Wildscape: Exploring the senses to live in peace in our gardens

Nancy Lawson, author of The Humane Gardener, explores how the senses come to life in our gardens both through our plants and wildlife.

Let natural sounds dominate our gardens

Nancy Lawson’s latest book, Wildscape, follows her highly acclaimed book The Humane Gardener building on the cornerstones of compassion and love for the fauna that make our gardens home.

If The Humane Gardener, was a plea for respect and compassion toward all species and a call for gardeners to welcome all wildlife to our backyards, Wildscape is a call to action for gardeners to recognize the problems humans are creating and how our actions are, in many cases, forcing garden wildlife to change natural behaviours to survive.

In her latest book, Wildscape (PA Press, Princeton Architectural Press, New York) Lawson explores the sensory wonders of nature and the incredible adaptations insects, mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians are sometimes forced to make to survive and prosper in our gardens.

Take a moment to check out my comprehensive review of The Humane Gardener.

Lawson’s love and compassion for wildlife comes from a lifetime of helping wildlife. As a gardener and editor with the Humane Society for many years, her extensive knowledge of the relationship between fauna and plants in the garden comes honestly.

The 284-page book explores the senses of the garden donating a chapter to each sense. Beginning with scent in the garden and moving through the remaining senses from The Soundscape, The Tastescape, the Touchscape and wrapping up with the garden Sightscape.

For more on Wildscape, check out my reviews on:

• Cultivate your own vision of beauty.

The chapters are packed not only with her own fascinating observations from a lifetime of studying her own garden, but backed with extensive scientific evidence found through her wide-ranging knowledge and research into scientific and academic studies.

The results are not always encouraging. In fact, they can be downright depressing for those of us who care about the future of the world as well as the life in our gardens, the forests and woodlands around us.

The results, however, are certainly not surprising to anyone who is paying attention.

(Rather than write a single book review, I have decided that Nancy’s work is too important to not dive fully into each chapter. We’ll begin by focusing on Chapter 2 – the one that I think most gardeners fear the most. – The Soundscape.

How excessive noise affects our garden wildlife?

If you are one of the millions of people who, like me, are almost afraid to step outside in spring, summer and fall for fear of screaming, obnoxious, gas-powered leaf blowers, lawnmowers, grass edgers and the like, this book will help put your fears and frustrations into perspective.

In short, you have plenty to fear from your neighbour’s obsessive compulsion for the perfect lawn, the perfectly manicured edges and reliance on non-native flowers, shrubs and trees.

Unfortunately, those unnecessary gas-powered machines are not only destroying your summers, they are a direct attack on the survival of birds, animals and a host of fauna that are trying to survive in our gardens.

In her book Wildscapes, Trilling Chimunks, Beckoning Blooms, Salty Butterflies and other Sensory Wonders of Nature, Lawson doesn’t just write about the annoying noises, she documents how these loud, unnatural sounds in our gardens are disturbing the natural lives, reproduction and survival of our garden inhabitants.

How wildlife use sound to communicate in our gardens

Of course, it’s not all doom and gloom.

Lawson begins the chapter pointing out how being in the garden and recognizing the chorus of songs – from the smallest peeps of tree frogs to the sexual calls of insects helps bring the garden to life. She talks about how her own lack of hearing has forced her to listen more intently.

She also points out how many animals – chipmunks for example – depend on warning calls to keep the family safe. Lawson writes about frogs and toads communicating in through vocal calls and how insects depend on sound to communicate. The importance of sound – the ability to hear and communicate with it – is of vital importance in our gardens, as is the inability to hear it because other sounds such as machinery are masking the natural sounds.

Learning to listen to our garden visitors

Lawson writes about learning to listen to these sounds.

“The bench on the edge of our pond marks a border between two worlds. In front of me is a forest in the making, where brown thrashers churn the leaves, Carolina wrens snatch moths from midair, and red-shouldered hawks perch on tulip trees, waiting for their moment. Behind me is a land bereft, a carnage of stumps where, one after the other, nesting sites for bluebirds and owls have met their doom in the yards of neighbours who expand their own houses, but declare war on leafy green homes they’ve deemed too tall or too disruptive of their acres of turf.”

Wildscape (PA Press, Princeton Architectural Press, New York) explores the Sensory Wonders of Nature in our gardens.

“Eventually they’ll call in the hitmen to take out the last of the stumps too, leaving little left for the woodpeckers who feast on insects in dead wood and sending everyone else fleeing from the deafening roar of life being ground up. Noise often begets noise, and as trees disappear, so do nature’s buffers.”

