Mulch Mania: Building a foundation for a low-maintenance garden

Building a solid foundation starts with your garden’s soil and there’s no better way to build a high-quality soil than to use mulch. Cedar mulch forms the foundation of our low-maintenance woodland garden. It’s benefits are too numerous to list but here’s a start.

A temporary alternative to natural ground cover

Good or bad, we all remember the gardens of our childhood.

I remember dry, barren earth that literally turned to sand when you held it in your hands. It was the 1960s and the only plants that grew in the front gardens were traditional purple iris.

Not that my parents didn’t try. They turned over the soil religiously revealing the darker damp soil for a few hours until the sun baked it again.

It’s hard to imagine a worse recipe for building high-quality, healthy soil. But they toiled on, sometimes adding peat moss or top soil. The ending was always the same. Dry, bleached and baked sandy soil.

The missing ingredient was, of course, mulch. I am sure it was available at that time, but it certainly wasn’t piled up in bags at every building supply, grocery and nursery store.

Today, cedar mulch is so common in our area, it’s hard to believe there are any cedar trees still standing.

Organic mulch is commonly made from bark or wood chippings, but it can also be made of grass clippings or pine needles (a popular choice in parts of the United States,) to name just a few.

Non-organic mulch is another option and another blog post but includes stone such as pea gravel, aggregates and man-made substances.

Cedar mulch is a forest byproduct made from the shredded wood of cedar trees. Compared to pine mulch, the inherent nature of cedar makes it a longer-lasting mulch in the garden.

The benefits of mulch far outweigh any argument for not using it. Not only is cedar mulch attractive, whether you choose natural-, black-, brown- or red-coloured, it has a pleasant smell for the first few weeks it is put down, helps unify the garden and better shows off the plant foliage.

Despite its obvious benefits, it’s still not unusual to see uncovered, baked earth on my daily walks, usually accompanied by the homeowners on their hands and knees pulling weeds or, God forbid, turning the soil over so they can enjoy a few hours of dark soil before the sun comes out to bake it beige again.

Mulch is the perfect backdrop for the foliage of this Pagoda dogwood, while it protects and insulates the soil below. Over time it breaks down and adds a woodsy organic material to the soil.

In many ways, mulch actually takes the place of a living ground cover.

And, although bark mulch is a great beginning to amending your soil an creating a more woodsy soild, it’s best not to consider it the finished product.

In a woodland garden, a native and natural ground cover such as wild geraniums, bunchberry or ferns are a more desirable alternative than organic mulch, but there are plenty of situations where a ground cover is not feasible at the time.

That’s where an organic mulch truly shines.

Without going into all the benefits of heavily mulching your gardens, let’s examine just a few of the reasons mulch should be high on your list when you are building your Woodland garden.

Water retention: By shading the soil with a thick layer of mulch (ideally 3 inches or more), evaporation, both from the sun and wind, is minimized.

It also helps to regulate the temperature of the soil further reducing water evaporation and giving the plants a layer of insulation that helps keep the plants’ roots cool in the summer and warm in winter.

It is important to note, however, that mulch can also act as a barrier that makes getting sufficient water to your plants’ roots more difficult. It is much more water-efficient to target the plants individually either through a drip system or by hand watering them individually.

Deep watering a plant by leaving the hose dripping at its roots for several hours will allow the water to dive deep into the ground rather than getting locked into the mulch layer or just licking the top inch of the soil.

If your garden is properly mulched, you need to water less often but when you do water, ensure you are deep watering and targeting the plants’ roots.

One of the often overlooked benefits of mulch is that it helps prevent water runoff by trapping the moisture and moving it slowly to the soil below.

During a major storm, for example, water that might traditionally just run off in one direction, flooding one area and leaving another area more or less dry, will be better constrained to the general area it fell on. The result, a more evenly irrigated garden that will retain the moisture much longer than barren earth – possibly days or even weeks.

Weed Inhibition: Everyone is striving for a low-maintenance garden. Mulch is the key ingredient to achieving that end. But, let’s not kid ourselves it can’t perform miracles, especially if it is spread too thinly over the soil.

We’ve all seen it. A layer of mulch so thin that you can see the soil through it. Using large pieces of bark rather than the shredded bark, is often the biggest culprit here.

Unlike the shredded mulch, or pine needles, the bark pieces are too large to properly cover the soil and the resulting gaps make it too easy for seeds to find their way to the soil. (If you really love the look of the larger bark pieces, consider using the shredded mulch as your primary covering and top dress with the larger pieces.)

if the ground is not covered properly, once the weed seeds germinate, pulling them out brings more soil to the surface and before you know it, your garden is covered in weeds.

The key is to block light from reaching the soil to keep the seeds from germinating.

Some seeds will germinate right in the mulch but without proper soil they are either not long-lived or easily removed because it is near impossible for them to get properly rooted in the bark medium.

Also, if you water your individual plants rather than a general watering of the entire garden, the weeds’ roots often eventually are starved of water and die off. This is especially true following a wet spring. Weeds from the previous year will sprout in the damp mulch left by snow cover, but as the mulch dries out, the seedling roots will often die off.

A common complaint against the use of cedar mulch in the garden is that it can deplete the amount of nitrogen in the soil. While this can be true, it is not something most homeowners should be worried about.

What is more worrying is the practise of piling mulch around trees and plants in a volcanic mound that is almost guaranteed to kill the plant over time.

I often see it done by unknowing city workers who like to pile mulch up the tree’s trunk as high as possible thinking they are conserving water. Do not fall into this trap. Roots of trees and plants do not benefit from mulch touching them in any way.

Keep the mulch away from the plants and, instead, create a bowl of mulch around the tree trunks or plants where the sides can hold the water or at least slow its runoff from around the plant or tree. The bowl should be larger according to the size of the tree or plant and can actually extend out to the drip line of a young tree or plant.

Paperbark Maple: Understory tree with year-round interest

The paperbark maple (acer griseum) is a mid-size understory that fits both small gardens as well as larger woodland-style gardens.

Paperbark Maple ideal for late fall colour in small urban yards

Paperbark Maples are as useful in the winter landscape with their exquisite, peeling cinnamon-coloured bark, as they are in summer when they perform as a beautiful, mid-size understory tree.

But don’t underestimate the Paperbark Maple’s outstanding performance in late fall when they light up the landscape long after most of the other deciduous trees are left naked.

Where to plant the Paperbark Maple for best results

Be sure to plant Paperbark Maple (acer griseum) in an area of your garden where you can appreciate it in every season.

Our Paperbark Maple is just steps away from our patio where we spend most of our time. It takes centre stage in late fall when its leaves just begin turning colour long after all the other deciduous trees have dropped their colourful leaves.

The Paperbark Maple is a lovely oval to rounded small tree with an open habit and upright branching. In fall, the dainty, three-lobed soft-green maple leaves turn a rich, rusty red.

How long does it take to reach maturity?

Acer griseum are a slow growing tree that will eventually reach about 25 ft. tall and between 15-20 ft. wide.

But unless you are buying a mature specimen, don’t expect the tree to reach those heights any time soon. Paperbark maples grow 6 to 12 inches a year depending on growing conditions.

Exfoliating papery bark is the show stopper year round

While the tree’s fall colour is often overlooked, the tree’s exfoliating papery sheets of bark that peel to reveal cinnamon-brown new bark is rarely overlooked in the landscape. It’s the bark, not unlike that of the river or white birch trees that makes acer griseum a special tree in a landscape.

How long before the bark on a paperbark maple begins to peel off?

If you have planted a young tree, don’t be surprised if you do not see any exfoliating bark for a few years. This can take up to seven years and is more evident on mature trees.

Do paperbark maples have pest problems?

Remarkably free of serious pest problems, the trees tolerate a wide range of conditions from sun to shade and wind.

They can also be attractive as a place to nest for birds, but are not known to be particularly effective in attracting either birds or other wildlife. The trees put out small yellow flowers in spring which can attract pollinators followed by two winged seeds about 1 cm long with a 3 cm wing, which can be a food source for backyard wildlife.

How to grow and use Paperbark Maples in the landscape

They like to grow in soil that is kept consistently moist, but not soggy, and are best grown in zones 5-8 in filtered sun, full sun or partial shade.

