titmous along with the long list of fauna that call the woodland home. (Check out this link on attracting the Tufted Titmouse to your garden.)

The Birdsong Trail is a 1.9 mile Birdsong Trail offers resting benches for watching the birds feed at special stations and enjoying some of the best vistas of Lake Hamilton in Hot Springs.

Visitors to the preserve learn about the woodland environment from educational displays placed along the adjoining Lowland Forest Boardwalk – where visitors learn about the environmental benefits of trees and forest cover.

The woodland refuge, nestled under a towering canopy of oak and cypress trees, is also home to the Shannon Perry Hope Overlook, a secluded site for reflection.

Don’t miss out these features at Garvan Woodlands

Millsap Canopy Bridge: Stretching two stories above the forest floor and spanning 120 feet, the serpentine-shaped Millsap Canopy Bridge is one of the most exciting pedestrian structures in the region. Its gently curved walkway winds through a woodland paradise of pools, cascades, and verdant plantings nestled in a ravine christened Singing Springs Gorge. Seasonally, the site offers a showy display of cinnamon ferns, Tardiva and oak leaf hydrangeas, delicate dogwoods and a collection of heat-tolerant rhododendrons.

The Perry Wildflower Overlook: provides sweeping lake views on the 1,500 square-foot flagstone terrace overlooking a one-acre planting of more than 40 different varieties of wildflowers, with new ones added each spring.

Bob and Sunny Evans Tree House: The new centerpiece of the Children's Garden, The Tree House is suspended within a group of pines and oaks, bending easily between them. The theme is the study of trees and wooded plants, drives both the form and program of the structure. The tree house is part of an ambitious plan to bring children back into the woods, the tree house uses a rich visual and tactile environment to stimulate the mind and body, while accommodating the needs of all users.