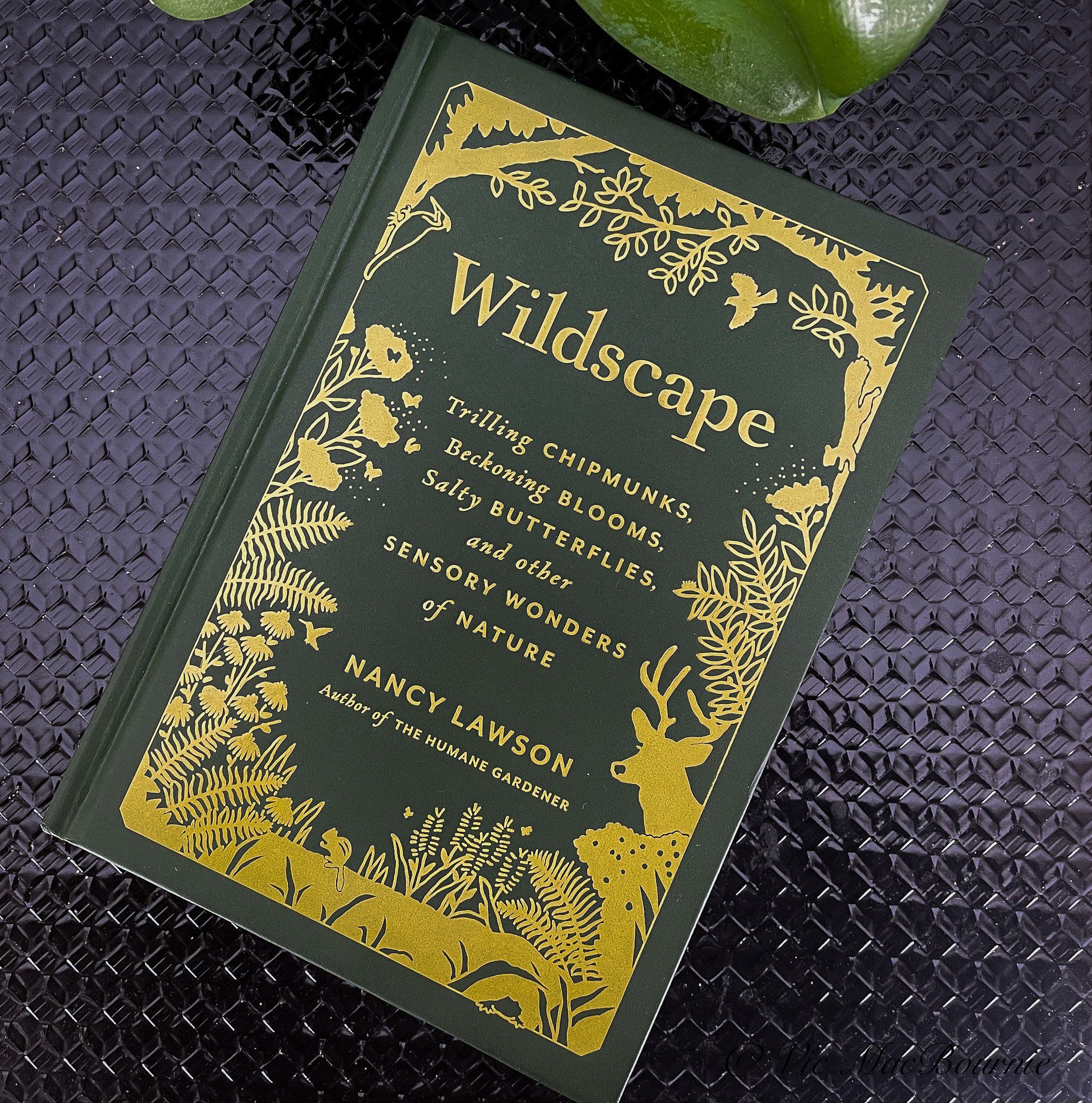

Lawson goes on to explain that as the trees are removed, the sounds from distant highways begin spread over barren backyards, void of all but the smallest of ornamental trees and shrubs. She cites a study from the University of Georgia that showed Monarch caterpillars living beside busy roads became unusually stressed to the point that these docile beings actually became extremely aggressive due to the stress caused by the noise of traffic. Once it was removed, the stress levels returned to normal.

“I’ve often wondered how animals outside can get any good shut-eye at all,” Lawson writes before going on to write about a study in Belgium that showed traffic noise has significant negative effects on European songbirds, reducing how long they sleep and prompting them to leave their nest boxes earlier in the morning.

All troubling for the future of wildlife.

Gas-powered garden tools masking natural sounds

But nothing more troubling than the constant barrage of neighbourhood noise from gas-powered mowers, blowers and trimmers.

“Like physical illness, noise falls into two general categories: chronic and episodic. Noise pollution research has typically focused on the chronic variety, partly because it’s easier to study and partly because it’s so ubiquitous; most places in the United States are less than a mile from the road. As noise from other sources grows in volume and duration, with more homeowners hiring landscaping companies that deploy large crews of mower cowboys and leaf-blowing soldiers with machines strapped to their backs, the question becomes; at what point does the episodic become chronic, adding yet another layer of aural harm?”

Images of nature help to tell the story of how the senses play an important role in our gardens.

Little to no research exists on the effects of acute landscaping noises on our wild neighbours. But as Davis notes, if the occasional passing car emitting a seventy-five-decibel sound stresses out a monarch caterpillar, ‘It really makes you think: How many other stressors, are we exposing these caterpillars to in our daily lives?’

Lawson points out that, according to global analysis, migratory birds are now avoiding noisy areas.

“But what about the animals who must stay, with no other home to go to? Though wild birds can technically fly away, that’s not an option for nesting parents who can’t leave their young. I can afford noise-cancelling headphones, which help me work while neighbours saw down trees along the road and replace them with “This is Birdland” decorative flags to celebrate the Baltimore Orioles baseball team….”

“Just as noise begets noise, the songs of birds, frogs, crickets and grasshoppers can build on themselves too, drawing more wildlife back home. Together with a smattering of neighbours who also have started to hear the call of the wild and nurture habitat for them, we will try to turn this community into a real birdland – and a land for chipmunks, spiders, bees, trees, and peace-loving people too.”

What can we do to reduce noise in our gardens?

You can’t control your neighbours’ obsessive compulsive behaviours when it comes to creating obnoxious noise throughout the neighbourhood. You can’t do too much about them starting their gas-powered mowers and snowblowers as the sun is rising. They obviously don’t care about your feelings or the problems they may be causing to local wildlife. If they are waking you up, chances are they are waking the wildlife as well.

You can, however, do everything in your power to set a good example.

Invest in electric or battery-powered garden equipment and ditch the obnoxious, outdated gas-powered equipment. Eliminate as much grass as possible so that you can easily cut your grass with a much quieter electric or battery-powered mower. I often joke that I could cut my grass at 2 am and my neighbours would never know because my battery-powered Ryobi mower is so quiet.

Check out my comprehensive post on battery-powered lawn equipment.

After seeing and hearing my mower, my thoughtful neighbour purchased a battery-powered mower, and leaf blower. Now, I have to listen intently just to hear the whirring of the electric mower. I’m still waiting for our other neighbours to follow suit.

Respecting your neighbours goes beyond the human inhabitants – it should also extend to the wildlife.

Try to be a part of the solution rather than part of the problem.

The Hidden Kingdom of Fungi opens a secret world into our forests and homes

The Hidden World of Fungi is a book for those who want to dig deep into the fascinating world of fungi in the forests, in our homes, industry and even our bodies.

A detailed, scientific approach to the study of Fungi in our forests and our homes.

The Hidden Kingdom of Fungi takes readers into a secret world and traces the intricate connections between fungi and life on earth.

Along the way, author Keith Seifert, describes how these remarkable microbes enrich our lives: from releasing carbon in plants, to transmitting information between trees in the form of mycorrhizal fungi.

This book, from Canadian publishers Greystone, takes readers of Entangled Life and The Hidden Life of Trees into the world of Fungi in its more than 200 pages backed by scientific research and the incredible knowledge of author and fellow Canadian Keith Seifert, who has spent more than 40 years studying fungi on five continents. The Ottawa, Canada resident has researched microscopic fungi from farms, forests, food and the built environment, to reduce toxins and diseases affecting plants and animals.

In the book, The Hidden Life of Trees, the authors clearly connected the communication between our forest and backyard trees with the communication highway created by the mycorrhizal fungi buried beneath the soil.