They are effective as an understory tree in a woodland or shade garden but because they like some sun, paperbark maples can be used as a specimen tree in a more open garden.

The compound leaves have a 2-4 cm petiole with three 3-10 cm long dark green leaflets.

What companion plants look good with Paperbark maples?

Good companion plants are various sedges, hostas and, of course a range of native spring wildflowers from trilliums, bloodroot and anemones, to bluebells. Keep the plants around the base of the tree on the shorter side so you can appreciate the full effect of the peeling bark.

These deciduous trees are at home in foundation beds in both front or back yards as an accent plant to greet visitors with its impressive bark. They can also work well in more wild, woodland settings, and in wetland conditions as transitions between the more formal garden and open spaces.

These trees are not native to North America. The Acer griseum originates from central China and was introduced to the U.K. in 1901. It came to North America a few years later. Cultivars include the columnar Copper Rocket.

What are good alternatives for the paperbark maple?

While the paperbark maple is an impressive, four-season tree that is at home in both the shade garden as an understory tree or as a specimen in a more sunny location, it may not be the best choice if you are looking for more native and wildlife-friendly trees in your landscape.

Other options to consider over the paperbark maples are, of course our native dogwoods ranging from the pagoda dogwood (cornus alternifolia), flowering dogwood (cornus florida), Redbud (cercis canadensis), Paw Paw (Asimina triloba) and the serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis).

Our native serviceberry is an excellent choice maintaining similar growth habits, beautiful white flowers in spring followed by red berries in fall that are a favourite food source for birds and other wildlife. It’s fall colours (oranges and reds) are also similar to the paperbark maple.

Purple pearl-like berries make Beautyberry a showstopper in native gardens

The American Beautyberry is a fall standout in the woodland garden with it pearl-like magenta berries. The native plant attracts bees and butterflies with its late summer bloom of delicate pink and white flowers, followed by spectacular late summer fruit that persists through winter.

The bright berries that look more like clusters of elegant purple pearls are the prize at the end of summer that makes the American beautyberry bush a must for native gardeners.

The fact that these stunning, glossy, iridescent-magenta fruit, which hug the branches at leaf axils throughout fall and winter, are favourite food sources for migrating birds makes these shrubs among the most prized of plants for gardeners looking for a native plant that turns the sad end of summer into a celebration.

This bumblebee became covered in pollen after working the beautyberry flowers. The flowers will eventually turn into the beautful pearl-like purple berries.

Beautyberries attract bees and butterflies

In mid summer, when the flowers are in bloom, the shrubs also attract native bees and butterflies.

What more can a native gardener ask for?

How about an attractive, arching shrub at home in a woodland understory or at the edge of a forest where it gets full sun to part sun,

Where can you grow Beautyberries?

American beautyberries (Callicarpa americana) are found in warmer parts of Canada and throughout the United States from Virginia to Arkansas and south to Florida and into Texas. They are generally hardy from Zones 6-1.

If you are looking for it growing naturally, look in woodlands, moist thickets and other wet areas including low rich bottomlands, swamp edges and pine woods.

If you are looking for more information on growing native flowers, you might be interested in going to my comprehensive article: Why we should use native plants in our gardens.

Other shrubs known for their berry production include a long list of viburnums. If you are looking to add more berry producers to your garden, check out my comprehensive post on Seven Viburnums that attract birds to your garden. In addition to Viburnums there are many plants, shrubs and small trees to consider. My post Best plants and shrubs to feed birds naturally and save money will help get you thinking about using plants and shrubs as natural bird feeders.

Are Beautyberries low maintenance?

If you are growing Beautyberry in your garden, you’ll be happy to know it is a low-maintenance shrub that is happy enough in moderately moist soil in part shade. Beautyberries grow in moist, rich soils as well as sandy soils, sandy loam and even clay-based soil.

Beautyberries boast spectacular, magenta fruit born in clusters on arching branches that can remain on the shrub into winter.

Is my Beautyberry dead?

Don’t be surprised in late spring if there is no sign of life in your Beautyberry. These shrubs are slow to bud out in the spring, but the American beautyberry can reach an average of 3-5 feet tall and often about the same width. In good soil, don’t be surprised if it reaches up to 9 feet high with a similar width. it can be cut down regularly to keep it in check if necessary.

During the summer, the shrub with its arching branches and ovate to elliptic, leaves. that grow in pairs or in threes up to nine inches long, are fairly inconspicuous blending in with other shrubs in the garden border or filling in under larger mid-canopy trees.

If used as a specimen, it can be an elegant understory shrub with a naturally loose and graceful arching form.

Plant it as a mid-size understory shrub at the edge of the landscape where it can get partial sunlight during the day, preferably in morning or late afternoon.

In late summer – mid august in our area – small, pink flowers appear in dense clusters at the base of the leaves. These delicate clusters of flowers are easily overlooked.

Gardeners familiar with the shrub know however, that the more flowers they have on their beautyberries the more berries they can look forward to in late summer into fall.

Flower buds on a Beautyberry bush getting set to emerge and eventually turn into the purple pearl-like fruit that is attractive to a variety of birds including robins, cardinals and mockingbirds.

The fruit or berries can be rose pink or lavender pink and about 1/4 inch long. The extremely showy clusters cling to the branches through the fall and into winter if the birds and garden mammals don’t get to them first.

Do Beautyberries have good fall colour?

Fall is really the time the shrub comes into its own as the leaves slowly turn yellow revealing the incredibly showy clusters of glossy fruit. The combination of the yellow leaves and magenta fruit is a combination that you will want to ensure is front and centre in the garden.

What birds eat the fruit of Beautyberry?

You can count on American robins, cardinals, finches, towhees and even mockingbirds visiting your shrub in search of the pearlescent, purple fruit. Foxes, raccoons, chipmunks and squirrels will also be lining up for the fruit.

Unfortunately, if you live in deer country, don’t be surprised if deer have a little nibble on the shrubs. Our deer have more or less left the plants alone, although there is so much more in the garden they obviously seem to prefer.

Although American Beautyberry shrubs are commercially available, (you may have to look for Callicarpa americana on the tag ) they are relatively easy to propagate from seeds, root cuttings and softwood tip cuttings. If you have a friend with one, take a cutting and get a couple for your garden.

Sophisticated elegance makes Beautyberry a late summer standout

The American Beautyberry shrub is another example of a native plant that is often overlooked by gardeners focusing on massive, showy blooms that dominate the landscape but often fall short once the blooms are spent.

This is not what the Beautyberry is all about. Although these understory shrubs have a certain elegance in the woodland garden with their arching stems, don’t expect them to steal the show during the spring and summer months.

But that’s okay.

There are plenty of flowers, shrubs and flowering trees that can do the heavy lifting in May and June. Gardens need colour and interest in late summer into fall and that’s when the American Beautyberry really delivers. As already discussed, the berries/fruit are the showstoppers, but don’t underestimate the fall foliage. The green and almost lemon-yellow foliage of the Beauty-berry is the perfect contrast to all the reds and burnt orange that tends to dominate the landscape at this time of year.

Not only do Beautyberry carry their weight in fall, but they add much needed winter interest to the landscape with their purple berries popping out of the drab landscape. Imagine watching a cardinal feeding on the colourful fruit and you will know why native woodland gardeners have a special place in their hearts for Callicarpa americana.

How long before Paperbark Birch trunks turn white?

Birch trees are among the most used trees in our landscapes because of their showy white bark that is a real standout in all seasons. How long does it take before the bark turns white? A typically-sized tree purchased at a local nursery can take between 3-5 years before it turns white. A more mature tree would take less time and a very young tree would take up to ten years to turn white.

One of the prettiest trees in our landscapes are undoubtedly White Birch. Their incredible white bark lights up the landscape throughout the seasons, especially if the trunks are uplighted at night to draw even more attention to their glowing white trunks.

But how long does it take the trunks of a typical Paper Bark White Birch tree Betula papyrifera to turn from the cinnamon brown colour present in immature trees into the outstanding white papery bark we are all so familiar with in the landscape?