In the Hidden Kingdom of Fungi, mycologist and author Keith Seifert takes the concept to a whole other level, describing in detail the process and the interdependency.

This book is for anyone who wants to explore deeply into the world of fungi, whether it’s the obvious forms that we see growing in the forests and in our gardens to the more hidden ones that live in our homes, bodies and farms.

Mushrooms and fungi in our forests

The importance of fungi in our forests and backyard woodlands can’t be underestimated.

In fact, the author points out that fungi are critical partners in the eventual success or failure of all forests. No matter how anemic the woodlot, in the autumn you will find mushrooms growing and throwing their spores into the wind. They are most obvious in fall, but no matter what time of year you are in a forest, you are surrounded by fungi that are hidden in plain sight.

As the author points out, fungi covers the outside of leaves and bark, hide inside leaf tissue or wind their hyphae around the roots of trees. They are always at work decomposing dead pockets of wood, in the soil breaking down plants.

Are fungi part of our lives?

From our forests, to industry and into our homes, fungi play a major role in our lives and our existence.

Readers will gain knowledge into where these fungi came from and how yeast, lichens, slimes and molds evolved and adapted over millions of years. Toward the end of the book, the author explores how fungi are being used to clean up oil spills and break down plastics.

The book even touches on the role fungi is playing a role in nuclear disasters such as the Chernobyl disaster in Ukraine.

The use of fungi to clean up or detoxify spills from mining disasters, accidents or simply heavily polluted areas is call mychoremediation, and it is being used by scientists around the world. Fungal mycelium absorption capabilities have been tested to be used to clean up after forest fires, nerve gas attacks and fuel spills in land and sea.

The author points to an oil spill in 2007 in San Francisco that used a combination of human hair and oyster mushrooms to mop up the spill.

Through research into fears that Ukrainians eating wild mushrooms in and around the Chernobyl fallout zone, researchers found that many mushrooms accumulated heavy metals (such as cesium 137) in their mycelium. The research showed that mushrooms could be cultivated to extract isotopes from the soil then harvested and incinerated for disposal.

It’s just one of many fascinating ways fungi could be used to change our world into the future.

Seed to Dust: A gardener’s journey

Author Marc Hamer’s garden memoir Seed to Dust, Life, Nature and a Country Garden is an entertaining journey along a path of self discovery and garden tips. Along the way he shares his knowledge touching on important subjects ranging from the use of pesticides to allowing nature to weave its way into corners of the garden to help wildlife, birds and pollinators that inhabit it.

Finding solace in the art of gardening

Is it the gardener who breathes life into the landscape, or the garden that provides meaning and purpose to the person tending it?

It’s a question many of us have contemplated while we work our own gardens, and it’s the underlying question that author Marc Hamer explores throughout Seed to Dust, Life, Nature and a Country Garden, his latest novel detailing a year in his life as the lone gardener of a 12-acre private garden in the Welsh countryside.

Seed to Dust is another outstanding book from Canadian publishers Greystone Books, publishers of Peter Wohlleben’s NYT bestseller The Hidden Life of Trees and follow-up book The Heartbeat of Trees.

Seed to Dust follows Hamer’s successful book How to Catch a Mole, described in the Wall Street Journal as a “quirky and well-received 2019 memoir” and “account of how Mr. Hamer, a pacifist, came to retire from catching moles, since getting them out of a garden usually meant killing them.”

Hamer’s 400-page Seed to Dust memoir begins in January exploring – one month at a time in easy-to-digest chapters – a full year in the life of the professional gardener as he maintains the estate of his mysterious and wealthy employer, affectionately nicknamed Miss Cashmere.

“Anyone who loves the earth knows that a tidy-mindedness is death for nature. I am a wildflower, and untidy weed.”

Seed to Dust is the perfect book to curl up with a good coffee on a winter’s afternoon remembering what soon awaits us in spring.

Over the course of the year, he reflects on his life and that of Miss Cashmere’s since he began working for her: her husband’s death, the departure of her children from the stately home where she now lives alone.

It’s the reflections, however, on the difficulties he has faced – homelessness, loneliness, hunger, extreme poverty – that gives the readers great insight into his approach to gardening and the natural world.

Much more than a monthly how-to garden calendar, Seed to Dust tells the story of a young man finding his way in a world that sees him as somewhat of an outcast, struggling through depression, thoughts of suicide, self-discovery and, finally, as an older man ready to retire from working the land, content with his lot in life and the world he has built for himself, his wife and grown children.

Let nature guide your way

This is a tale for all garden lovers. It’s particularly valuable for those gardeners who struggle to let nature guide them in their journey. It’s for the gardener who is looking to get closer to nature, and for the gardener struggling to find meaning in the trees, plants and wildlife.

It’s a book I found both inspiring and very personal. Hamer and I – being of a similar age – share many of the same garden and life views, and struggle with similar health ailments as we try to complete everyday garden chores.

The book, which has been shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing, is for those searching as much for gardening advice as they are searching for answers to some of life’s most complex questions.

His is, what he himself admits, a simple life; one that is reflected in his approach to life, nature and the art of gardening. In his garden there are no “special” plants, just common flowers, shrubs and trees that, when put together in just the right way, create a beautiful vignette or natural landscape.

““I do not spray the aphids on my roses, although in the past I have lost whole crops of broad beans to them. I am nurturing sparrows and ladybirds, beetles, ants and underground fungus instead.””

He writes early in the memoir about the garden he maintains for his employer Miss Cashmere: “This is not my garden, but it’s not hers, either. Just paying for something doesn’t make it yours. Nothing is ever yours. People who work with the earth and the people who think they own bits of it see the world in totally different ways.”

We can all benefit from a garden’s healing powers

“Any garden belongs to people who see it – it is like a book, and everybody who visits it will find different things.”

This theme of self discovery in the garden guides his belief that we all benefit from the healing powers a garden brings.

Later, he writes about how his gardening style changed. Over time, the garden evolved from the formality that once dominated the 12-acre site. Flowers are allowed to wander to create their own natural drifts – some even creeping into the once manicured lawns – giving the garden a naturalistic feel and welcoming pollinators, wildlife and critters that inhabit the garden’s wild areas.

He speaks of the hidden corners where he feels more at home among the grasses and overgrown plants.

“The way I choose to shape this or that space; wild, or tight and neat, closed or open. … If it were left alone for a few months, nature’s fertile beast would take over and it would become something else entirely. There are places where I let that happen, hidden from the house, where things grow wild and nature thrives. Damp spots for ferns and rotting wood, fungus and beetles, and hideaways for hedgehogs.”