The answer to that question may vary to some degree depending on the age of the tree purchased from the nursery, the location the tree is planted and the amount of water and, to a lesser degree, the soil conditions where it is growing.

In a typical, store-bought clump or single-stem White Birch tree that is small enough to carry home in the back of your hatchback wagon or truck, you can expect at least a 3- to 4-year wait before the trunks begin to turn white. If you purchase a more mature tree that is already beginning to show signs of whitish-orange bark, expect a year or maybe two before the reddish-brown bark with its horizontal slits (lenticels) gives way to a reddish orange bark and eventually is peeled off enough to reveal the white paper bark.

Very immature trees that are purchased as “whips” may take up to ten years before you are blessed with solid white birch bark.

The white birch bark of this clump shows how far along the three main trunks are in comparison to the much younger fourth trunk still in its reddish-brown phase. This fourth trunk is probably 2-3 years away from taking on its all-white trunk. The solar-powered uplighting on the white trunks creates a real mood in the evenings.

How quickly do Birch trees grow?

Birch trees are considered relatively fast growers where they are happy. On a good year, expect anywhere from 13 inches to more than 24 inches (or two feet) a year for your average White Birch tree or clump. The paper birch grows to a height of between 50’-70’ with a spread of around 35’ when mature. The River Birch enjoys a similar growth habit.

This image illustrates the peeling bark of another one of our clump birches that is just entering its pure white phase. The cinnamon bark on the left is just beginning to reveal the white bark. It’s noteworthy that this clump is just 9 or 10 feet from the clump shown above that is much further along in its transformation from reddish brown to white.

Should I plant a birch tree in my urban landscape?

The white birch is a medium-sized tree that is very common in urban landscapes despite its relatively short-lived existence under these more difficult conditions.

Birch trees are generally unable to handle excessive heat and humidity which are often exacerbated in urban landscapes where they are planted near asphalt driveways or close to homes where they are unable to get proper air flow to keep them cooler.

These urban trees and others living in zones 6 and up may live only about 30 years – even less if they are under extreme stress.

It’s a good idea to keep this in mind when planning a landscape in urban areas. Birch trees cannot be counted on to live long lives and may have to be removed leaving a large hole just when your landscape has matured nicely and is looking its best. On the other hand, if you have a very sunny area, say for example in a new subdivision, a fast-growing birch tree will bring relief from the hot sun and provide a beautiful specimen for years to come. A good idea might be to plant a small, slower-growing oak or maple tree nearby which will slowly take over once the birch tree begins to decline.

At some point, you could even cut down the birch tree to make room for the larger, more long-lived native oak or maple.

In the wild, or in a more rural location or woodland-type garden, the white birch is often able to survive longer and grow to heights of between 50 and 70 feet. A typical trunk measures about 1 to 2 feet wide. Trees in colder climates, however, can even live for more than 100 years.

The leaves of the white birch are ovate and the catkins (male and female flowers) can grow up to 4 inches long. The female catkins form cylindrical cones that disintegrate when ripe, spreading the seeds which are eaten by many birds and small mammals including chickadees, redpolls, voles and ruffed grouse.

By uplighting the Birch clumps, you can appreciate their white trunks both day and night.

For more on Birch Trees in the Woodland garden check out my other articles:

On our property, we have two areas with birch trees: a grouping of three narrow weeping purple birch in the front that were purchased as very young whips, and three clump birches planted in the back yard that together have at least ten main trunks combined.

Our final clump of birch trees planted at the same time as the other two clumps, is significantly behind the other clumps in growth and maturity despite being purchased and planted at the same time. This clump, although already in the ground for four years, is still a year or two away from obtaining their white trunks.

The three young whips (Betula pendula ‘Purpurea’ )planted in the front took several years to begin displaying their white trunks. After maybe ten years of growth they have matured into a lovely grouping of weeping birch trees. These trees are slow-growing and upright as young trees, that eventually begin to weep more with age, and sport bronze-purple leaves and silver-grey bark.

The clump birches in the backyard are further along after only about 3-4 years in the ground. To give you an idea about the original size of the clumps, they were all purchased from a big-box store and taken home in the back of our Subaru Outback wagon. Although the containers were quite large, I was able to get all three into the back of the wagon to transport them home. (This helps to give readers an idea of the trees’ original size.)

Our three clump birches in the back were all planted at the same time and within about six feet to 10 feet of one another to create a small birch grove. They are, however, taking on their magnificent white trunks at significantly different rates. This tells me that the amount of sun, water and quality of soil they receive have obviously also played a role in how quickly the trees take on their papery-white trunks.

Birch trees are early colonizers after a fire or natural disaster so they prefer to grow in open sunny areas and will not do well in shade. Our clump that is the slowest to mature is also the clump that gets the least amount of sun. The other two clumps block much of the sun from the third clump.

The trees also require plenty of water, so mulching around the tree roots to retain moisture is a good idea.

Recent hot, dry spells have stressed our birch trees in the backyard to the point where their leaves are beginning to turn yellow and dropping off a little earlier than I would like. Deep watering is required, especially prior to winter to keep the trees hydrated.

(Go here, for my article explaining early leaf drop of birch trees.)

A male cardinal hanging out in a birch tree just beginning to get its white bark.

Why is the bark white?

Studies have shown that the white bark of birch trees serves it well when it comes to regulating the tree’s internal temperature, especially in the more northern climates where the trees tend to live much longer.

The white bark is known to reflect the sun’s heat away from the tree during cold spells, which helps to protect the tree’s vital cambium layer just beneath the bark.

If the Birch’s bark were the more typical dark colour found in other trees, the life-giving liquid that travels up and down the tree’s trunk through the cambium layer would be constantly fluctuating between freezing and thawing, which would eventually weaken and kill the tree. The reflective qualities of the white birch bark helps to regulate the temperature and allow the trees to survive during extreme weather conditions.

This trait is likely to play an important role in the tree’s survival as climate change continues to play havoc with our more northern growing zones.

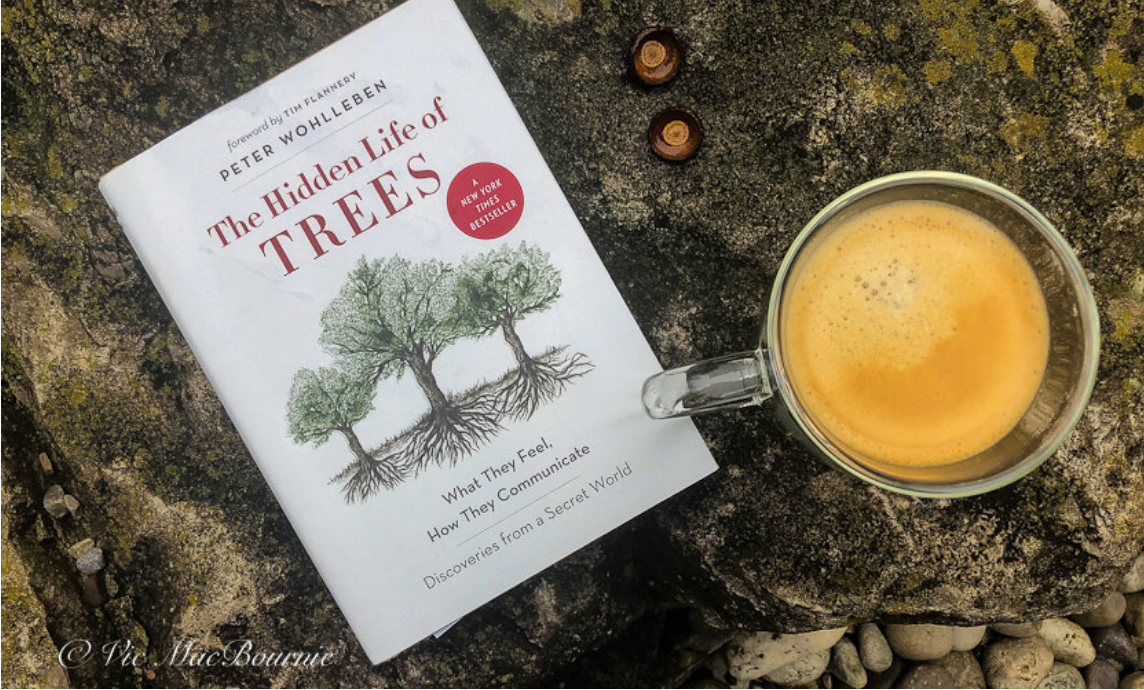

How trees communicate in our woodland gardens: The Hidden Life of Trees

The Hidden Life of Trees is a New York Times bestseller every Woodland Gardener needs to read. Author Peter Wohlleben explores how trees communicate in nature and how they struggle in urban environments calling them “street kids” and explaining the difficulties they face in our woodland gardens and on urban environments.

Do trees work together to help one another?

If you love trees – and I know every woodland gardener does – then you need to get The Hidden Life of TREES. (Amazon Link)

Peter Wohlleben’s 288-page, New York Times best seller will open up a new world for Woodland gardeners looking for answers about what is really going on in their backyards, local woodlots and ancient forests.

There is a reason this book has sold more than 2 million copies. Canadian publisher Greystone Books unleashed the book in its 8th printing on September, 2016 in the First English Language Edition, and has never looked back. (A fully illustrated coffee-table version is also available, see below.)

Not convinced about the importance of this book, consider that it has also been made into a movie. Check out this YouTube link for a taste of The Hidden Life of Trees movie version. (It will be available on AppleTV starting the month of October.)

It should come as no surprise to any of us that several backyard trees work together to create their own environment – from cooling our yards with shade to creating their own fertilization and micro environments at ground level.

Sit back and relax with a good coffee and The Hidden Life of Trees. The New York Times best seller is a must for Woodland gardeners.

What will come as a surprise to most of us, however, is the incredible goings on under our feet – from just a few inches beneath the soil to the depths many of our mighty tree roots reach. Beneath the soil there’s a communication highway where battles are waged, where life and death struggles play out through the seasons, and where families of trees come together through the “Mother Tree” and work together, sometimes over centuries, to survive, and ensure the health and prosperity of the woodland.

If you are looking to purchase the Hidden Life of Trees, or any other gardening book for that matter, be sure to check out the outstanding selection and prices at alibris books.

Armed with this knowledge, woodland gardeners can begin to make sense of so many questions about our gardens; its forest canopies, why a variety of tree is not flourishing and how we can help our woodland thrive.

(Dr. Nadina Galle has taken her inspiration from The Hidden Life of Trees and The Heartbeat of Trees and used it as a building block in her groundbreaking work to use smart technology to monitor the health of the urban forest. Read about her outstanding work here in my recent article The Internet of Nature.)

But this is not a how-to book. There are no pictures of trees. There are no outright tips for how to plant trees, where to plant them or when to plant them.

The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate is a book that explores the often mysterious lives of individual trees, of forests, of trees left alone to fend for themselves in urban areas, on our streets and in our backyards. This is a book, written by a German forester, about how trees have communicated with one another over decades and even centuries, how they work together to save their own against disease, natural disasters, man’s destructive habits and the invaders we have brought that threaten the very existence of our native trees. Underlying it all, is the affect climate change is having and will continue to have on our woodlands, our urban forests and ancient rainforests.

“Life as a forester became exciting once again. Every day in the forest was a day of discovery. This led me to unusual ways of managing the forest. When you know that trees experience pain and have memories and that tree parents live together with their children, then you can no longer just chop them down and disrupt their lives with large machines.”

Trees work

Will a single tree thrive in my yard?

The author makes it clear from the beginning that the lone tree in the middle of our front and back yards surrounded by grass that is so prevalent in many urban homes, is not an ideal situation for a tree’s prosperity.

“A tree is not a forest. On its own, a tree cannot establish a consistent local climate. It is at the mercy of wind and weather. But together, many trees create an ecosystem that moderates extremes of heat and cold, stores a great deal of water, and generates a great deal of humidity. And in this protected environment, trees can live to be very old. To get to this point, the community must remain intact no matter what. If every tree was looking out for only itself, then quite of few of them would never reach old age.”

The above quote may well explain why our urban trees rarely reach maturity, let alone old age. Where I live, this is clearly evident in local birch trees. In the heart or our urban communities these trees rarely survive into maturity. In the older, more rural areas where trees are less crowded and are given more room to grow, Birch trees seem to do much better. In my yard, I have planted three clumps quite close to one another and they seem extremely happy, possibly beginning to communicate with one another.

As trees struggle on their own, some would die opening up the forest floor to sunlight, the author explains. “The heat of summer would reach the forest floor and dry it out. Every tree would suffer.”

Do trees help one another survive?

If we conclude that every tree is valuable to the forest community and worth keeping around, it should come as no surprise that, as Wohlleben writes, “…even sick individuals are supported and nourished until they recover.”

He compares them to a herd of elephants. “like the herd, they, too look after their own, and they help their sick and weak back up onto their feet. They are even reluctant to abandon their own.”

If you have never thought about trees in this way, you may be shocked about how deep Wohlleben goes to explain just how extensively trees communicate through primarily – but not limited to – underground networks.

For the doubters, let me just say that his arguments and scientific data are hard to ignore.

Five key takeaways from this book

• Trees are much more complicated than most of us realize and their means of communication are complex and sophisticated.

• The importance of planting a grouping (possibly an island or a grove if possible) of the same variety of native trees is much more beneficial than planting individual specimens, especially if they are non-native trees.

• Recognizing that a tree’s needs must be met not just after initial planting but long into their growth cycle is important, and reducing physical barriers can be critically important.

• Single trees planted in our yards are more on their own than we might realize, and it matters that they cannot communicate easily with other trees. Best to take extra care of these lone trees.

• A woodland garden thrives not only because it is more natural than say a cottage garden, but because trees work together to create a positive environment that helps to guarantee success even when they are threatened.

Can trees communicate?

Consider that four decades ago, scientists noticed an interesting phenomenon on the African savannah.

They noted that giraffes feeding on acacia trees moved on quickly to other trees. The same scientists discovered that mere minutes after the giraffes began feeding on the trees, the acacias began pumping toxic substances into their leaves to ward off the large herbivores. The giraffes moved on, walked past a number of nearby acacias, before resuming their feeding on a group of trees about 100 yards away.

“The reason for this behavior is astonishing. The acacia trees that were being eaten gave off a warning gas that signaled to neighbouring trees of the same species that a crisis was at hand. Right away, all the forewarned trees also pumped toxins into their leaves to prepare themselves…. The giraffes were wise to this game and therefore moved farther away … to a part of the savannah where they could find trees that were oblivious to what was going on.”

The entire book is filled with fascinating stories about how trees’ self defences are used to ward off fungal diseases, beetle attacks and even how they deal with woodpeckers and other potentially destructive mammals that depend on trees for their own survival.

This is just an example of the many ways trees may communicate in a natural environment. The book goes on to explain a myriad of ways trees communicate, but in doing so, it also explores the many ways communication between trees is cut off leaving orphaned trees alone and fending for themselves.

Communication between trees growing in managed forests and in many of our urban parks is often restricted and underdeveloped for a variety of reasons explored in the book.

How are single trees like “street kids”?

But it’s the chapters on street kids that many gardeners and homeowners will likely focus on the most.

A drive down a suburban street or through a large city reveals just how many trees are left alone to fend for themselves.

In his book, Wohlleben describes these orphaned trees as “street kids.”

“Urban trees are the street kids of the forest. And some are growing in locations that make the name an even better fit – right on the street. The first few decades of their lives are similar to their colleagues in the park. They are pampered and primped. Sometimes they even have their own personal irrigation lines and customized watering schedules.”

The problem comes when these trees decide it’s time to go out and establish themselves. They quickly meet with hard, unlivable soil and even concrete walkways, roads that don’t allow any water to penetrate down into the hard soil compacted by machinery

“When trees are planted in these restrictive spaces, conflicts are inevitable….The culprit is sentenced to death.”

It is cut down and another planted in its place, but the new one is planted in a built-in root cage to restrict its roots from ever causing damage to the surrounding hardscaping.

Sound familiar?

What problems does a single tree face?

The difficulties “street kids” face does not end there. In large urban areas, where the lights never go out, these trees never get a chance to rest. They need a period of rest to thrive. Often, the concrete traps heat and even winters, another time for the tree to rest, are non-existant.