It’s not difficult to see his respect for living things in the garden, and there is little question that his life experiences have helped shape his garden style.

“We were all deliberately sown with seeds of fear and hatred, but I chose not to water mine. I leave those seeds in arid ground: the racist, xenophobic, sexist, homophobic beliefs that I grew up surrounded by. I will not give them my attention, will not allow them to take root in me.”

No room for chemicals in the garden

His life experiences also reflect his views about the use of chemicals in the garden.

“There are chemicals available to spray lawns with, so that it shouldn’t grow so quickly; others to kill the worms and beetles so there are no worm casts, no moles feeding on them. … These are for the people who are not gardeners, people who want to control nature.”

“To speak of controlling nature is like the waves wanting to control the sea, the song singing the thrush, the flower creating the earth. We are not the sea, we are not the thrush, we are not the earth. We are the wave, the song, the flower.”

Man’s maddening machines of destruction

Hamer has harsh words about the machinery of gardening.

“I work around the buildings with the brush-cutter. It screams and makes smoke, a senseless thing that slashes back the grasses and native wildflowers. A ‘weed’ is a word that tidy-minded use for plants they do not want.”

“Anyone who loves the earth knows that a tidy-mindedness is death for nature. I am a wildflower, and untidy weed,” he writes.

“The scent of petrol, engine fumes, hot oil and blended greenery fill the air, and behind me the meadow is flourishing. The machine is violent and stupid. The violent and stupid nearly always win; it’s why they are created: to fight and win for their owner’s gain.”

His message to all gardeners, but especially Woodland and Wildlife gardeners is straight forward and one we would do well to heed: “I do not spray the aphids on my roses, although in the past I have lost whole crops of broad beans to them. I am nurturing sparrows and ladybirds, beetles, ants and underground fungus instead.”

Seed to Dust: Life, Nature and a Country Garden is published by Greystone Books. I encourage readers to check out this Canadian publisher who has made publishing Naturally Great Books its focus. The impressive list of nature-inspired books including The Hidden Life of Trees and The Heartbeat of Trees puts them in a class all their own for nature lovers. You can check out their catalogue here.

Feeling the Heartbeat of (woodland) Trees

The importance of a single tree outside your door, to the increasing threat to our ancient forests and woodlands is explored in Peter Wohlleben’s newest book The Heartbeat of Trees, Embracing our Ancient Bond with Forests and Nature. The followup to his award-winning book The Hidden Life of Trees is a must read for woodland gardeners and anyone who cares about the environment and the future.

Can a tree improve our health?

Can a single tree in your backyard or even a city-owned tree in the front yard make a difference in your life, in your health, in the health of your family?

Most of us tree lovers would say, ‘yes’. But do we really know, or are we simply using our belief systems to justify our desire for more trees?

Sleep easy my friends, there is evidence that a single tree in your front yard, even if it is a lonely “city tree” can make a difference – a big difference.

In his book, The Heartbeat of Trees, Embracing our Ancient Bond with Forests and Nature, author Peter Wohlleben cites a large-scale study conducted in Toronto, Canada by scientists at the University of Chicago that showed a single tree planted by a front door improves health and well-being.

Scientists apparently gathered data from about 30,000 Toronto residents – and from about 530,000 trees the city had already mapped.

The results are certainly eye opening.

The Heartbeat of Trees follows up on the success of The Hidden Life of Trees.

The study found that “ten more trees in a residential neighbourhood improved the health of the residents as much as an increase of $10,000 in income a year ( including the improved medical care that comes with such an increase.)”

Wohlleben adds that this is not just about mental health.

If you are interested in this book or other gardening books be sure to check out the impressive selection at Alibris (link).

“The liklihood of heart and circulatory diseases, the leading cause of death in North America these days, dropped measurably. Eleven more trees in the neighbourhood was an improvement in cardio-metabolic health equivalent to an additional $20,000 a year or, measured another way, it reduced a person’s biological age by 1.4 years.”

This is just one of the gems found in this New York Times best-selling author’s follow-up to The Hidden Life of Trees, a book that not only revealed to the world the incredible importance of trees in our climate-threatened world, but was also made into a critically acclaimed movie by the same name. Go here, to check out my earlier article on this ground-breaking book.

(Dr. Nadina Galle has taken her inpspiration from The Hidden Life of Trees and The Heartbeat of Trees and used it as a building block in her groundbreaking work to use smart technology to monitor the health of the urban forest. Read about her outstanding work here in my recent article The Internet of Nature.)

Pocket Forests are an intriguing approach to creating miniature forests. Check out my post on creating a mini-forest.

A forest prospers as a family group

The author is quick to point out, however, that although a single tree is a great thing, a forest is much better.

The Hidden Life of Trees was clear about the benefits of forests over singular trees planted on a front yard surrounded by non-native grass and facing the world – the beating sun, the cold winds, freezing temperatures – on their own. He compares the “street trees” that are found in most urban environments, to “street kids.” These lone trees face difficult and almost always shortened lives compared to trees that share resources as a family group in a proper forest or woodland.

The new book places more of the human element into the equation.

Wohlleben is convinced that ancient ties linking humans to the forest remain alive and intact. The test so many of us face is whether we are able, in an era of cell phone addiction and ever-expanding cities, to allow ourselves to rediscover nature, to reconnect with the forest and feel its heartbeat once again.

Whether we feel this connection or not, he points out with scientific evidence how our blood pressure stabilizes near trees and how the colour green calms us, while, the forest, especially at night sharpens our senses.

The 264-page book published this past June by Greystone Books is the perfect follow up to The Hidden Life of Trees, a book that introduced the world to a form of communication between a family of trees in the forest and their connection to the “Mother Tree.”

His new work takes another step into the forest and introduces readers to a host of revelations about our relationship with trees, forests and especially those who are left to care for the earth’s remaining trees.

“The Heartbeat of Trees reveals the profound interactions humans can have with nature, exploring the language of the forest, the consciousness of plants, and the eroding boundary between flora and fauna,” the book’s promotional material states. "The author “shares how to see, feel, smell, hear, and even taste your journey into the woods.”

“Above all, he reveals a wondrous cosmos where humans are a part of nature, and where conservation is not just about saving trees – it’s about saving ourselves, too.”

Forest bathing: Is it a new trend?

Nowhere is this more evident than his chapter on “Forest bathing.”

I doubt this is a new term to readers, but if it is, the act of forest bathing involves submersing yourself into the quiet, soothing sounds, smells and spirit of a natural forest.

Today, in Japan, a doctor can write a prescription for their patient that includes a “walk in the woods – a sick note, as it were, that gives you permission to spend time in the forest.”

This trend in natural medicine is making its way to Western medicine in the form of forest bathing.

For my comprehensive post on Forest Bathing, please go here.

Wohlleben points out that “with the longing for natural spaces forest bathing has spilled out of Asia, Called shinrin-yoku in Japanese, the whole thing sounds like ancient wisdom. However, it isn’t at all. Quite the opposite is true, in fact. Japanese forest agencies came up with the idea and the name in 1982 as a way to make people more aware of the health benefits of the country’s forests.

According to Dr. Qing Li of the Nippon Medical School in Tokyo, Japan, Forest Bathing is simple. In is 300-page book published on the subject, he explains how it works.

Turns out it is very simple. “Choose a forest you like (it could even be in a city park) and you go there to relax,” Wohlleben explains.

“Then you gather all your senses and dive into all the smells, sounds and sensations. According to Li, all you need to do is accept the forest’s invitation to slow down. Mother Nature takes care of the rest.”

Although he admits some skepticism over the whole “forest bathing” phenomena, he tells the story of a family walk in the forest. After some time resting and talking after a long walk in the wood he maanges, the author remembers how he and his family slowly began to relax as they enjoyed their company and the sights sounds and smells of the forest to the point where they were more relaxed than they ever could be at home.

It’s a relaxed state only the forest can help us achieve and one that takes us back to our ancient roots.

The Heartbeat of Trees is, by no means, all about natural remedies and how we can discover ourselves in the depths of ancient forests.

Ancient forests are under threat

In the final chapters Wohlleben warns readers about the threats our natural forest face and the efforts by small groups to save these critical remaining old-growth (or at least important) forests.

Unfortunately, these challenges are world wide.

He talks about his experience hiking up to a tiny ancient spruce tree names “Tjikko” that has lived for 9,550 years in a national park in Sweden. He talks about his fears for its future amid tourists trying to capture selfies with the highly threatened piece of natural history that for so many is nothing but an opportunity to stumble around it and its ancient roots for nothing more than a quick selfie for social media.

He tells the story of the Kwiakah First Nation in British Columbia, Canada that is fighting to save its forest in The Great Bear Rainforest from the timber industry. Clear cutting is threatening their traditional hunting and fishing grounds, not to mention the unique ecosystem that Mother Nature has created.

Of course, Canada is not alone. He tells of similar stories in Germany, throughout Europe where old-growth forests are non-existant and on the border of Poland and Belarus where an important forest (the Bialowieza) of oaks, lindens, hornbeams, maples and spruce is being threatened.

Wohlleben’s conclusion leaves plenty of room for optimism for our future and the future of our children.

He concludes: “… people have sown the seeds of hope across generations so that now a complete change in direction is being ushered in. A change that is taking place in not in our minds but in our hearts.”

Words well spoken, but I prefer to leave the last word with Richard Louv, author of “Our Wild Calling and The Last Child in the Woods. (See my earlier article on why children need more nature in their lives)

“As human beings, we’re desperate to feel that we’re not alone in the universe. And yet we are surrounded by an ongoing conversation that we can sense if, as Peter Wohlleben so movingly prescribes, we listen to the heartbeat of all life.”

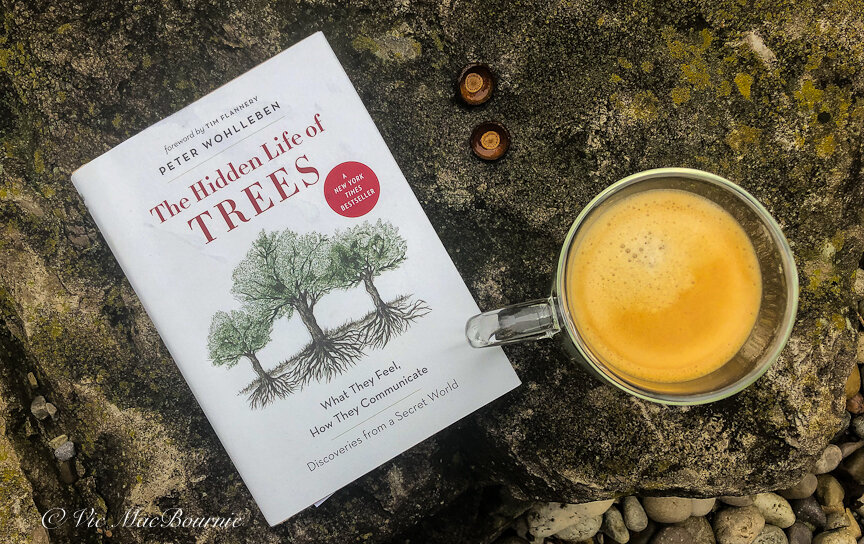

How trees communicate in our woodland gardens: The Hidden Life of Trees

The Hidden Life of Trees is a New York Times bestseller every Woodland Gardener needs to read. Author Peter Wohlleben explores how trees communicate in nature and how they struggle in urban environments calling them “street kids” and explaining the difficulties they face in our woodland gardens and on urban environments.

Do trees work together to help one another?

If you love trees – and I know every woodland gardener does – then you need to get The Hidden Life of TREES. (Amazon Link)

Peter Wohlleben’s 288-page, New York Times best seller will open up a new world for Woodland gardeners looking for answers about what is really going on in their backyards, local woodlots and ancient forests.

There is a reason this book has sold more than 2 million copies. Canadian publisher Greystone Books unleashed the book in its 8th printing on September, 2016 in the First English Language Edition, and has never looked back. (A fully illustrated coffee-table version is also available, see below.)

Not convinced about the importance of this book, consider that it has also been made into a movie. Check out this YouTube link for a taste of The Hidden Life of Trees movie version. (It will be available on AppleTV starting the month of October.)

It should come as no surprise to any of us that several backyard trees work together to create their own environment – from cooling our yards with shade to creating their own fertilization and micro environments at ground level.

Sit back and relax with a good coffee and The Hidden Life of Trees. The New York Times best seller is a must for Woodland gardeners.

What will come as a surprise to most of us, however, is the incredible goings on under our feet – from just a few inches beneath the soil to the depths many of our mighty tree roots reach. Beneath the soil there’s a communication highway where battles are waged, where life and death struggles play out through the seasons, and where families of trees come together through the “Mother Tree” and work together, sometimes over centuries, to survive, and ensure the health and prosperity of the woodland.

If you are looking to purchase the Hidden Life of Trees, or any other gardening book for that matter, be sure to check out the outstanding selection and prices at alibris books.