The sun, too, heats the concrete and black asphalt to the point of killing any living organism in the soil beneath it, depriving the “street kids” of water and nourishment.

In large urban areas these problems are obvious, but take a look around at your own trees and consider if they are facing some of these same problems.

Are the roots of the tree in your front yard growing under the road? Would additional watering help it survive hot, dry periods?

Is your favourite dogwood struggling because it is now in bright sunlight most of the day after a neighbour cut down a large maple exposing it to harsh sunlight? Maybe we need to add a large shade tree nearby to reduce the amount of sunlight hitting the dogwood.

Is your concrete driveway cutting off all water to your favourite roadside maple tree? Maybe it’s time to do what I did and replace the old asphalt or concrete with stone or permeable brick to allow water to seep down into the roots of the tree. Not only will it help the tree, it also reduced the amount of toxic runoff from your driveway into the sewer systems by keeping more water on your property.

As I said earlier: this is not a how-to book, but it certainly provides food for thought about how we can help our own little forest survive and thrive in our woodland garden.

About the Author: Peter Wohlleben spent over twenty years working for the forestry commission in Germany before leaving to put his ideas of ecology into practice. He now runs an environmentally-friendly woodland in Germany, where he is working for the return of primeval forests. He is the author of numerous books about the natural world including The Hidden Life of Trees, The Inner Lives of Animals, and The Secret Wisdom of Nature, which together make up his bestselling The Mysteries of Nature Series. He has also written numerous books for children including Can You Hear the Trees Talking? and Peter and the Tree Children.

If you like the Hidden Life of Trees, be sure to check out its sequel The Heartbeat of Trees recently published.

Green Giant cedars: Fast growing arborvitae ideal for privacy

Go big or go home so the saying goes. I think it might better read, Bring Big home in the form of Green Giant cedars. If you are looking for a fast-growing privacy hedge or an elegant evergreen to make a statement in your woodland garden, the Green Giant might be the answer.

Green Giant arborvitae create year-round privacy fast

Is there room anymore in our gardens for big? Big trees, big shrubs, big boulders – BIG, Bold colour and plantings.

Well, make room for the Green Giant. Thuya Green Giant, Green Giant Arborvitae, call it what you wish. These are big, bold evergreens in your garden and we all need more of these type of statements in our woodland gardens.

Want privacy? This is how you get it. And not just in the summer. Green Giants provide year-round privacy and they do it quickly. There is no need to wait years to eliminate that eyesore or bothersome neighbour.

It seems like everything is miniaturized in garden centres these days, aimed more at timid gardeners who have been convinced that their properties are too small to handle any larger-sized trees, plants and shrubs.

Well, Green Giants are here to prove that big and bold is beautiful. If there was a bean stock, Thuya Green Giant would outgrow it and look fantastic doing it.

Let’s take a closer look at these evergreens – also known as Green Giant Arborvitae – that grow big fast, provide the perfect evergreen screen when you need it in a hurry, have a beautiful dense deep green colour and a natural loose habit that allows them to fit into a natural woodland setting. They are shelter for wildlife during our cold winters, a nesting spot for birds in spring and summer and best of all, deer leave them alone. That’s not all, Green Giants are not bothered by insects or disease and can stand up to most adverse weather situations.

A cedar deer don’t like

Yes, you read that right. A cedar that deer, including those all around our property, will not devour in a day.

Thuja Green Giants (Thuja Standishii Plicata ‘Green Giant’) did not earn their names from being timid.

These things can grow to enormous heights (40-60 ft) with a width of between 12-20 ft. And they don’t waste time doing it putting on 3 to 5 feet of growth a season when they’re happy.

These pyramidal shaped cedars grow in zones 5-7 and are an excellent disease-free substitute for other plants like Western Red Cedar or Leyland Cypress. Spring growth emerges a fresh lighter green and winter colour is a darker, bronzer shade.

These Green Giants form the perfect natural privacy screen between our neighbours and us, creating a wall of soft evergreen that even the birds enjoy.

They can grow happily in full sun to partial shade, in acidic or alkaline soil and are not fussy about whether it’s sandy or heavy clay.

So, in other words, these things will grow just about anywhere, in any soil conditions.

Use them as a specimen tree and let them be free to grow into their natural shape in your yard, or plant them together every 5 to 6 feet to create a privacy barrier to your property from neighbours, unsightly objects and busy streets. Their dense foliage will go a long way to not only block out the view but reduce noise and act as a possible wind-break.

Your choice to grow as a specimen or a privacy screen, but I always lean to allowing a tree to grow into its natural shape.

Green Giants on our property

In fact, the pictures above show the 8 Green Giants my neighbour and I planted between our properties last summer.

The results are impressive.

We chose the Green Giants to replace an unsightly, overgrown deciduous hedge that had long past its prime. They were planted close together (about 6 feet) and staggered them to give the foliage more room to grow and spread out.

The result is stunning. The growth rate is spectacular.

The original 5-foot cedars grew two to three feet the first year we planted them and they are already forming a solid screen between us.

I’m hoping we can grow them more as large specimens with minimum pruning but time will dictate that. If they get too big width-wise, we could always remove a couple to give them more room to grow naturally.

This spring, I have noticed that the birds have discovered it and I think are beginning to take up residence in their lovely dense foliage.

Of particular note to those looking to save some money. Two of the eight trees we planted were much smaller than the other six trees. The nursery ran out of the larger trees, so we purchased two of the smaller, less expensive cedars.

Buy small and save big on Green Giants

As an experiment, we put them up front where they will receive more direct evening sun than the larger specimens. We expected the smaller ones to perform better than the larger specimens and eventually catch up to the point where it would be hard to recognize any real difference between them.

We were shocked to see the smaller cedars almost catch up to their larger neighbours in one season of growth. I imagine that by the end of the second year, it will be hard to distinguish between the smaller cedars and the larger ones.

So, if you are looking to save money as well as make the planting procedure much easier with the smaller root balls, consider going with the smaller versions of the cedars at the nursery. The growth rate is so strong on these trees that you will not have to wait long before they begin filling in and meeting your goals.

Emerald cedars vs Green Giants

I am going to go out on a limb here and just say it – why are so many gardeners choosing Emerald Green cedars (Thuja occidentalis ‘Smaragd’) over Green Giants or other, more natural looking, cedars?

I believe it all goes back to what the nurseries are offering and the push toward a smaller-scaled landscape because (in my mind) it certainly is not because Emerald Green cedars are nice.

They may look nice on the nursery lot with their bright green foliage but, to my eye, they don’t look appropriate in most landscapes. Hardy to zone 3b and growing to a height of only 12 feet with a spread of only about 4 feet, I can see why homeowners are originally attracted to these trees.

But the narrowness and upright, extremely dense foliage and brighter green colour just gives these a far too stiff and formal look to my liking. They work fine in a more formal setting, but I really don’t think they belong in a more natural setting and certainly not in a woodland garden.

My biggest problem with them is that, because the growth is so tight, the branches don’t intermingle well together and when they do, they often die off because of a lack of sun. The result, if any pruning is done to them, are ugly brown dead areas.

Is it obvious that I don’t like them much?

Just to add to my dislike, these things don’t live long at all averaging only about 30 years.

Consider the Black cedar or white cedars if deer are not an issue

My first choice in cedars is by far Black cedars (Thuja occidentalis ‘Nigra’). These are very much like Green Giants but are described as a selection of a native North American species. The Black cedars’ natural foliage that is a dense, dark and green with a little bit of a dusty-green look is even nicer than the Green Giants’ also impressive foliage.

A friend of mine recently put in a row of the black cedars along a fence and the result is stunning.

Black cedars grow fast to about 20 feet with a 7 foot spread, but not as quickly as Green Giants. The Nigra takes a pruning well and likes at least some sun over the course of the day.

The only reason my neighbour and I chose Green Giants over Black cedars is the fact that deer would have devastated the Black cedars within a week of planting them.