Armed with this knowledge, woodland gardeners can begin to make sense of so many questions about our gardens; its forest canopies, why a variety of tree is not flourishing and how we can help our woodland thrive.

(Dr. Nadina Galle has taken her inspiration from The Hidden Life of Trees and The Heartbeat of Trees and used it as a building block in her groundbreaking work to use smart technology to monitor the health of the urban forest. Read about her outstanding work here in my recent article The Internet of Nature.)

But this is not a how-to book. There are no pictures of trees. There are no outright tips for how to plant trees, where to plant them or when to plant them.

The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate is a book that explores the often mysterious lives of individual trees, of forests, of trees left alone to fend for themselves in urban areas, on our streets and in our backyards. This is a book, written by a German forester, about how trees have communicated with one another over decades and even centuries, how they work together to save their own against disease, natural disasters, man’s destructive habits and the invaders we have brought that threaten the very existence of our native trees. Underlying it all, is the affect climate change is having and will continue to have on our woodlands, our urban forests and ancient rainforests.

“Life as a forester became exciting once again. Every day in the forest was a day of discovery. This led me to unusual ways of managing the forest. When you know that trees experience pain and have memories and that tree parents live together with their children, then you can no longer just chop them down and disrupt their lives with large machines.”

Trees work

Will a single tree thrive in my yard?

The author makes it clear from the beginning that the lone tree in the middle of our front and back yards surrounded by grass that is so prevalent in many urban homes, is not an ideal situation for a tree’s prosperity.

“A tree is not a forest. On its own, a tree cannot establish a consistent local climate. It is at the mercy of wind and weather. But together, many trees create an ecosystem that moderates extremes of heat and cold, stores a great deal of water, and generates a great deal of humidity. And in this protected environment, trees can live to be very old. To get to this point, the community must remain intact no matter what. If every tree was looking out for only itself, then quite of few of them would never reach old age.”

The above quote may well explain why our urban trees rarely reach maturity, let alone old age. Where I live, this is clearly evident in local birch trees. In the heart or our urban communities these trees rarely survive into maturity. In the older, more rural areas where trees are less crowded and are given more room to grow, Birch trees seem to do much better. In my yard, I have planted three clumps quite close to one another and they seem extremely happy, possibly beginning to communicate with one another.

As trees struggle on their own, some would die opening up the forest floor to sunlight, the author explains. “The heat of summer would reach the forest floor and dry it out. Every tree would suffer.”

Do trees help one another survive?

If we conclude that every tree is valuable to the forest community and worth keeping around, it should come as no surprise that, as Wohlleben writes, “…even sick individuals are supported and nourished until they recover.”

He compares them to a herd of elephants. “like the herd, they, too look after their own, and they help their sick and weak back up onto their feet. They are even reluctant to abandon their own.”

If you have never thought about trees in this way, you may be shocked about how deep Wohlleben goes to explain just how extensively trees communicate through primarily – but not limited to – underground networks.

For the doubters, let me just say that his arguments and scientific data are hard to ignore.

Five key takeaways from this book

• Trees are much more complicated than most of us realize and their means of communication are complex and sophisticated.

• The importance of planting a grouping (possibly an island or a grove if possible) of the same variety of native trees is much more beneficial than planting individual specimens, especially if they are non-native trees.

• Recognizing that a tree’s needs must be met not just after initial planting but long into their growth cycle is important, and reducing physical barriers can be critically important.

• Single trees planted in our yards are more on their own than we might realize, and it matters that they cannot communicate easily with other trees. Best to take extra care of these lone trees.

• A woodland garden thrives not only because it is more natural than say a cottage garden, but because trees work together to create a positive environment that helps to guarantee success even when they are threatened.

Can trees communicate?

Consider that four decades ago, scientists noticed an interesting phenomenon on the African savannah.

They noted that giraffes feeding on acacia trees moved on quickly to other trees. The same scientists discovered that mere minutes after the giraffes began feeding on the trees, the acacias began pumping toxic substances into their leaves to ward off the large herbivores. The giraffes moved on, walked past a number of nearby acacias, before resuming their feeding on a group of trees about 100 yards away.

“The reason for this behavior is astonishing. The acacia trees that were being eaten gave off a warning gas that signaled to neighbouring trees of the same species that a crisis was at hand. Right away, all the forewarned trees also pumped toxins into their leaves to prepare themselves…. The giraffes were wise to this game and therefore moved farther away … to a part of the savannah where they could find trees that were oblivious to what was going on.”

The entire book is filled with fascinating stories about how trees’ self defences are used to ward off fungal diseases, beetle attacks and even how they deal with woodpeckers and other potentially destructive mammals that depend on trees for their own survival.

This is just an example of the many ways trees may communicate in a natural environment. The book goes on to explain a myriad of ways trees communicate, but in doing so, it also explores the many ways communication between trees is cut off leaving orphaned trees alone and fending for themselves.

Communication between trees growing in managed forests and in many of our urban parks is often restricted and underdeveloped for a variety of reasons explored in the book.

How are single trees like “street kids”?

But it’s the chapters on street kids that many gardeners and homeowners will likely focus on the most.

A drive down a suburban street or through a large city reveals just how many trees are left alone to fend for themselves.

In his book, Wohlleben describes these orphaned trees as “street kids.”

“Urban trees are the street kids of the forest. And some are growing in locations that make the name an even better fit – right on the street. The first few decades of their lives are similar to their colleagues in the park. They are pampered and primped. Sometimes they even have their own personal irrigation lines and customized watering schedules.”

The problem comes when these trees decide it’s time to go out and establish themselves. They quickly meet with hard, unlivable soil and even concrete walkways, roads that don’t allow any water to penetrate down into the hard soil compacted by machinery

“When trees are planted in these restrictive spaces, conflicts are inevitable….The culprit is sentenced to death.”

It is cut down and another planted in its place, but the new one is planted in a built-in root cage to restrict its roots from ever causing damage to the surrounding hardscaping.

Sound familiar?

What problems does a single tree face?

The difficulties “street kids” face does not end there. In large urban areas, where the lights never go out, these trees never get a chance to rest. They need a period of rest to thrive. Often, the concrete traps heat and even winters, another time for the tree to rest, are non-existant.

The sun, too, heats the concrete and black asphalt to the point of killing any living organism in the soil beneath it, depriving the “street kids” of water and nourishment.

In large urban areas these problems are obvious, but take a look around at your own trees and consider if they are facing some of these same problems.

Are the roots of the tree in your front yard growing under the road? Would additional watering help it survive hot, dry periods?