Following black cedars, our native swamp cedars, (Thuja Occidentalis) commonly known as the Arbor Vitae, Arborvitae, Eastern Arborvitae, Eastern White-cedar, Northern White Cedar, Northern White-cedar, Swamp-cedar, would be my next choice. These are often sold at the nurseries in spring as bare rooted cedars. They look spindly and not very attractive upon purchase, but are very cheap, grow fast and eventually thicken up to create an almost impenetrable privacy wall or impressive specimens. Under the right conditions, these are also very long lived.

These white cedars are perfect, accept they are high on the list of favourite food for our local deer population.

Again, Green Giants are of no interest to deer. My neighbour and I went through an entire winter where the deer left our Green Giants alone, and we did not even spray them with any deer repellent.

Impressive to say the least.

Why don’t I like Emerald Green cedars. They grow too tightly, too slowly and don’t provide the privacy that Green Giants or other more ‘loose-growing cedars’ can provide homeowners. In addition, their bright green foliage stands out in the landscape too much, in my mind. Rather than forming a perfect dark background, the Emeralds want to take centre stage.

Their biggest problem, as I mentioned earlier, is that because of their tight growth habit, if they begin to grow together like we want them to so they provide privacy, they will die off where they touch because of a lack of sun. If enough space is left between them to allow for their mature growth, they fail to provide the wall of privacy that the homeowner originally bought them for.

I know that landscapers are using them a lot and nurseries are pushing them to homeowners as the perfect hedging material, but consider their drawbacks before you go ahead and plant them.

One of our neighbours has them along their driveway, and every year they have to wrap them in burlap to stop the deer from snacking on them as well as protect them from cold winds. That’s not something I’m interested in doing, but if you are okay with it, by all means plant them.

Many homeowners like Emerald cedars, I happen to not be one of them. I’m definitely biased, so if you like them, plant them.

Green Giants are far from perfect

This is not to say that Green Giants are the perfect tree.

Anything that grows as fast as Green Giants come with their own problems. Silver maples, poplars and birch trees are good examples of fast-growing trees that, although they have their benefits, also come with big problems.

The faster a tree grows, generally the weaker its wood.

Why does that matter?

It matters most in severe weather when heavy snows or high winds can snap branches off. Whether they hit your home or just leave the trees unsightly, it’s never a good thing to have branches breaking on your trees.

In the case of cedars, it’s not uncommon for the tree branches to split resulting in either complete destruction of the tree or severe disfiguring.

This winter we did have a severe late winter snowstorm that left our cedars bent over by the heavy snow. I went out with a broom to clear some of the snow knowing that the trees can suffer damage in these situations. Turned out that they bounced back immediately and came through the storm with flying colours.

Another problem with fast growing trees is that they tend not to have long lives. Green Giants are given about a 40-year life span. I’m sure that in the right conditions they can live much longer but on average that is what you can expect.

The sheer size of these fast-growing trees is obviously a problem for some people. If you are young, you might want to consider the full mature height of these trees. They get large and can take up a lot of room if they are allowed to grow naturally. That can be a good or bad thing depending on the size of your yard and how you plan to use the tree(s) in your landscape.

My neighbour and I are, let’s say well past being called ‘young’ so having a fast-growing tree is perfect for us.

Let’s just say we are not too worried about either outliving the trees or about them getting to big in our lifetime. Your situation might be different. If so, a different type of tree might be a better choice, but don’t immediately write off a fast growing tree like the Green Giants.

If you need a quick cover that looks great, it’s hard to beat the vigour and beauty of the Green Giant cedar.

As an affiliate marketer with Amazon or other marketing companies, I earn money from qualifying purchases.

Can I plant trees close to my house?

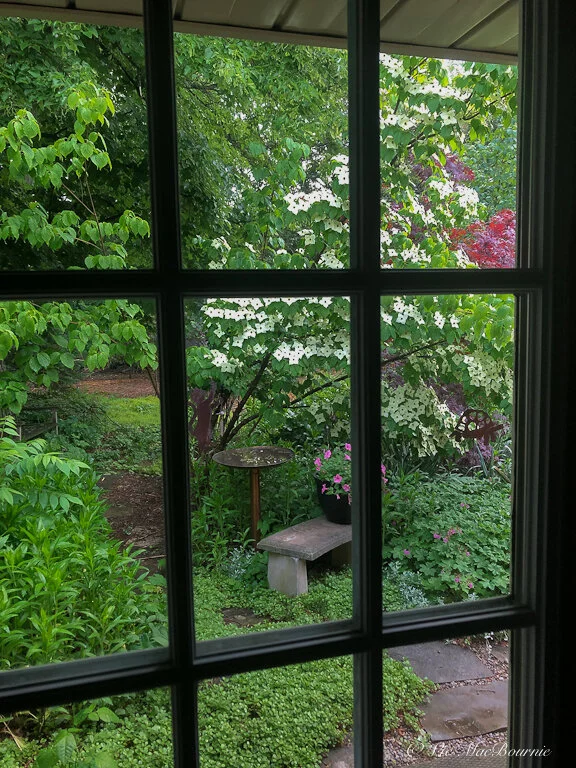

Creating a window into your low-maintenance Woodland Garden can be as simple as planting a tree or shrub up close to your favourite window to experience nature up close. Most gardeners have been happy to view their gardens from afar. Now is the time to consider landscaping our yards to bring our gardens indoors. Consider creating garden vignettes that incorporate a beautiful bird bath, a bird house or even better an elegant bird feeder, or water feature just outside your window for full-season interest and a window into your woodland.

Planting trees in close to your home and windows helps to give you a window into your woodland.

Trees planted close to windows create rooms with a view

You shouldn’t have to step outside to enjoy your Woodland and wildlife garden. By creating impressive views from inside your home, the garden and its wildlife always has a presence.

Whether it’s a full fledged Woodland that stretches out as far as the eye can see, or a smaller area in your garden, consider finding ways to welcome it into your home.

In winter, you’ll appreciate looking out at the birds flitting from branch to branch. In spring, you might be lucky enough to watch a pair of cardinals build a nest and raise their young.

There are plenty of ways to bring the outdoors in, but I find planting trees, shrubs, grasses, ground covers and flowers close to the windows in our one-storey house to be the best way to experience the woodland garden at all times.

Looking out and seeing birds in the branches just outside the window is such a pleasant experience compared to looking out over a sea of grass with gardens in the distance.

I also don’t worry about tree roots invading our basement. I am aware that this can and does occur at times – mostly in 100-plus year old homes with massive oak trees or maples planted very close to the home. By planting trees with less aggressive rooting systems, these problems can be averted.

A few good trees to plant near a home include birches, various forms of apple including crabapples, dogwoods, Japanese maples and hawthorn trees.

Trees to keep away from your home’s foundation include silver maple, poplars and white ash.

Our trees are far enough away that I am not concerned that they will ever get large enough to do any damage to the foundation of the home. Besides, I won’t probably be around by the time that occurs. In the meantime, I am going to enjoy feeling one with nature.

Getting up close and personal

There are many ways to get up close and personal with nature.

Some involve constructing outdoor structures … or building expensive three- and four-season rooms that reach into your garden and surround you with your woodland in a climate-controlled, mosquito-free environment.

Perfect, but often very pricey.

It’s a whole lot easier and much less expensive to simply take advantage of what’s already staring you in the face.

Existing windows and doors are an opportunity many gardeners overlook when it comes to maximizing their gardens. It’s not enough to simply look out over the garden, try to bring the woodland in close to give you an intimate window into the goings on in your garden. Birds flitting from branch to branch or a mother feeding her young just on the other side of the window provides all the entertainment you need over your morning coffee, breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Create vignettes outside your windows

Similar to indoor decorating, look to create vignettes on the outside that you can appreciate from inside.

French doors, for example, provide the perfect opportunity to create a beautiful vignette just outside the doors.

Outside our family room French door is a beautiful copper birdbath, a small concrete bench, a container full of annual flowers as well as a beautiful flowering Cornus Kousa. A small flagstone pathway gives the viewers’ eyes a view past a rose bush and into the main garden.

From the couch in the family room, I can watch a steady procession of birds at the birdbath and admire the beautiful view of the flowering dogwood. In winter the birdbath is heated to continue to provide entertainment while giving the birds vital fresh water and a bathing opportunity even in the dead of winter.