Is your favourite dogwood struggling because it is now in bright sunlight most of the day after a neighbour cut down a large maple exposing it to harsh sunlight? Maybe we need to add a large shade tree nearby to reduce the amount of sunlight hitting the dogwood.

Is your concrete driveway cutting off all water to your favourite roadside maple tree? Maybe it’s time to do what I did and replace the old asphalt or concrete with stone or permeable brick to allow water to seep down into the roots of the tree. Not only will it help the tree, it also reduced the amount of toxic runoff from your driveway into the sewer systems by keeping more water on your property.

As I said earlier: this is not a how-to book, but it certainly provides food for thought about how we can help our own little forest survive and thrive in our woodland garden.

About the Author: Peter Wohlleben spent over twenty years working for the forestry commission in Germany before leaving to put his ideas of ecology into practice. He now runs an environmentally-friendly woodland in Germany, where he is working for the return of primeval forests. He is the author of numerous books about the natural world including The Hidden Life of Trees, The Inner Lives of Animals, and The Secret Wisdom of Nature, which together make up his bestselling The Mysteries of Nature Series. He has also written numerous books for children including Can You Hear the Trees Talking? and Peter and the Tree Children.

If you like the Hidden Life of Trees, be sure to check out its sequel The Heartbeat of Trees recently published.

How to attract Native Bees to your wildlife garden

It’s time our 4,000 native bee species took centre stage rather than playing second fiddle to European honey bees. In her book Our Native Bees, Paige Embry puts native bees in the spotlight where they belong.

Creating a lawn for native bees: Time to rethink normal

The value of our native bees can’t be underestimated, but every day, every year, every growing season they play second fiddle to those “other” bees.

Their role in the natural world could not be any more clear than their importance to native plants.

(For my article on the important role of native plants, go here.)

In a world where insects and other creepy crawlies get a bad rap, solitary bees are the Rodney Dangerfield of the Bee world.

They certainly don’t deserve that disrespect.

Our Native Bees is a stunningly beautiful book that explores the importance of North America’s endangered pollinators. it is pictured here with a WeeBeeHouse native bee home.

Considering the work native solitary bees do for us, they should actually be celebrated as one of the most important contributors to the natural world and a vital part of our agricultural economy.

Why don’t they get the respect they deserve?

Paige Embry, author of the Our Native Bees book is a true solitary bee aficionado. “It annoys her — rightly — that most people know next to nothing about the 4,000 species of native bees nesting in the ground, in trees and in the sides of our houses,” points out the New York Times, in a review of her book.

“The hardest part of getting a bee lawn into use isn’t developing the seed mix; it’s dealing with people’s vision of what a lawn should be…If we didn’t have to worry about our neighbours, I think there would be a much more diverse look.”

Count me among those who knew “next to nothing about the 4,000 species of native bees.”

I never really gave bees much thought even though the solitary native bees are regulars in our backyard.

After reading her book (Published by nature and garden book publishers Timber Press in 2018) and my own research, I still consider myself a novice when it comes to native bees. There is so much to learn, but Embry’s book is a good beginning for anyone wanting to explore the world of native solitary bees.

Our Native Bees: North America’s Endangered Pollinators and the Fight to Save Them is clear and concise, mixed with entertaining stories and anecdotes about author Embry’s journey into discovering North American native bees from her childhood to present day. The book is by no means a dry, complex, scientific or academic approach to protecting and attracting native bees.

It’s their story and she tells the troubled tale with the novice native bee lover in mind.

“Native bees are the poor stepchildren of the bee world,” she writes in the introduction of the book. Honey bees get all the press – the books, the movie deals – and they aren’t even from around here, coming over from Europe with the early colonists.”

She goes on to point out that in 2015 the U.S. federal government “issued a plan to restore 7 million acres of land for pollinators and more than double the research budget for them.”

Sounds great, where’s this disrespect you talk about?

The disrespect came in the name of the new program: the “National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators.”

As Embry aptly points out: “Four thousand species of native bees, not to mention certain birds, bats, flies, wasps, beetles, moths, and butterflies, reduced to ‘other pollinators.’ ”

It’s the sad tale of our native bees. But with the efforts of Embry, bee researchers and entrepreneurial dreamers who are working hard to help our native bees get the respect and recognition they deserve, there is certainly some reason to be optimistic for the 4,000 species of native bee that call North America home.

No-one is kidding themselves, however, the story of their survival is still being written and there is no guarantee it will have a fairy-tale ending.

Let’s make this clear from the beginning, Embry has nothing against honey bees.

“They dance and make honey and can be carted around by the thousands in convenient boxes, but from a pollination point of view, they aren’t super-bees. On cool, cloudy days when honey bees are home shivering in their hives, many of our native bees are out working over the flowers. Bumble bees do their special buzz pollination of tomatoes, blueberries, and various wild species…. The trusty orchard mason bees are such hard-working yet slovenly little pollen collectors that several hundred can pollinate an acre of apples that requires thousands of honey bees.”

Embry asks: “Where are the book and movie deals for these bees?”

Where indeed?

Our Native Bees book, however, is a good beginning.

The little black, 195-page gem of a book is actually written in two halves: The first half focuses on the commercial importance of native bees in the agricultural world and tells the story behind California’s massive almond industry among others; the second half explores the importance of the native bees in nature and efforts made to save them including an unlikely pairing between the future of native bees and intensive work being done at a U.S. golf course to create ideal habitat for them and other pollinators.

The Power of Bees

In her final chapter of Our Native Bees, Embry writes about the power of these extremely docile native bees. Here are a few excerpts from that chapter:

Bees have power: They have the obvious power of pollination and supplying us with many of our favourite foods. they also have an unexpected superpower – the ability to form connections and build community among people. … People come together to volunteer at bee labs or help with bee surveys. Some use vacation time to take bee classes and hunt for bees.

Bees are reselient: If we just stop kicking the bees quite so hard, we can help them – and see the results immediately. Renounce pesticides. Plant flowers that bees in your area like. Be a little slovenly in the garden; leave some old broken stems and a little bare dirt show. The bees will come.

Bees are diverse: Most people think of honey bees when they hear the word bee or, even worse, they envision a yellow jacket or some other kinds of wasp. Twenty thousand species rife with differences being reduced to either a very unusual outlier of the group or something that is not a member of the group at all.

In the first half of her book, Embry sets up the difference between imported honey bees and our native bees.

For a complete novice, when it comes to the importance of bees and their role in agriculture, I have to admit that the information Embry provided was both enlightening and fascinating.

Embry’s love affair with bees and her subsequent book actually had its roots with the the tomatoes of her Georgia childhood.