In your garden, it may be nothing more than a grouping of pots filled with colourful plants or dramatic grasses, garden art or a simple bird bath, or water feature that you can appreciate from both indoors and out.

Five ways to bring the Woodland inside:

• Spend time standing at or looking out the windows of your home in every season and dream of what you might want to view. Then make it happen

• Plant trees or clumps of trees close to your home outside windows and doors to give you intimate views of nature from inside your home.

• Plan a lovely vignette outside your favourite window.

• If you have a window overlooking a neighbour, consider planting cedars. Make sure they are either native white cedar, black cedar or a cultivar that is loose and natural feeling. Some of the cedars sold at nurseries are more ornamental and not really the best for hedging. The best cedars grow taller than a fence, provide year-round interest and attract birds both as nesting areas and food sources. Hang a small feeder nearby for even more entertainment.

• If you need new windows or doors, take advantage of the opportunity by either increasing the amount of glazing (glass) or using a French door or sliders over a standard door. Maximize your view and then create the view you dream of through landscaping.

Wise words from a professional landscaper

A landscape professional once told me that a good landscape allows people to live in it not just admire it from afar.

It’s an approach we all need to consider more carefully when we create our landscapes. Planting trees or shrubs close to windows and places where we spend the most time is a sure fire way to fully experience our gardens.

Natural tree canopies replace umbrellas

Why use a massive garden umbrella to give you shade from the afternoon sun, when a large tree canopy can do it with greater style? Plant that tree now and by the time it provides you with the canopy you desire, your existing umbrella will need replacing.

We are lucky enough to have large windows in both the front and back of our ranch-style home. In addition, to open the garden up even more, every exterior door has been converted to either have a large window or turned into a French door for maximum viewing.

To some extent, our gardens are designed around the windows.

Our large front picture windows look out onto a grassless woodland setting that includes, among other plants and trees, Japanese maples, a lovely serviceberry, fully mature Crimson and red maples as well as our neighbour’s large blue spruce trees.

But it’s our view out into the back garden that best illustrates our attempt to bring the Woodland indoors.

Creating a view: Designing a dry-river bed

After years of looking out a large dining room bay window into our back garden, it donned on me that we really needed to create an interesting view that we could appreciate year round.

The view had always begged for something special, but I could never decide how best to use the space.

Over the years, it primarily served as our main bird- and deer-feeding stations. The birds and deer provided plenty of entertainment, but it was time for a change.

Although it was completed just three years ago, it’s fair to say this project was years in the making.

It began with a plan to create a dry-river bed that connected to an existing pathway of river rock, pea gravel and flagstone stepping stones – a landscaping project my wife and I completed many years earlier. I liked the look and feel of the existing pathway and thought it would be good to bring that same feeling out into the landscape.

Since a bubbling rock has always been a dream of mine, we incorporated a small solar powered pump with a bubbling rock at the head of the dry-river bed. The idea was coming together in my mind but it needed more to make it look natural and bring it together as a cohesive landscape.

Eventually, after combing Pinterest for dry-river ideas, the concept of a bubbling rock and dry river bed running through a forest of birch trees was born.

Soon after, three clump birches were planted in the area around where the dry river bed would eventually go. The bubbling rock and dry river bed followed.

Grasses, ground covers and native flowers have been added since then to soften the hard edge of the river bed rocks and, three years later, the entire project is beginning to settle nicely into the landscape.

The birches seem happy and the branches are growing together creating a lovely birch-grove canopy over the bubbling rock and dry river bed.

Together, the tree canopy and fresh moving water attract plenty of birds, chipmunks and red squirrels that come in for a taste of the cool water rising up from the underground and spilling over the rock into the river rock below. I have even seen toads and snakes visiting the area.

Add solar lights for night views

At night, three solar-powered spotlights on the birch clumps allow us to enjoy our birch grove at all times, whether we are sitting outside or inside at the dining room table.

In fact, the lighted birch grove is the last thing I see every night and never fails to bring a smile to my face.

Now is the perfect time to consider creating vignettes outside your windows and doors to bring your Woodland garden into your home. I guarantee it’ll bring a smile to your face every day.

I would love to hear from you on how you were able to take advantage of existing windows and doors to create a dream view.

Take a few minutes to share your thoughts down below and inspire others to bring their Woodland indoors.

This page contains affiliate links. If you purchase a product through one of them, I will receive a commission (at no additional cost to you) I try to only endorse products I have either used, have complete confidence in, or have experience with the manufacturer. Thank you for your support.

Three spring wildflowers for the woodland garden

Spring is a magical time of year and nothing says spring more than the ephemeral wildflowers that emerge early and then disappear only to return the following spring. Here are three of my favourite.

Cultivating a love for Ephemerals

Spring ephemerals are often the first thing we think about when it comes to a woodland garden.

You know, those flowers that suddenly appear in early spring and quietly disappear almost as quickly as they appeared until re-emerging the following spring. In the meantime, they provide an essential early source of nectar for many of our pollinators and kick off the official woodland gardening season.

The diminutive Hepatica, the well-loved Trillium, and the aptly-named Bloodroot are three easy-to-grow spring wildflowers to plant in your woodland garden. All three will give you an early bloom, with the Hepatica adding lovely little hits of colour combined with its hairy stems and purple flowers.

Let’s take a closer look at all three of these woodland wonders.

(For my article on the importance of native plants, trees and shrubs, go here.)

The delicate nature of this Bloodroot flower and other spring ephemerals light up the woodland garden in early spring before they quietly disappear only to return the following spring.

Hepatica (Hepatica nobilis)

I remember going out into the woods around our home looking for the perfect Hepatica to photograph. My photo friends and I would crawl around the wet forest floor examining the delicate flowers (actually members of the buttercup family) trying to find the perfect specimen. They would emerge in early spring before the trees leafed out and when the ground was still wet from the melting winter snow. They opened only on sunny days and we would have to bring along a small mister to dampen the surrounding leaves and darken them for the photograph.

That just gives you an idea of how early you can expect these wildflowers to bloom.

Although Hepatica are native to Europe, Asia and eastern North America, our hunting grounds were the hardwood forests of southern Ontario. Theses small evergreen plants appeared, often tucked among the limestone rocks and fallen tree trunks in shades of pink, purple, blue or white sepals sitting atop the three green bracts on very hairy stems. In the United States, they are often found growing in rich woodlands from Minnesota to Maine and even as far south as Northern Florida and west to Alabama.

Spring in the woodland. Hepatica clump growing up against moss-covered limestone rock.

Hepatica nobilis is the plant found in Eastern North America, Europe and Japan, but other varieties, namely obtusa and var. acuta can also be found in North America.

There is nothing like a macro shot of a delicate, blue Hepatica with the sun streaming in from behind the flower and lighting up the delicate hairs along the stems of the plant. To get these shots we had to get low, very low. These flowers rise up only a couple of inches from the ground at best and don’t really flower unless they are getting at least some sun. Great specimens were not easy to find. Adding to the difficulty was the fact that we were capturing these images in the days of Kodachrome or Fuji Velvia with ASAs of 25 and 50.

Those days are done. Modern digital cameras open up the possibilities of capturing these wildflowers in very creative ways. And there is no real need to go into the forest to find these flowers when you can just go into your own backyard to experience them.

Hepatica hybrids have been cultivated in Japan going back to the 18th century. There are Youtube videos exploring the Japanese fascination with these flowers. This obsession is not hard to understand considering the delicate nature of the plants and how well they fit in to a Japanese-style garden. The Japanese have long perfected the hybrids with doubled petals in a range of colour patterns.

Although the hybrids can work in a woodland garden if you want a little more showiness, I always try to get the native wildflower or species plant (Hepatica nobilis)

Remember those Hepatica I photographed years ago? They were growing in alkaline limestone-derived soil. These flowers are not overly particular about where exactly they grow and can be found in a range of conditions, from the deep shade of a woodland to a grassland in full sun. They are most happy in a shaded location with rich organic soil and will live for many years. Once established, they will form colourful clumps of flowers that will bloom early in spring alongside even your crocuses. They are happy in both sandy and a clay-rich soil. What Hepatica really need for success is a covering of snow in winter and an evenly moist soil throughout the year.

Gardeners on a budget can grow Hepatica from seed, however be prepared to wait several years for the plant to bloom. Divided plants will also take a few years to recover and thicken up.

The perfect place to sit and enjoy the spring Trilliums in our front garden.

Trilliums (T. grandiflorum)

It’s hard to imagine a woodland without Trilliums. Easily recognized by their three petalled white flowers surrounded by a whorl of three green leaves, these early spring bloomers have long been a favourite of gardeners looking to celebrate spring.

Although there are more than 40 trillium species, with varying colours ranging from white to yellow, maroon and approaching nearly purple, most are familiar with the white trillium (T. grandiflorum).

Trilliums nestled in around a fallen birch branch in this natural woodland scene.

During those same photographic outings with my buddies we would often stop by the “Trillium Trail” at a local provincial park that was literally covered with thousands of Trilliums in all shapes, sizes and interesting variations. It was always an impressive site but in some ways overwhelming to photograph. So many Trilliums, so little time.

If given proper growing conditions, Trilliums are relatively easy to grow and are long-lived in our woodland gardens. Provide them with an organic-rich soil that is well drained but kept moist all summer. The flowers will bloom early before the trees are all leafed out, and become dormant by midsummer.

Trilliums do not transplant well if they are dug up from the forest floor, so always purchase Trilliums from a reputable nursery.

Gardeners on a budget can propagate Trilliums from seed, but expect to wait up to five years before you begin to see blooms. Seeds sown in the garden will not even germinate until the second year. Propagating trilliums by rhizome cuttings or, even better, division when the plant is dormant is probably an easier way to go.

A bloodroot flower tries to emerge from its leaf that wraps around it like a glove in the early spring garden.

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis)

Every spring I watch for the Bloodroot to emerge in our front woodland garden beneath the Serviceberry tree and one of our Japanese Maples. They are growing beside a large limestone boulder tucked in and among ground covers that hide the emerging plant until just before they bloom. I’m often surprised to suddenly see the lovely white blooms with the sunny yellow center.

My sudden encounters every spring is not a surprise since the Bloodroot flower emerges from the ground on a single stem wrapped up in their own single, large leaf. The white multi-petaled blossom may even begin opening before the leaf has completely unwrapped. The bloom, which can stretch upwards of 12-14 inches high, manages to rise just slightly above the leaf before opening. On a sunny day the white flower with its blood-red stem and roots, opens to reveal its stunning flower only to close up again at night.

A selective focus image of a Bloodroot flower emerging in the spring garden.

Our native bloodroots are members of the poppy family. Like other ephemerals they are only in flower for a fleeting time in spring before they disappear again only to rise up again the following spring.

Bloodroots spread rapidly and can make an excellent ground cover. And here is an interesting fact, seed dispersal is primarily done by ants.

You can expect to find them growing wild in moist woodlands throughout the U.S. and Canada from Eastern Quebec to Manitoba and south to Florida, Alabama and Texas.

For gardeners on a budget, the best method of propagation is by seed. It is best to plant the seeds immediately after you collect them, usually in early to mid-June. It’s also important to ensure the seeds do not dry out. This is a good reason to harvest your own seed rather than using commercially available stock.

More links to my articles on native plants

Why picking native wildflowers is wrong

Serviceberry the perfect native tree for the garden

The Mayapple: Native plant worth exploring

Three spring native wildflowers for the garden

A western source for native plants

Native plants source in Ontario

The Eastern columbine native plant for spring

Three native understory trees for Carolinian zone gardeners

Ecological gardening and native plants

Eastern White Pine is for the birds

Native viburnums are ideal to attract birds

The Carolinian Zone in Canada and the United States

Dogwoods for the woodland wildlife garden

Bringing Nature Home by Douglas Tellamy

A little Love for the Black-Eyed Susan

Native moss in our gardens

This page contains affiliate links. If you purchase a product through one of them, I will receive a commission (at no additional cost to you) I try to only endorse products I have either used, have complete confidence in, or have experience with the manufacturer. Thank you for your support.

Native plants help rewild his woodland garden ark

The coyote making itself at home on his back deck on his facebook page caught my eye, but the fact that Vince Fiorito brought in 50 tons of boulders and rocks into his backyard caught my attention. This guy is serious about rewilding his backyard.

Boulders build foundation for woodland garden

I thought the coyote making itself at home on Vince Fiorito’s back deck was a sign of his commitment to rewilding his backyard, but when he told me about the 40 tons of granite boulders and rocks that he squeezed into his backyard in Burlington Ont., I knew this guy was serious.

Not only is he rewilding the typical suburban-sized backyard, he is extending his efforts into the ravine behind his home and transforming it from a garbage-dumping area that is infested with invasive, non-native vegetation, into an impressive woodland ark filled with native plants and shrubs that are encouraging more fauna to set up homes in and around the area.

(Here is a link to my article on the importance of using native plants in the garden.

Maybe that explains the coyote that couldn’t help checking out his backyard and wandered up on his back deck, or the minks that came hunting squirrels in his yard this winter. Maybe it helps to explain the many small DeKay Brown snakes that call his backyard home. (See a Youtube video of his yard here.)

All you have to do is talk to Vince for a few minutes to realize this guy is serious about rewilding his yard, the ravine behind it, and the entire City of Burlington if given the chance.

Vince has even been recognized by the Hamilton/Halton Conservation Authority for his work on the Sheldon Creek watershed.

Vince Fiorito’s property backs on to a wooded area that he has worked to not only clean up, but transform with native plants into a naturalized woodland where coyotes, mink and a host of reptiles and birds call home.

It’s not the first time he has taken on the challenge. Before moving to Burlington, Vince transformed a former property in much the same way he has at his Burlington home.

More than 20 years ago in Cornwall Ont. Vince decided he could no longer live with the “McHappy” gardens that overwhelmed subdivisions all over his small town, let alone most of North America. It was then, after helping out with a school field trip to rescue trilliums and other spring ephemerals from a future gravel pit to a school yard natural habitat restoration project, that he decided it was time to take action and start cultivating native plants, with a focus on rare local species that were quickly disappearing.

“That is when I became convinced that the lawn and garden industry had created perceptions of problems where none existed (dandelions) so they could sell us solutions which are really problems,” he added.

Twenty steps to rewild your backyard

Remove all or as much grass as possible.

Stop using chemicals on your property to kill flora and fauna. Try instead to deal with problems naturally.

Replace non-native plants and trees with natives whenever and wherever possible.

Create safe habitat for animals, insects and reptiles of all kinds. This can include natural habitat from leaving snags (dead trees) to planting cedars and other evergreens that provide year-round protection. Supplement natural habitats with commercial or man-made structures such as bird houses and roosting boxes.

Consider providing natural nesting habitat for our native solitary bees as well as high-quality homes that allow for easy cleaning and removal of larvae. See my earlier article on the WeeBeeHouse.

Stop picking up leaves in the fall. Countless insects, reptiles and small mammals depend on leaf litter for winter survival. If you must, pile them into a corner or corners of your yard and let nature take care of them naturally.

Provide natural, native food sources for animals and birds from berries and nuts to flower seeds.

Ensure a safe and regular nectar supply in the yard for hummingbirds, pollinators, butterflies and bees.

Provide several sources of water in the garden, from small ponds, to on-ground bird baths that could include some form of moving water from a small solar fountain.

Consider the value of going vertical with more flowering and fruiting vines. These can also provide nesting areas for birds.

Forget a tidy garden. Nature isn’t tidy. Those spent flower stalks you are cutting down and sending to the curb, are home to insect larvae. Leave them be until late spring or early summer when the insects have had time to re-emerge.

Refrain from using gas-powered blowers on your property when a simple light raking will get the job done.

Build brush piles on your property. Even a small brush pile of sticks can be surprisingly productive. If you are having trees trimmed, ask the tree service to leave the cut branches in a pile in a corner of your property. You will save money and create invaluable habitat and hunting ground for birds and other backyard visitors.

Consider creating a hibernaculum as an overwintering area for snakes, insects, small mammals and other reptiles.

Create an open compost pile which will not only provide you with black gold, but will encourage insects and other fauna to use it as food and habitat.