“The summertime table in my house always had a plate of sliced tomatoes on it. … When I grew up and moved away, I too, grew tomatoes…, she writes in the book.

“Some pollination happens as a result of wind just shaking the plants, but more and bigger tomatoes result with the help of bees. Not just any bee can do it, though. It wasn’t until I was nearly fifty that I learned that honey bees can’t produce those tasty red and orange globes. Tomatoes require a special kind of pollination called buzz pollination, where a bee holds onto a flower and vibrates certain muscles that shake the pollen right out of the plant.”

“If the idea of flowers growing in the grassy lawn just isn’t quite achievable yet, there’s always the golf course route. Take out some of that lawn and convert it into a home and dining hall for bees. It’s all a matter of rethinking normal.”

So, it turns out that bumble bees and other native bees are the keys to tomato pollination.

Embry goes on to devote an entire chapter to the question: “Did Greenhouse Tomatoes Kill the Last Franklin’s Bumble Bee?”

You’ll have to read the book to get the answer to that question, but it raises a concern about big agriculture and the future of our native bees.

Native versus naturalized bees

In case you were wondering what’s the difference between Native and Naturalized bees, Embry explains it in the following way: “The North American bee is one that evolved right here. The honey bees we know are not native because they came over from Europe with the early colonists. Some of those early bees escaped into the wild (they went feral), where they did quite well. Those feral bees are considered naturalized, not native.”

Native Bees’ economic value

Like many of us, I had not given much thought to how fruit and nuts get to our table and the importance of pollination to that end.

Little did I know that the pollination of massive orchards and fields were so dependent on bees and that non-native honey bees were the key pollinators. All this despite the fact our native bees are more efficient, harder workers and free for the taking if only we could figure out a way of attracting them to acres and acres of endless orchards and agricultural fields.

It should not come as a surprise that the story of our bees, both honey and native bees, are rooted in the agriculture industry and the bees’ future could very well depend on that same industry for good or bad.

Much has been written lately about the future of bees and other pollinators and how their numbers are being threatened by pesticides.

But enough of that. The agricultural story and the work being done behind the scenes is a fascinating part of the native bee story. The fact that Canadians, more specifically New Brusnwick, played a key role in their story, and not in a good way, furthers my interest in the plight of these fascinating little bees.

Native Bees’ value in our gardens

It’s in our gardens, however, where our focus lies.

Native bees have quickly become a favourite of concerned homeowners many of whom are taking actions in an attempt to save them. Even if it’s nothing more than putting up small bee habitats on their properties where the solitary bees can safely procreate and live their lives. (For my post on WeeBeeHouse native bee habitats see below)

Gardener’s Supply Company, in Burlington, Vermont also offers an impressive native bee house for readers looking to begin provding a home for native bees. Their page also includes an interesting video of the bee house in action. To view it, click here.

Best five things I learned from Our Native Bees

1) There are at least 4,000 species of native bees in North America in every shape, size and colour you can imagine.

2) Sweat bees – beautiful green iridescent native bees – get their name because some like to lick up sweat

3) Most native bees are small, live alone and do not sting either because they have no stingers or are so docile that it would take a life and death situation to get them to sting.

4) Native bees vary in size from the mighty carpenter bee (about an inch in length) to the tiny Holeopasites calliopsidis that isn’t much bigger than Roosevelt’s nose on a dime. And it’s not even the smallest native bee in the United States. That honour goes to Perdita Minima.

5) There are 20,000 species of bees worldwide that are responsible for the seeds of rebirth of three-quarters of the flowering plants in the world.

Bees in the Grass: Rethinking Normal

We all have to take a serious look at the acres of grass that dominate our urban and rural neighbourhoods. (For my post on removing lawns see below.)

Embry wastes little time advocating for a change in the way homeowners see their carpets of monoculture they call grass. She uses an example that is both shocking and encouraging.

She turns her focus to golf courses and goes into great detail about two programs at American golf courses that encourage setting aside natural areas on the golf course for native pollinators.

The first program stems from a 2002 report from the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation who teamed up with the U.S. Golf Association to write a report called “Making room for Native Pollinators: How to create Habitat for Pollinator Insects on Golf Courses.”

The second program, and one she turns her attention to, is a program out of Europe, Operation Pollinator, started by Syngenta, one of the world’s largest agrochemical comanies (another name for a pesticide company).

The program started in the United Kingdom in the early 2000s after a survey of golfers revealed that what they liked most about going out for a round of golf was the nature they sometimes stumbled across in the more natural areas of the course. That, together with the desire to reduce the costs of operating a course, lead to the unexpected marriage between nature and a massive pesticide company.

By creating a natural area for pollinators, the pesticide company was able to use their expert biologists to turn perfect turf into pollinator-friendly areas. The plan cut down on the cost of pesticide while at the same time providing more nature for the golfers.

“Operation Pollinator for golf courses came to the United States in 2012, and by 2016 more than 200 golf courses in twenty-nine states had an Operation Pollinator plot. The plots range from half an acre to more than a hundred.”

To say the program has been a smashing success for native bees is a huge understatement.

This program, of course, brings us to our own lawns and gardens.

Embry asks: “What golf courses are doing with Operation Pollinator is going a step beyond just adding some flowers to the grass. They are removing turf in areas that don’t need to be grass and replacing it with flowers for pollinators. That’s one approach, and it works in some places. Sometimes, though, you want a lawn to be a lawn , a place for play, picnics, and soccer pitches. What if a lawn can be all that and a place for pollinators too?”

She goes on to talk about incorporating more clover, and the thirty-seven bee species found on clover in grass in a Minneapolis study.

This simple addition to turf allows for the soccer pitches, while still providing some native bee habitat.

From the simple addition of clover into the lawn Embry moves on to the “making of a bee lawn.”

The transformation from golf-course turf to the perfect bee lawn has been the focus of many studies and creations that has met with varied success over the years.

As one researcher at the University of Minnesota explains: “the hardest part of getting a bee lawn into use isn’t developing the seed mix; it’s dealing with people’s vision of what a lawn should be…"

“If we didn’t have to worry about our neighbours, I think there would be a much more diverse look.”

Embry goes on to explain as a possible solution: “If the idea of flowers growing in the grassy lawn just isn’t quite achievable yet, there’s always the golf course route. Take out some of that lawn and convert it into a home and dining hall for bees. It’s all a matter of rethinking normal.”

Yes, Ms Embry, it certainly is.

Thanks for shedding some light on our native bees.

As an affiliate marketer with Amazon or other marketing companies, I earn money from qualifying purchases.